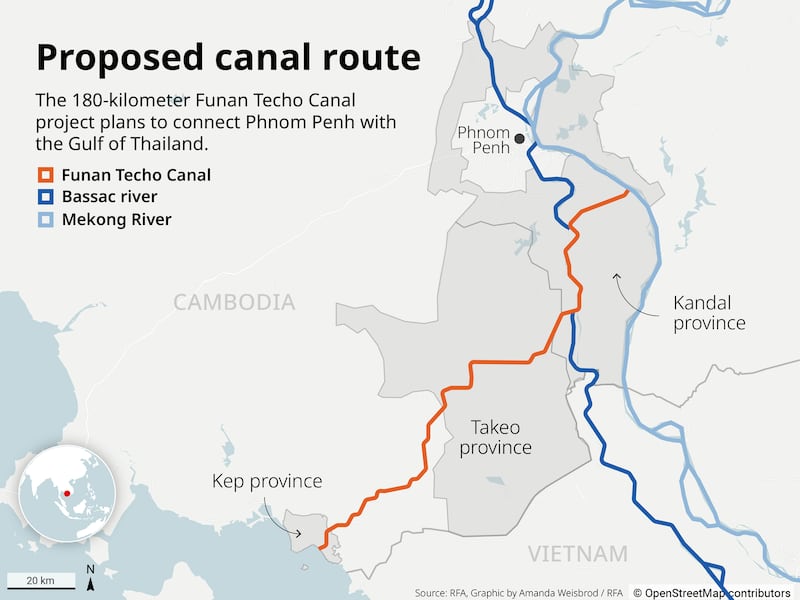

Cambodia’s plan to build a canal linking its capital to the coast to end dependence on Vietnamese ports has raised a barrage of questions about its economic viability and environmental impact.

In the second part of the report, RFA examines the possible impact of the planned Funan Techo canal on the Vietnam-Cambodia relationship.

Veteran Cambodian leader Hun Sen and his son, Prime Minister Hun Manet, have waged a campaign to rally support for the Funan Techo canal project that they say embodies the spirit of the Cambodian nation and has stirred a surge of national pride.

But it has also exposed some underlying cracks between neighbors Vietnam and Cambodia, whose fates have been intertwined since the earliest days of their history, particularly since Vietnam defeated Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge in early 1979.

Between the 1st and 6th centuries, Angkor Borei, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) south of Phnom Penh, was the capital of Funan – a kingdom that covered parts of what are now Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia.

Adopting the ancient kingdom’s name for the Funan Techo canal invokes a Khmer culture and prosperity that, during its heyday, was far superior to that of its neighbors.

‘Their land, their rules’

Just 10 minutes by boat from the modern Angkor Borei, in the middle of a swamp, is a tiny settlement of about 10 simple dwellings of Vietnamese fishing folk. One of them, Nguyen Chi Cuong, hails from An Giang province less than 10 kilometers (six miles) away over the border in Vietnam.

Cuong said he had heard of the canal but didn’t know much about it.

“I was told we may have to pack up and go back to An Giang, leaving this area for the canal construction, but we’re not sure when,” the man said. “This is Cambodia: their land, their rules. We can’t do anything but comply.”

“We’re thankful enough they let us stay here to fish, the Cambodians treat us very kindly and we can go back and forth without any problem,” Cuong added.

But away from the relaxed border, the Funan Techo canal has stirred the sort of animosity between Cambodia and Vietnam that has not been seen in years, with China looking likely to be the main beneficiary of the strife.

Vietnam complained about a lack of information from Cambodia about the US$1.7 billion canal, which will link Cambodia’s capital to planned ports on its coast and end dependence on Vietnamese ports to the south.

The Vietnamese foreign ministry repeatedly urged Cambodia to provide an impact assessment on water flows and ecological balance of the Mekong River delta. Cambodian officials responded in an uncharacteristically offhand way, saying they didn’t have to.

They said that Cambodia was only required to notify the Mekong River Commission – a four-country intergovernmental organization in charge of jointly managing the river – as the project does not connect directly to the Mekong but to the Bassac River, which is considered by Cambodian planners a tributary rather than the mainstream of the Mekong.

The Bassac branches off the Mekong just south of Phnom Penh and then meanders south, alongside the Mekong, into the delta and the South China Sea. The canal will link the Mekong to the Bassac, then run from the Bassac west to the Cambodian coast.

Cambodia insists the canal will not reduce the flow of the Mekong into Vietnam’s main rice-growing delta region and the impact downstream will be negligible.

The Washington-based Stimson Center, in a report on the canal, rejected the Cambodian position, saying the project’s designation of the affected stretch of river should be changed from “tributary” to “mainstream” in order to initiate a consultation process mandated for mainstream projects.

‘Ambitious plan’

Vietnamese scientists disagree about the extent of disruption the canal may cause to the Mekong’s flow.

Some, like Le Anh Tuan from Can Tho University, reckon the flow could be reduced by as much as 50% during the dry season.

Others, like independent specialist To Van Truong, say Tuan’s estimate is “overblown” and give a much lower estimate of just 4%.

One thing they seem to agree on is the need for more consultation and information to protect the delta, home to 17.4 million people and already suffering from saltwater incursions.

While the media has focused largely on the environmental impact and financial viability of the project, Vietnamese analysts weigh the geopolitical ramifications, especially in light of China’s looming presence over the region.

Cambodia’s Deputy Prime Minister Sun Chanthol met Zheng Shanjie, a high-ranking official in charge of development policies, in Beijing on Sept. 9 to discuss Chinese projects in the kingdom, including the Funan Techo canal, and “ensure their timely completion,” the Khmer Times reported.

State-owned China Road and Bridge Corporation is one of the main investors in the canal.

RELATED STORIES

[ Will Cambodia’s Funan Techo canal be a success?Opens in new window ]

[ Developer of Cambodian canal comes with baggage Opens in new window ]

[ Cambodia’s Hun Dynasty stakes reputation on Funan Techo canal Opens in new window ]

Nguyen Minh Quang, a lecturer at Can Tho University, said that the canal was aimed at transforming southern Cambodia, where China already has military interests, both economically and strategically.

“Early evidence reveals that the Funan Techo canal is only phase one of an ambitious plan,” the Vietnamese lecturer said in a recent analysis that he co-authored.

“Urbanization, agricultural modernization, mining activities, and infrastructure investment, including the construction of a deep seaport in Kep, will follow the canal, which will likely make way for Chinese-backed economic enclaves and military logistic supporting nodes in southern Cambodia.”

The analyst argues that if those development hubs were to be realized, it would give the Chinese navy perfect access at the Ream naval base, nearby in Cambodia’s Sihanoukville province, to localized military supply chains and resources.

“This, in turn, would essentially translate as a unique advance for China’s alleged de facto military outpost in the Gulf of Thailand,” Quang added.

Nationalist sentiments

Most coverage of the canal in Vietnam’s media has been factual, reflecting the official, measured call for information and transparency.

The picture is quite different in Vietnam’s social media sphere, however, where patriots in May launched barbs at Hun Sen on his TikTok posts with a blizzard of rude comments.

“Vietnam sacrificed its blood for peace in Cambodia,” one social media user said, referring to a Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in late 1978 to oust the notorious Khmer Rouge and install a breakaway faction of the Cambodian communist party that included Hun Sen.

Vietnam forces remained in Cambodia for the next decade, battling the Khmer Rouge and other guerrillas and securing the foundations of a Cambodian administration that remains in charge today.

“Don’t forget tens of thousands of Vietnamese volunteers who were killed in Cambodia,” read another social media post, reflecting Vietnamese anger about the way Hun Sen dismissed Vietnamese concerns about his pet project.

“Ungrateful,” “China’s puppet,” and “traitor” were among the terms Vietnam’s social media critics leveled at Hun Sen.

Relations between Vietnam and Cambodia can become politically charged, especially in Cambodia where a legacy of resentment over perceived injustices and conquests can be whipped up, at times into violence.

Cambodia’s political parties have all used the anti-Vietnam card to bolster legitimacy and support, and Hun Sen is particularly vulnerable to such politicking as he rose through the ranks of a government installed by Vietnam, analysts say.

Vietnam and the Phnom Penh government were implacable foes of China through the 1980s but that has changed radically.

In 2015, the Cambodian foreign ministry sent stern diplomatic notes calling on Vietnam to halt all encroachment in disputed areas between the two countries.

Now Hun Sen and his ruling Cambodian People’s Party are unwavering Chinese allies and the canal controversy has revealed a surprisingly hard line on Vietnam.

In almost unprecedented criticism of his old ally, Hun Sen, responding to Vietnam’s questioning of the canal, said in a speech in April that Vietnam was “building a lot of dams to protect their crops and these have an impact on Cambodia.”

Cambodia was “not inferior to Vietnam,” he said. “Cambodia knows how to protect its interests, Vietnam doesn’t need to care.”

‘Cambodia’s responsibility’

Older folk on the Vietnamese side of the border remember the war that forged ties between the neighbors along a river that has bound their fates.

“We share one river, of course we care,” said farmer Le Van An, 63, in Vietnam’s An Giang province. “It’s Cambodia’s responsibility to let us know what they will be doing.”

The former soldier said a reduced flow of water would be disastrous.

“I hope the Vietnamese party and government will prevent that from happening,” he said.

In Ba Chuc village, a memorial stands as a reminder of the horror of nearly 50 years ago when Khmer Rouge forces attacked deep into Vietnam in 1978 massacring more than 3,000 villagers.

An, who fought in theVietnam-Cambodia border war triggered by the massacre, said he held no grudge against Cambodians.

“They’re just like us,” he said, though adding that he didn’t trust the Cambodian government.

“Especially now that it has China’s backing.”

Edited by Taejun Kang.