Authorities in Cambodia are using the coronavirus to carry out “arbitrary arrests” of opposition supporters and government critics, Human Rights Watch (HRW) said Wednesday, noting that at least 30 people have been detained for spreading “fake news” and other offenses since the start of the pandemic.

In a statement, the New York-based rights group urged Cambodia’s government to “immediately and unconditionally drop the charges against all those accused of crimes in violation of their rights to freedom of expression and association.”

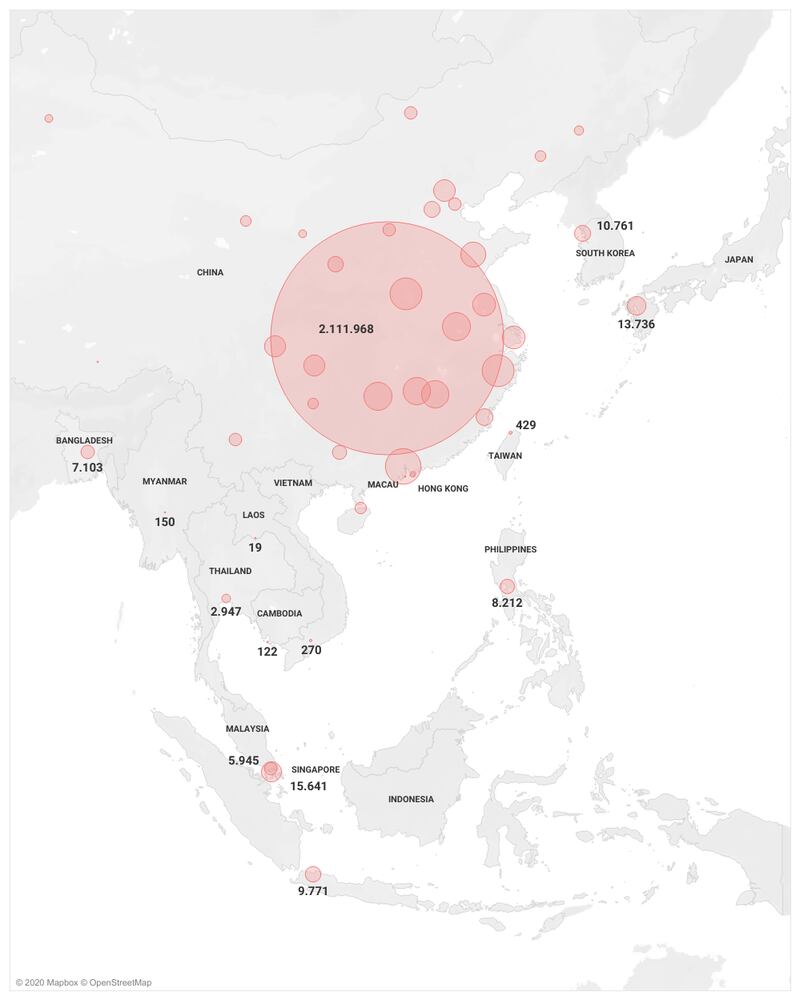

While the number of cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, has held steady at 122 with no deaths for more than two weeks, Cambodia’s one-party parliament recently approved legislation authorizing a state of emergency to contain the spread of the virus that observers have warned could be used to unnecessarily increase already heavy restrictions on freedoms of expression, association and peaceful assembly.

Acting head of state and Senate president Say Chhum signed the “Law on Governing the Country in a State of Emergency” into effect on Wednesday on behalf of King Norodom Sihamoni, who is undergoing an annual medical exam in Beijing.

“Prime Minister Hun Sen is busy tightening his grip on power and throwing political opposition figures and critics in jail while the world is distracted by COVID-19,” said Phil Robertson, HRW’s deputy Asia director.

“Peaceful political activity and criticizing the government are not crimes, including during a pandemic. The authorities should drop the bogus charges and release those detained.”

HRW said it had documented 30 arbitrary arrests between late January and April 2020, including a dozen people with ties to the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which was banned by the Supreme Court in November 2017 for its role in an alleged plot to topple the government.

The ban on the political opposition, along with a wider crackdown by Hun Sen on NGOs and the independent media, paved the way for his ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) to win all 125 seats in parliament in the country’s July 2018 general election.

According to HRW, fourteen people remain in pretrial detention on what it called “baseless charges,” including incitement, conspiracy, incitement of military personnel to disobedience, and spreading false information or “fake news.”

Among those arrested in addition to the opposition activists was a journalist quoting a speech by Hun Sen, and ordinary Cambodians who criticized the government’s response to the outbreak.

Using the virus

Meanwhile, HRW noted that the absence of recent cases in Cambodia “raises concerns that either the government is not testing for the coronavirus or that medical workers fear reprisal for reporting results.”

The group said provisions in the state of emergency law that raise particular rights concerns include possible indefinite renewals of the state of emergency, the wide scope of unfettered martial powers granted to the executive without independent oversight, and unqualified restrictions on civil rights that allow for arbitrary surveillance of private communications and silencing of independent media outlets.

HRW’s assessment of the law came weeks after Rhona Smith, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia, warned of its “broadly worded language” and said that a “state of emergency should be guided by human rights principles and should not, in any circumstances, be an excuse to quash dissent or disproportionately and negatively impact any other group.”

HRW noted Wednesday that while international human rights laws allow for restrictions of some rights in the context of serious public health threats, “they must have a legal basis, and be strictly necessary, based on scientific evidence and neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application, of limited duration, respectful of human dignity, subject to review, and proportionate to achieve the objective.”

It cited a group of United Nations human rights experts who on March 16 said that “emergency declarations based on the COVID-19 outbreak should not be used as a basis to target particular groups, minorities, or individuals. It should not function as a cover for repressive action under the guise of protecting health ... and should not be used simply to quash dissent.”

“The state of emergency law will be a disaster for the human rights of the Cambodian people, who face having their civil and political rights stripped away,” Robertson said.

“Foreign governments and donors should demand the Cambodian government prioritize public health at a time of crisis rather than further repressing basic rights.”

Cambodian Ministry of Justice spokesman Chhin Malin could not be reached for comment in response to HRW’s statement on Wednesday but had previously told RFA’s Khmer Service that the government will not be able to carry out arbitrary arrests if a state of emergency is enacted.

Instead, he said at the time, the law will be used to target anyone who seeks to “provoke chaos” in Cambodia while such a state is in effect.

“The government isn’t targeting the opposition party or dissidents—we will implement the law against those who breach the law,” he said.

Reported by RFA’s Khmer Service. Translated by Samean Yun. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.