China has announced the baseline that defines its territory in the northern part of the Gulf of Tonkin that it shares with Vietnam.

In a statement published on the foreign ministry’s website early this month, the Chinese government released a set of seven base points that, when connected, would form a new baseline for Beijing’s claims of sovereignty in the Gulf of Tonkin, known in China as Beibu Gulf.

This baseline did not exist before and it is unclear why China decided to announce it now. On May 15, 1996, Beijing released 49 base points for the entire China's coast from Hainan to Qingdao but not the northern Gulf of Tonkin.

“Some of the base points are too far from the coast and the baseline appears seriously incompliant with the U.N. law of the sea,” said Song Phan, a Vietnamese maritime analyst.

“Vietnam and China already signed an agreement on the demarcation of the Gulf of Tonkin in 2000 with a clear demarcation line, so the new baseline is not expected to hurt Vietnam’s economic interests very much as long as Beijing does not ask to re-negotiate,” he said, “But it would bring complications to other maritime activities in the area.”

Another maritime expert, Carl Thayer, emeritus professor at the Australian Defence Force Academy, said the straight baseline “appears excessive.”

“It would result in a bigger overlap of China’s exclusive economic zone with the agreed median line and joint fishing areas [between Vietnam and China] in the Gulf of Tonkin,” Thayer said.

What is a baseline?

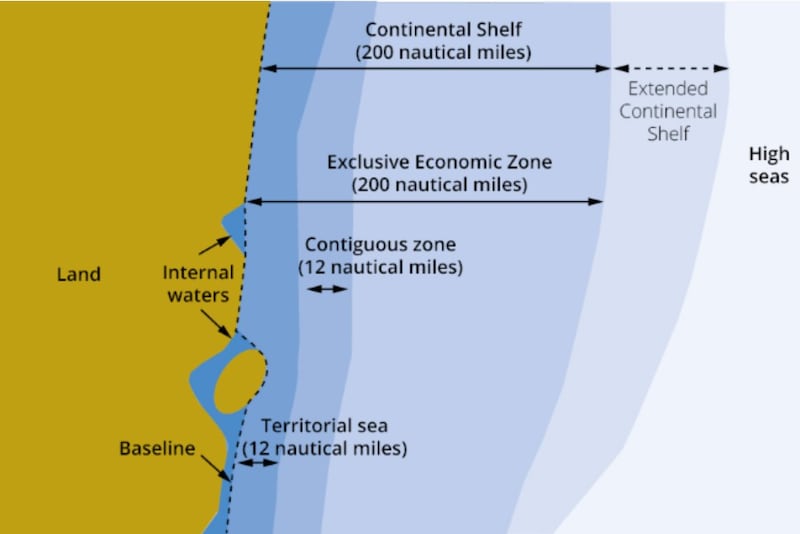

A baseline under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the line that runs along the coast of a country, from which the extent of the territorial sea and other maritime zones is measured. Different maritime zones give a coastal state different jurisdictional rights, and the closer the zone to the baseline the bigger its associated jurisdiction rights.

Landward inside the baseline are internal waters where states have the same sovereign jurisdiction as they do over their land territory. No foreign vessels or aircraft are allowed to make so-called innocent passage through a country’s internal waters.

The territorial sea, measured 12 nautical miles from the baseline, is where the coastal state has sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction not only to the sea, but also to the seabed and subsoil, as well as vertically to the airspace. Foreign aircraft cannot fly through the airspace above the coastal state’s territorial sea without permission.

Some countries, such as China, Taiwan and Vietnam, also require permission or notification before a foreign warship can sail through their territorial seas. Beijing has repeatedly protested against U.S. warships’ sailing in waters near the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos, which Washington insists is conducted in accordance with international law.

“The new baseline would affect freedom of navigation activities, scientific research, cables or pipelines laying and island reclamation works,” said Song Phan.

“More importantly, the expansive internal waters mean there will be no access for any other country to a large area,” he added.

Hanoi has not reacted to the Chinese government’s announcement.

“To my mind the new line looks incompatible with the wording of UNCLOS,” said Bill Hayton, Associate Fellow at Chatham House think tank in London.

“However, since the median line with Vietnam is already defined, I don’t think it will have a major impact,” Hayton said.

“Hanoi could object and take China to a tribunal but I don’t think it would gain anything,” he added.

In 2016, a landmark arbitral tribunal brought by the Philippines ruled against all China’s claims in the South China Sea but Beijing has rejected the verdict, calling it “illegal, null and void.”

Edited by Elaine Chan and Mike Firn.