The South China Sea is likely to remain one of the thorniest issues between China and ASEAN as they mark 30 years of ties and struggle to negotiate a long-planned code of conduct for the disputed waterway, analysts say.

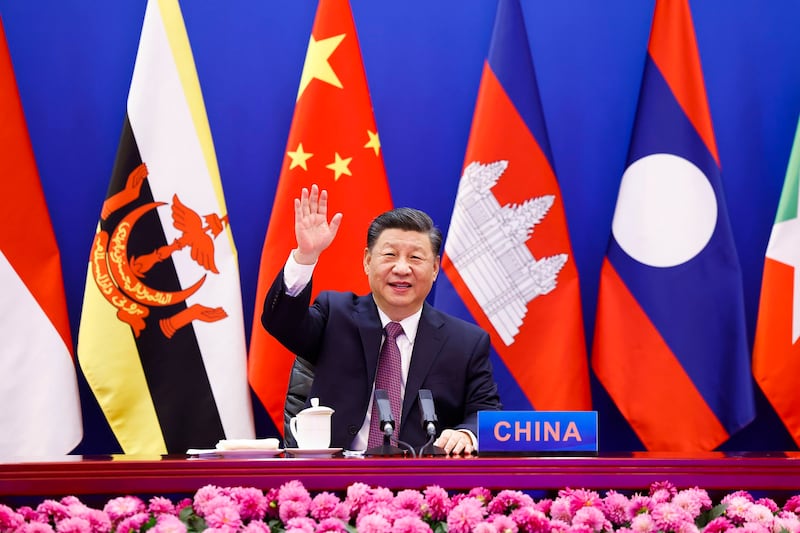

The leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and China held a virtual summit Monday to mark the three-decade anniversary. They also declared a comprehensive strategic partnership.

But despite reassurances from President Xi Jinping that China will always be a good neighbor and friend of ASEAN, and would never seek hegemony nor take advantage of its size to “bully” smaller countries, maritime disputes were lurking in the background.

In a rare public rebuke of China, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, expressed abhorrence and “grave concern” Monday about last week’s firing of water cannon by Chinese coast guard ships on Filipino supply boats in the South China Sea.

The U.S. and the European Union have also condemned the Chinese actions, which Washington called “dangerous, provocative and unjustified.”

China’s diplomats are believed to be making fresh efforts to speed up negotiations with ASEAN on the Code of Conduct (COC) that is intended to reduce the risk of conflict in the South China Sea, analysts say.

But they question whether the resulting code will have teeth, and say there are major stumbling blocks in the way.

Tran Cong Truc, former chief of the Vietnamese government’s Border Committee, said one obstacle is the “nine-dash line” that China uses to demarcate its sweeping claims. The other is China’s reluctance to address the interests and rights that outside parties have in the South China Sea -- other than China and ASEAN -- in accordance with the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

“I don’t think these obstacles are likely to be removed any time soon,” Truc said.

Long and winding road

China claims historical rights to almost 90 percent of the South China Sea, an area roughly demarcated by the nine-dash line. Other claimants have rejected those claims and a 2016 international arbitration tribunal ruled that they had no legal basis.

Claimants include ASEAN members Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The other members of the bloc are Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Singapore and Thailand.

China and ASEAN agreed on a Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea in 2003, but progress on a COC has been slow going, even after a draft agreement was released in 2018.

One reason that China may have for optimism in reaching an agreement in the coming year is that close ally Cambodia will hold ASEAN’s chairmanship in 2022.

“The process of concluding the COC in the South China Sea is progressing well. There seems to be less problems in the negotiation process so far,” said Sovinda Po, a research fellow at the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace.

He said that rather than risk reputational damage by siding with China, Cambodia was “likely to strike the middle ground that could both keep China happy and gain trust from its ASEAN fellows.”

Other regional analysts are less sanguine.

“If the idea is to produce a comprehensive COC that addresses all of the different concerns of the claimant countries, I do not think it is achievable,” said Jay Batongbacal, director of the Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at the University of the Philippines.

“The differences are still too wide at this point, and they have yet to begin really substantive discussions on the key provisions, each of which are probably going to be difficult to reconcile between 11 parties,” he said.

Carlyle Thayer, emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales in Canberra, Australia, pointed out that there’s still a long and winding road ahead and it is unlikely that the final draft of the COC could be achieved soon.

“The draft COC which was adopted in August 2018 is supposed to go through three readings. At present only negotiations on the second reading are underway,” he said.

“The Single Draft Negotiating Text is nineteen A4-sized pages in length. So far there has been provisional agreement on the Preamble which is one page and nine lines of text,” Thayer said.

“Negotiations are now focused on the Objectives section under General Provisions. The Preamble and Objectives are low hanging fruit because they are not controversial but the next section, Basic Undertakings, is very complicated,” he added.

Third parties’ involvement

The current draft text doesn’t clearly define the COC's legal status as a binding treaty nor contain a binding dispute settlement mechanism.

“A general political document like that is seen by countries like Vietnam as less desirable,” said Tran Cong Truc.

Truc added that “without those technical details any statements and promises would only be empty slogans designed for political purposes.”

The draft COC also makes no mention of third parties who may wish to accede to it.

“China wants to avoid involvement of other parties including the U.S. in the South China Sea. It is in China's interest to keep the dispute solely between China and ASEAN claimants,” said Aristyo Rizka Darmawan, lecturer in International Law at the Center for Sustainable Ocean Policy, University of Indonesia.

“It is not surprising for China to push the COC negotiation considering what happened in the last few months including the introduction of AUKUS (the trilateral security pact between Australia, the U.K. and the U.S.),” Darmawan told RFA.

“There are several important issues that ASEAN and China have to deal with in the COC though,” he warned, adding that “it is important that the fundamental legal issues are considered and parties should not rush it through.”