Barred from attending the Beijing funeral of former top Communist Party official Bao Tong, Chinese pro-democracy activists and dissidents took to the internet to mourn his death, and some were able to send floral wreaths to Tuesday’s ceremony, according to their Twitter posts.

Around 100 people, including Bao's closest relatives, attended the funeral at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, according to a tweet from Chinese journalist Ye Bing.

A former senior Chinese government official who was jailed for opposing the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, Bao remained a sharp critic of the Communist Party during decades in jail or house arrest. He was the former aide to premier Zhao Ziyang, who was ousted after being seen as too sympathetic to the students leading the Tiananmen Square protests. Bao died in Beijing on Nov. 9, just four days after his 90th birthday.

Anyone barred from the funeral was also kept from signing their names on any wreaths, independent political journalist Gao Yu, who was herself banned from attending, said via her Twitter account.

"We've all been marked as 'absolutely no way' [meaning that] we can't bid farewell to Elder Bao on his last journey, nor place our elegiac couplets in the Babaoshan meeting hall," Gao wrote.

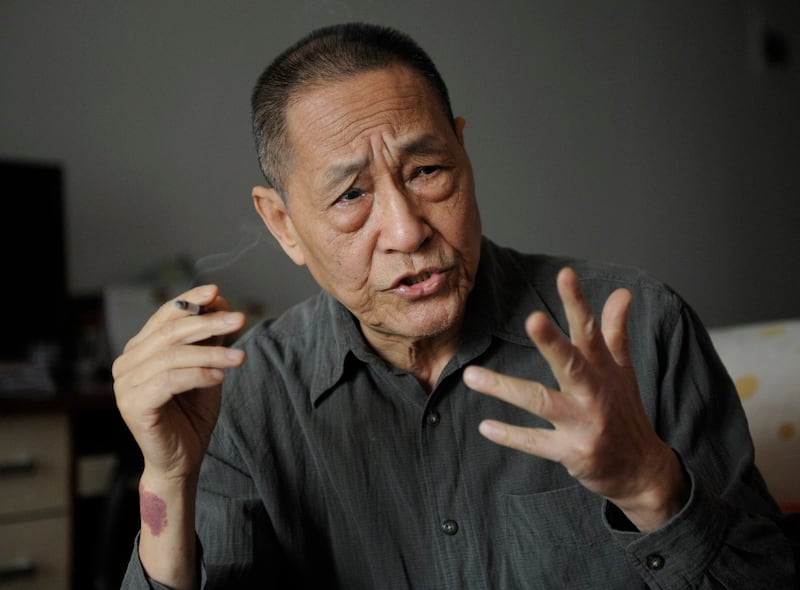

She posted a short video of photos and video footage of Bao, including where he is shown smoking and talking with people about why people stand up for their rights.

"What does it mean to stand up for your rights? It means to stand up for your right to live a normal life," he says in the clip. "When your right to live normally is violated, you must stand up for your rights."

Gao declined to comment when contacted by RFA, but said her tweets on the topic could be quoted instead of an interview, suggesting she had been warned off talking to the media about the funeral by the authorities.

‘Grief as high as the sky’

From overseas, friends and former colleagues paid tribute to Bao, who later served a seven-year jail term for "revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandizing" in the wake of Zhao's fall from power.

Stanford University researcher Wu Guoguang, a former colleague of Bao's in the 1980s, posted a lengthy tribute to Bao on his Twitter account on Tuesday.

"My grief is as high as the sky, and as wide as the ocean," Wu wrote. "My heart is broken and my soul is in mourning."

A number of the floral tributes to Bao came from the sons and daughters of former high-ranking Communist Party officials, including one from Wang Yannan, Zhao’s daughter.

Hu Dehua, son of late ousted party leader Hu Yaobang and Li Nanying, daughter of former secretary to Mao Zedong Li Rui were also named on wreaths left in the meeting hall, Ye tweeted.

Several other wreaths and elegiac couplets were only signed with surnames, while others carried only signatures like "Ms A," or "Mr A."

A person familiar with the etiquette around the funerals of former Communist Party officials said all messages and couplets attached to funeral wreaths would have been subjected to a strict vetting process, while the flowers themselves had to be ordered directly from the Babaoshan management office.

Rights lawyer Shang Baojun told RFA he had also been barred from attending Bao's funeral, while writer Ma Bo tweeted that three police officers had visited his home on Tuesday morning to prevent his family from going.

Fellow rights attorneys Pu Zhiqiang and Mo Shaoping were also prevented from attending, Pu said via his Twitter account.

Class of 1989

The funeral took place in the Plum Hall that is also available to the general public, rather than in halls reserved for state leaders or VIPs, Gao said, adding that it was the only public hall in operation at the time of the ceremony.

"Was this preferential treatment, or fear?" Gao tweeted, adding that she had sent a wreath along with a friend, as did overseas activists Zhou Fengsuo and Wang Dan, former leaders of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

Zhou's couplet read: "Mr. Bao Tong will go on forever, the ideal of democratic reforms will never die, and the condemnation of the June 4, 1989, massacre will never end."

"We of the class of 1989 want to express our gratitude to him loud and clear at this time," he told RFA. "I very much wanted to be able to voice this in Beijing, even though the number of people who would read it was very limited."

Bao’s name rarely appears in the official record, although he has a loyal following of former officials seeking to rehabilitate him as a figurehead of the reform era that began in 1979.

A keen political essayist, Bao was a long-term contributor of political commentaries to RFA Mandarin, wielding acerbic political commentary and gentle humor by turns, as well as providing contemporary accounts of key moments in the history of modern China.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.