Updated at 11:35 am EST on 2021-09-29

Newly minted alliances among nations in the Indo-Pacific region have sidelined ASEAN, analysts say, with some arguing that the 10-nation grouping of Southeast Asian countries dug its own grave through its inaction on regional issues.

Within a span of just seven months, two Washington-led Asia-Pacific groupings – one ideological and one military – have quietly circumvented the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in a bid to blunt China’s growing dominance and militarization in the South China Sea.

ASEAN has for long touted its “centrality” to the region, and powers such as the United States, China, and Russia have described it as the anchor of the Indo-Pacific security landscape, but such words are starting to ring hollow, said James Chin, a professor at Tasmania University.

“[W]ith the Quad and AUKUS, they clearly bypassed ASEAN. They pay lip service to ASEAN, but they don’t really care what ASEAN thinks,” Chin told BenarNews, an RFA-affiliated online news service.

AUKUS is the new security alliance under which the U.S. and the United Kingdom will provide Australia the technology needed to build nuclear-powered submarines.

It was preceded by the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), whose members – the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia – said at the group’s first summit in March that they are committed to an open, secure, and coercion-free Indo-Pacific region.

The White House statement on AUKUS and a statement subsequently issued by Australia’s ambassador to the regional bloc both nodded to ASEAN, but little else.

And ASEAN is to blame for that, Chin said, an opinion echoed by other analysts.

“ASEAN itself is the cause of its own problem. The fact that it cannot resolve the South China Sea issue, can’t even get China to agree to the Code of Conduct after 20 years, can’t solve the Myanmar problem… It shows that ASEAN can’t be taken seriously based on its historical track record,” Chin argued.

For nearly two decades, China and ASEAN have been negotiating a Code of Conduct, to lay out guidelines for how nations with competing claims in the South China Sea must behave. In 2019 ASEAN agreed with China to finalize the code in three years, but there is no sign a COC will be ready by next year.

After the Feb. 1 military coup in Myanmar, ASEAN struggled to come to a consensus on how to deal with its member state. The bloc’s nations in late April finally agreed to send an emissary to help resolve the post-coup crisis there, but it took ASEAN more than 100 days to name a special envoy. That envoy has not yet secured permission from the Burmese junta to talk to all stakeholders.

Meanwhile, amid mounting violence against civilians in Myanmar, ASEAN successfully lobbied to block a U.N. call to suspend arms sales to the Burmese military, in the wake of the coup.

Jeremy Maxie, an associate at Strategika Group Asia Pacific, a security consultancy in New Zealand, noted that ASEAN is often a hindrance in resolving regional issues.

“ASEAN has proven over the last several years that it is irrelevant, even counterproductive, in responding to regional security issues from Myanmar to SCS,” Maxie said on Twitter.

Some ASEAN members may complain about AUKUS, but it is a lesson for the regional bloc, noted former Indonesian Foreign Minister Marty Natalegawa.

It is a reminder of "the cost of its dithering and indecision on the complex and fast-evolving geopolitical environment," Natalegawa told The Jakarta Post.

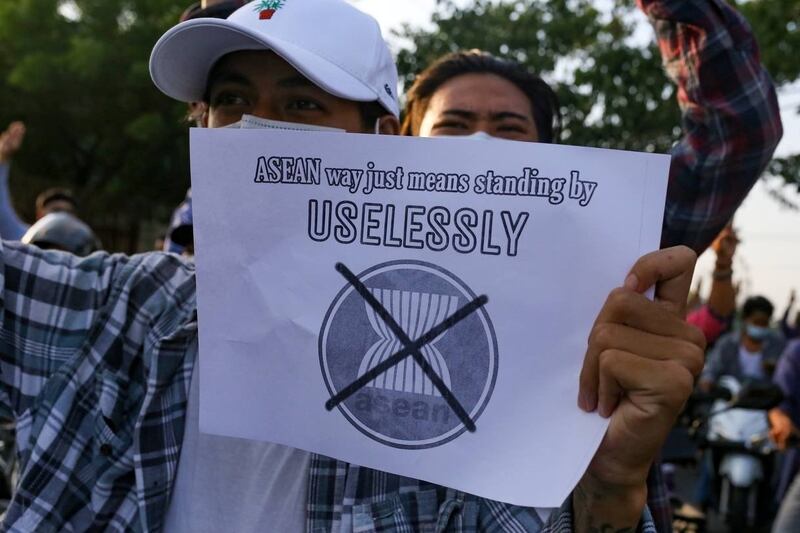

A protester against Myanmar's junta holds a placard criticizing the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), in Mandalay, Myanmar, June 5, 2021. [Reuters]

‘Picking up the slack’

Meanwhile, Derek J. Grossman, a senior defense analyst at U.S. think tank Rand Corporation, said ASEAN members should not have been surprised an alliance such as AUKUS was formed.

“[O]ne has to genuinely ask: what did ASEAN expect if it couldn’t [or] wouldn’t act vs China’s growing military threats? Someone has to pick up their slack,” Grossman said on Twitter.

The governments of Southeast Asia face a dilemma in responding to China’s assertion of its sweeping claims in the South China Sea, in large part because of their economic dependence on Beijing.

Regional analyst Oh Ei Sun told BenarNews last week that Malaysia preferred to maintain a working strategic relationship with Beijing, “despite China’s frequent incursions into what Malaysia considers to be its territorial waters” in the South China Sea.

Moreover, to the shock of the country’s opposition parties, Defense Minister Hishammuddin Hussein said he would seek China’s views on AUKUS on a trip to Beijing.

It was “a little embarrassing for Malaysia to so publicly subcontract its foreign policy,” noted John Blaxland, professor at the Australian National University.

Indonesia, meanwhile, recently downplayed the lingering presence of a Chinese survey ship working in Jakarta's exclusive economic zone – even after warning Chinese fishing boats and their Coast Guard escorts to get out of the Natuna Sea on multiple occasions.

China claims nearly the entire South China Sea, including waters within the EEZs of Taiwan, and of ASEAN members Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. While Indonesia does not regard itself as party to the South China Sea dispute, Beijing claims historic rights to parts of that sea overlapping Indonesia’s EEZ as well.

Beijing has repeatedly rejected a 2016 international arbitral award that declared China’s claim over most of the South China Sea baseless.

United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken sits next to Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi during a meeting with foreign ministers of ASEAN member countries on the sidelines of the 76th Session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York, Sept. 23, 2021. [Reuters]

‘A polarized situation’

Though it famously operates by consensus, there is no common stance among ASEAN nations on AUKUS, notes Rizal Sukma, a senior researcher at the Jakarta-based Centre for Strategic and International, who is a former Indonesian ambassador to Britain.

“Some are supportive, like Singapore, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Some are opposed like Malaysia and there are those who are concerned including Indonesia. Others remain silent, such as Brunei and Laos,” he told BenarNews.

“But, the question is really, does ASEAN have the capacity to be a place where great powers’ interests can be managed? I doubt it. ASEAN has even become more irrelevant.”

Still, Rizal said, the three AUKUS countries should recognize that the region’s nations are worried about the escalation of tensions in Southeast Asia.

“The issue is not AUKUS, but the U.S.-China rivalry, which is the driving force for AUKUS cooperation and for the consolidation of the PRC’s military position in the South China Sea,” he said.

“It is better for ASEAN to focus on how to manage the rivalry if it wants to remain relevant,” Rizal said.

Former Malaysian deputy defense minister Liew Chin Tong concurred that there is still a role for ASEAN in the current geopolitical landscape – if it can step up.

“I would like to see some of the ASEAN member states – seeing the danger of a polarized situation – come together to find a strong common position to hold back the great powers,” Liew told BenarNews.

ASEAN needs to be more dynamic, and AUKUS may well push it to be so, Nick Bisley, professor of International Relations at LaTrobe University in Australia, noted on Twitter.

“ASEAN never works as well as when it feels its centrality is at risk.”

Reported by BenarNews, an RFA-affiliated online news service.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story identified Hishammuddin Hussein as Malaysia's Foreign Minister. He is Defense Minister.