Cambodia’s top government officials threatened arrests and dispatched a heavy police presence around the country this week to head off protests against the Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Triangle Development Area, or CLV.

The economic cooperation deal between the three countries was forged in 1999 and officially established in 2004.

But last month, Senate President Hun Sen – the country’s former longtime ruler – ordered the arrests of three activists who criticized the agreement in an 11-minute video on Facebook that has sparked a backlash from senior government leaders.

Last weekend, Cambodian overseas workers in South Korea, Japan, Canada and Australia held protests, voicing concerns that the CLV could cause Cambodia to lose territory and natural resources to Vietnam.

This touched a nerve. On Monday, Hun Sen again warned of more arrests, and on Tuesday, Minister of Justice Koeut Rith said those who participate in anti-CLV protests could face treason charges and potential prison sentences of between 15 and 30 years.

Activists have set up a Telegram chat group to coordinate a Aug. 18 demonstration in Phnom Penh. In response, the Ministry of Interior has sent police, military police, soldiers, bodyguards and special forces to provincial capitals and has set up checkpoints on highways.

So how did an 11-minute video posted to social media in July turn into an apparently delicate security situation in just a few weeks?

What is the CLV?

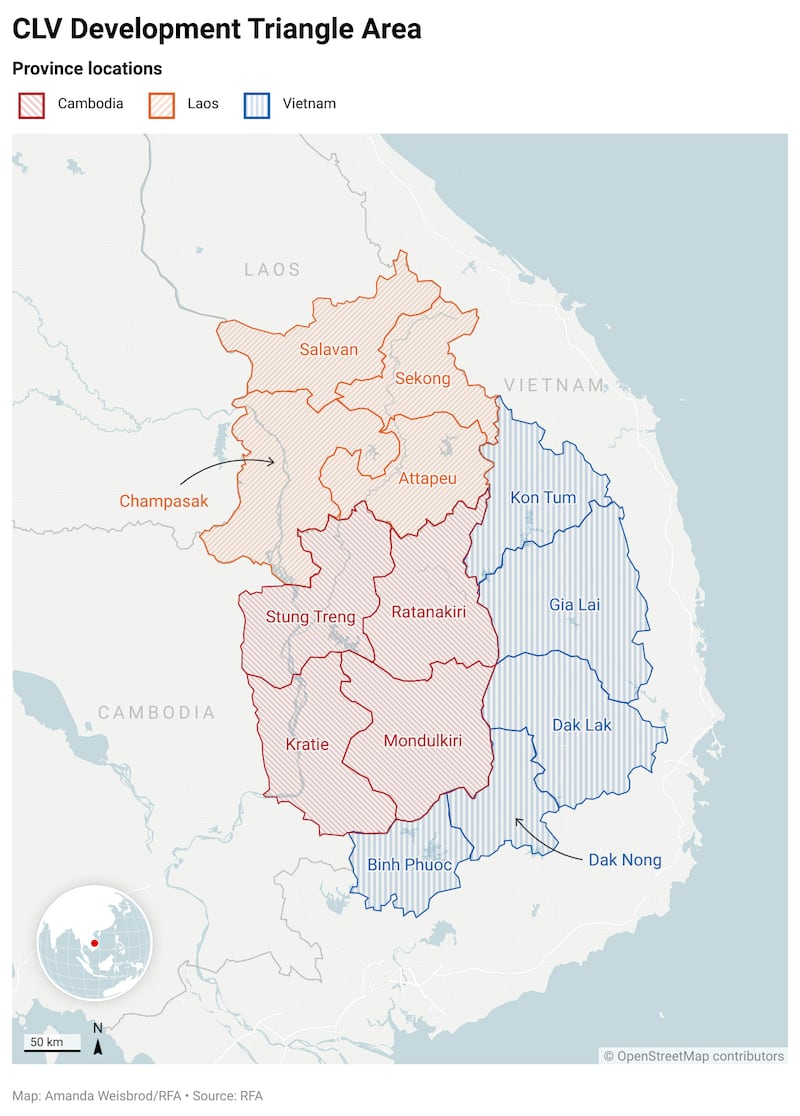

The three-nation CLV is aimed at encouraging economic development and trade between five border provinces in Vietnam, four neighboring provinces in Laos and Cambodia’s four northeastern provinces – Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri, Kratie and Stung Treng.

The agreement allows for the free flow of citizens who live in these provinces into the other two countries for trade and investment.

Given the Cambodian government’s lax approach to immigration and its reputation for corruption, some Cambodians are worried that multi-decade agricultural land concessions to Vietnamese or Lao investors will result in a loss of control of large pieces of Cambodian land.

The CLV "is a cover for further illegal deforestation, land evictions and exploitation of natural resources for foreign gain," exiled opposition leader Mu Sochua wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter, on Tuesday.

"Continued illegal Vietnamese immigration into the four Cambodian provinces concerned by the agreement, and the effective control that Vietnam will wield over the economy of the region, means that the provinces will effectively become vassals controlled by Vietnam," she wrote under the Khmer Movement for Democracy account.

Hun Sen, his son Prime Minister Hun Manet and other top ministers have said publicly that Cambodia would not lose territory to Vietnam under the CLV.

National Police spokesman Chhay Kim Khoeun told Cambodian media outlets that 10 people were arrested this week after they made critical comments about the CLV.

“Recently, there is a small group that wants to destroy the country through fake news to topple the legitimate government,” Interior Minister Sar Sokha wrote on Facebook on Friday. “I would like to remind the small group … to wake up and withdraw themselves from the small group who are inciting you from overseas.”

Why is the CLV generating protests now?

The three activists arrested on July 23 have been holding workshops on Cambodia’s 1991 Paris Peace Agreement, which formally ended decades of civil war. The workshops are part of efforts to educate Cambodians about the development of parliamentary democracy in the country.

In the 11-minute Facebook video, the three activists – Srun Srorn, Peng Sophea and San Sith – spoke about the general concerns Cambodians have about the CLV.

In response, an angry Hun Sen announced in a televised speech that he had ordered the arrests of the activists. He warned against making comments about the potential loss of Cambodian territorial integrity to Vietnam – a sensitive political issue that has led to the arrests of numerous opposition activists over the years.

Additionally, Hun Manet said on Aug. 2 that Cambodians should be careful of protesting against the government, citing Bangladesh's recent demonstrations in its capital that caused that country's leader to resign and flee the country.

“I don’t want to see this type of situation happening in Cambodia,” he said. “Especially in Phnom Penh.”

The arrests of the three activists have angered some young Cambodians, who have watched as the government has neutralized independent media outlets and most of the political opposition since 2017.

Is the plan for a new canal contributing to this?

Another factor is the Aug. 5 launching ceremony for the construction of the US$1.7 billion Funan Techo canal, which will link Cambodia's capital, Phnom Penh, and the Gulf of Thailand.

The Cambodian government sees the project as an opportunity to become less dependent on Vietnam as shipments could bypass Vietnam’s Mekong delta. Vietnam has repeatedly asked for more information on the environmental impact of the 180-kilometer (112-mile) canal.

“While the government is trying to promote the Funan Techo canal, the CLV issue has distracted the attention and support from the people for the canal,” political commentator Seng Sary told Radio Free Asia.

“But generally, Hun Sen is good at exploiting situations and when he saw people rising up against the CLV, he used that as an excuse to take action against remaining political opposition activists, social critics and non-governmental organizations.”

What historical factors are at play?

Many Cambodians consider Vietnam an “historic enemy” and often mention the loss of territory known as Kampuchea Krom – a region in the lower Mekong Delta that comprises much of present-day southern Vietnam.

Additionally, Hun Sen and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party have historical ties to Vietnam’s Communist Party. Hun Sen first became a government minister shortly after a Vietnam-led invasion drove Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge from power in 1979. He stepped down as prime minister last year to pave the way for the appointment of his eldest son, Hun Manet, to the position.

Recently, the government has done a poor job of explaining to Cambodians about the CLV, according to Seng Sary.

“It seems to have made this issue into a dark mystery for the people,” he said. “The recent arrests have only deepened doubts and concerns.”

Hun Sen’s attempts to shut down debate on the CLV “reflect his authoritarian paranoia” and his public requests to the courts on the recent arrests “make it crystal clear that the judiciary has no independence and simply operates as a weapon at the disposal of the government,” Mu Sochua wrote on X.

RFA was unable to reach Chhay Kim Khoeun and government spokesman Pen Bona for comment on Friday.

Translated by Sum Sok Ry, Keo Sovannarith and Yun Samean. Edited by Matt Reed.