Bao Tong, former top Communist Party aide to late ousted Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang, died in Beijing on Wednesday at the age of 90.

"Obituary notice for my late father Bao Tong, who passed away peacefully at 7.08 a.m. on Nov. 9, 2022, at 90 years of age," Bao's son Bao Pu said via his Twitter account.

"He is survived by a son, Bao Pu, and a daughter, Bao Jian," the tweet said.

Bao died just four days after his 90th birthday, according to Bao Pu, a Hong Kong-based independent publisher.

Bao Jian tweeted that her father had said on his birthday: "Humans live such minuscule histories on this earth. It doesn't matter whether I made 90 or not. What matters is today, and the future that everyone is striving for. You must do whatever you can. Do it today, and do it well."

Bao Tong did not appear in public for the funeral of his wife, Jiang Zongcao, who died of cancer on Aug. 21 at the age of 90. He was believed to already be in a Beijing hospital by that time.

At the time of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, Bao Tong served as director of the Office of Political Reform of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

A key ally of premier Zhao Ziyang, he later served a seven-year jail term for "revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandizing" in the wake of Zhao's fall from power.

Zhao was removed from office after then supreme leader Deng Xiaoping decided his approach to the student-led protests on Tiananmen Square in the spring and early summer of 1989 was too conciliatory.

According to an account of Zhao's fall penned by Bao as part of a commentary on the published diary of former premier Li Peng, Deng initially appeared to endorse Zhao's idea of a consultative approach to the students' demands, then excluded him and Bao Tong from a series of discussions that would eventually result in a hardline editorial appearing in the People's Daily on April 26, an irrevocable step towards the violent suppression that was to follow.

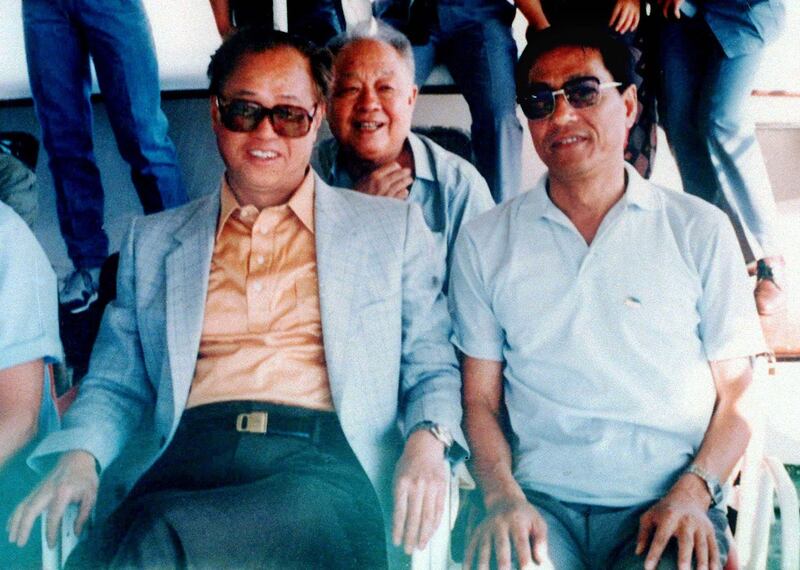

The shift to a hardline approach to the Tiananmen protests, which cast them as "counterrevolutionary turmoil," took place while Zhao was on an official visit to North Korea, and eventually resulted in the killing of an unknown number of unarmed civilians by the People's Liberation Army wielding machine guns and tanks on the night of June 3, 1989 and in the days that followed.

After his removal from office, Zhao spent the rest of his life under house arrest at his Beijing home, dying in early 2005 with his legacy largely erased from official history.

But Bao Tong remained a trenchant critic of the Chinese Communist Party, despite spending much of his later years under house arrest or close surveillance at his home in Beijing.

He was a prolific, long-time contributor of commentary on a wide range of Chinese and international issues for Radio Free Asia’s Mandarin service, although his output tapered off with declining eyesight and health in recent years.

In a further commentary on Li Peng's diary, Bao tied the events that led to Zhao’s and his downfall 33 years earlier to the current situation in China under President Xi Jinping.

"The massacre helped to found the current 'core' system, in which everyone is expected to be of one mind, in the world's most populous country," wrote Bao Tong.

“The massacre paved the way for countless layers of party control, from national government to the urban police, or chengguan, and the auxiliary police, to ordinary people and dissidents governed as ‘special households,’" and for the mantra ‘Follow the party and prosper: oppose it and die’ to be encoded into the minds of all Chinese citizens, he added.

Born in Haining in the eastern province of Zhejiang, under the Kuomintang-ruled Republic of China founded by Sun Yat-sen in 1911, Bao Tong grew up in Shanghai, and once wrote that he joined the Communist Party during his youth because he believed late communist leader Mao Zedong's "lie" that the party would implement a government based on Lincoln's "for the people, by the people and of the people" principles, known as the Three Principles of the People in Chinese.

He later rose to become a member of the 13th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and political secretary to Zhao Ziyang, with responsibility for attending top-level meetings and drafting documents relating to their decisions.

Bao Tong was arrested in Beijing on May 28, 1989, then expelled from the party and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.

Former Tiananmen activist Wang Juntao praised Bao's commitment to the pursuit of freedom and democracy throughout his life, and his trenchant analysis of Communist Party rule.

"Mr. Bao has left us at the darkest moment in China's history," Wang told RFA. "As someone who fought for the Communist Party in the first half of his life, before being persecuted by them in the second half of his life, he grew old in the hope that China would see freedom and democracy one day."

"He saw all of the party's problems, but also once held a kind of hope that it could solve its own problems," he said. "In the end, he was himself once more the target of its persecution."

Former Beijing News founding editor Cheng Yizhong said he could remember watching Zhao Ziyang speaking to students on Tiananmen Square while he was a university student in the southern province of Guangdong in 1989, and feeling inspired by what he was saying, a rare reaction from those hearing Chinese leaders' speeches.

"Bao Tong was one of the main architects of Zhao Ziyang's political thought," Cheng told RFA. "He had a massive impact on Zhao Ziyang and even on the wave of liberal thinking among Chinese intellectuals during the 1980s."

"He was one of only two true rebels in the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party, which was laudable," he said of Zhao, naming the second as party co-founder Chen Duxiu.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie and Paul Eckert.