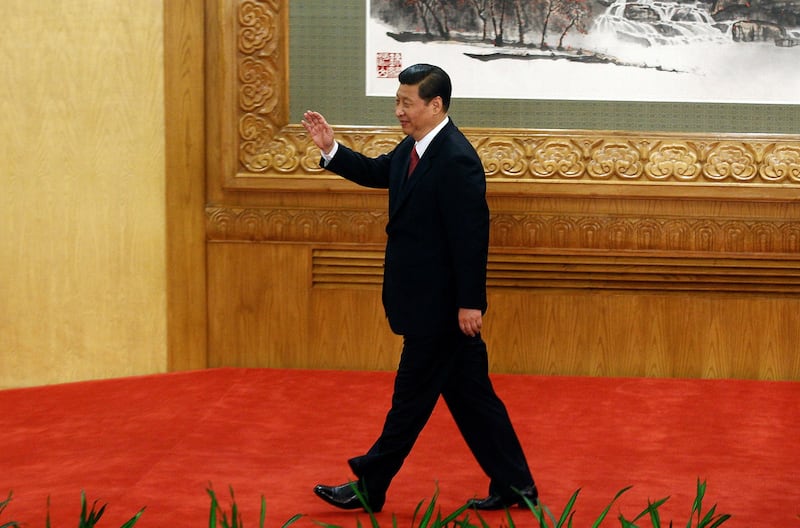

The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which convenes in Beijing on Oct. 16, is expected to grant an unprecedented third five-year term to Xi Jinping, the CCP general secretary and state president. In the run up to the congress, RFA Cantonese and Mandarin examined the 69-year-old Xi's decade at the helm of the world's most populous nation in a series of reports on Hong Kong, foreign policy, Chinese intellectuals, civil society and rural poverty.

Ten years after ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Xi Jinping came to power, China's once-nascent civil society appears to have died in infancy, activists and rights lawyers told RFA, as Xi gears up to seek a third, possibly indefinite, term in office at the forthcoming party congress.

China was described back in 2008, after the Sichuan earthquake, as being "on the threshold" of having a functioning civil society.

Fast forward a decade, and a research paper penned by civil society researchers at Peking University describing the development of civil society as one of China's greatest achievements, looks like a moldering historical document from a bygone era.

Human rights attorney Wang Quanzhang said the Xi administration has largely nipped that development in the bud, because civil society is seen by the authorities as a thorn in their side.

Wang said the government has gotten it wrong, because civil society groups ease social tensions and offer aid where the government doesn't, contributing to social stability.

"If civil society cannot develop, then the rest of society will be less and less balanced, giving rise to continual and extreme cases of social conflict," said Wang, who was released in 2020 after a four-and-a-half year jail term for subversion in connection with the public interest cases he was involved in.

"Chinese people have been oppressed by various organizations for a long time, throughout their history, without any independent civil entities to support them," he said. "The stress on the individual can be enormous."

China started the 21st century on a note of hope, with the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games and its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) already in the bag, and appearing to presage an era of unprecedented liberalism.

But rapid economic development began to expose growing social inequality, and its attendant social problems.

Pressed to shut down

A number of non-government groups took advantage of what was once a relaxed regulatory environment to offer assistance and services to people in need, among them a group called the Beijing Transition Research Institute, or Chuanzhixing, which said it was "committed to investigating issues and phenomena related to freedom and justice in the process of social transformation."

Group founder Guo Yushan once helped rights lawyer Chen Guangcheng with his daring escape from house arrest at his home in the eastern province of Shandong, enabling him to take refuge in the U.S. Embassy in Beijing.

Guo also helped the families of children sickened during the melamine-tainted infant formula scandal of 2008, and grew into one of the better-known rights groups.

U.S.-based activist Yang Zili, who used to work for Chuanzhixing, dates the beginning of the end for the group when Xi Jinping came to power at the 18th party congress in 2012.

"Civil society was suppressed very soon after Xi Jinping came to power," Yang told RFA. "It started with a growing number of restrictions on the organization's activities, before it was banned outright."

"We used to hold a weekly lecture, and it started when the authorities wouldn't let us have a politically sensitive guest speaker who was going to talk on a politically sensitive topic," he said.

"They eventually interfered to the extent that they wouldn't let us hold [the lectures] at all," Yang said.

The Beijing municipal government banned Chuanzhixing outright in July 2013, saying it had failed to register with the authorities in the correct category.

Other civil society groups were soon to meet the same fate.

The Liren Rural Library grassroots educational project, which built libraries in rural schools, health rights advocacy group the Beijing Yirenping Center, and the Unirule Institute of Economics all gradually disappeared from view.

"Organizations like Liren and Chuanzhixing, where I worked, have all been wiped out now," rights activist Chen Kun told RFA.

"Their employees have either gone abroad, been imprisoned, or have no way to speak out on these matters any more," he said.

Harsh environment

Josef Benedict, a researcher at the Asia-Pacific Department of the Global Civil Society Engagement Coalition (CIVICUS), an international non-profit organization headquartered in South Africa, said China is now one of the world's most closed societies.

Activists have to work in extremely harsh environments, with the recent crackdown meaning that NGOs have basically lost any autonomy, and with most of the better-known groups shut down by the government, Benedict said in comments emailed to RFA.

Elizabeth Plantan, an assistant professor of political science at Stetson University who studies Chinese civil society, said the government appears to be encouraging environmental groups, however.

Activists and NGOs working on environmental issues locally, regionally and nationally are still able to operate relatively freely, especially in the area of environmental public interest litigation, Plantan told RFA.

Groups promoting government transparency around pollution data and that cooperate with state actors via official think-tanks are also tolerated, she said.

But she said that Chinese leaders' antipathy toward civil society is well-documented, and unlikely to wane.

Civil society is clearly listed as one of the "seven taboos" in the CCP's Document No. 9, a leaked secret policy document from 2013 that also bans public discussion of judicial independence, universal values, press freedom, citizens' rights, the historical mistakes of the CCP and the country's financial and political elite.

Maya Wang, senior China researcher at the New York-based group Human Rights Watch (HRW), said the banning of civil society groups has weakened social cohesion rather than threatening it.

"Currently, Chinese society can be said to be atomized, which means that under a totalitarian regime, people are isolated and can only rely on their families for any kind of assistance," Wang told RFA.

"It is difficult for people to connect with each other or to do anything together," she said.

Changed forever

Wang Quanzhang, who was one of dozens of prominent rights lawyers detained, imprisoned or otherwise targeted during a nationwide operation targeting the profession in 2015, said that crackdown had changed the situation of rights attorneys forever.

While they had been targeted in the past, the authorities began pursuing them at a far greater rate during the second five years of Xi Jinping's tenure at the helm of party and state.

In the 18 years from 1998 to 2015, 29 Chinese lawyers were stripped of their right to practice for representing human rights cases.

Between 2016 and 2021, that number had risen to 42.

"The July 2015 arrests were yet another small peak in the authorities' crackdown on citizens' rights protection and human rights lawyers," Wang told RFA.

"Since then, the activities of civil society groups like human rights law firms have been further restricted and compressed," he said.

Rights lawyer Wang Yu told a recent online conference organized by U.S.-based groups that her license to practice was revoked in 2020, and that she has so far had little success in offering legal assistance to clients without it.

Wang was suddenly rendered incommunicado in 2021, after being named by the U.S. State Department as an International Woman of Courage.

Sources told RFA at the time that the authorities had prevented her from attending the online award ceremony and from speaking to the media.

Guangzhou-based rights lawyer Sui Muqing, who was also targeted in the 2015 crackdown, said his license was revoked in 2018.

"I think the environment for civil society has obviously gotten very bad," Sui told RFA. "It's not just human rights lawyers and activists."

"Intellectuals and people inside the system [of government] are affected by the chilling effect, too," he said.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.