Chinese state media and netizens have piled onto social media in recent days to sing the praises of a homegrown web drama about a jade teapot that escapes from the British Museum and tries to get home to China.

The three-part drama, "Escape from the British Museum," shows the green-clad "teapot" personified as a young woman accost a Chinese man in the street, asking for help.

"I've been wandering around out here for ages, cousin," she tells him. "I'm lost, and can't find my way home."

The nationalistic drama has proved a hit with the online army of nationalist " little pinks," and was released around the same time as a Global Times editorial calling for the return of Chinese artifacts from the scandal-hit British Museum, which fired a staff member last month after some of its collection was found for sale on eBay.

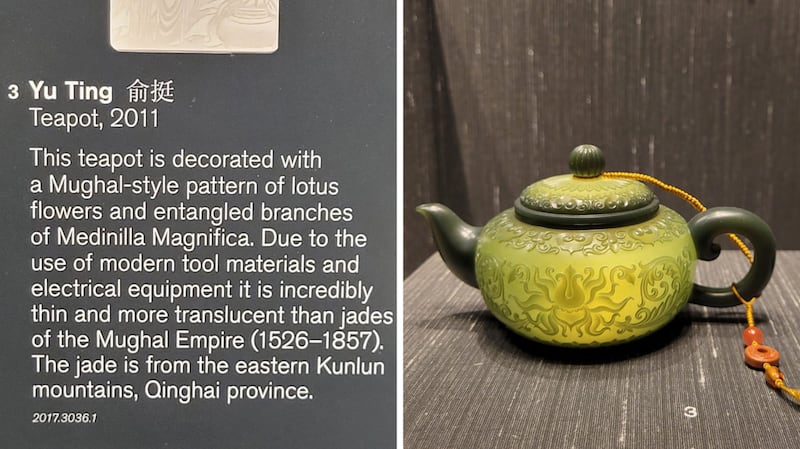

Never mind that the explanatory text about the teapot referenced in the film states it was actually made in 2011 by Suzhou master jade carver Yu Ting, who sent it to be displayed in the museum.

"While the British Museum proudly displays over 23,000 Chinese artifacts, most of which were obtained through improper channels, even dirty and sinful means, questions loom over their acquisition history and the larger issue of repatriation," Global Times said in an infographic on Sept. 4.

‘Bloody, ugly and shameful’

Earlier, the paper published an editorial calling the museum "the world's largest receiver of stolen goods."

"The UK, which has a bloody, ugly, and shameful colonial history, has always had a strong sense of moral superiority over others," it said. "We really do not know where their sense of moral superiority comes from."

In the web drama, the young man takes the eccentric teapot woman home to his elegant apartment, sleeping on the sofa and taking her on a whistle-stop tour of U.K. tourist spots including the white cliffs of Dover, before eventually telling her "Come on, we're going back to China."

The couple then take in a military parade complete with goose-stepping soldiers on Beijing's Tiananmen Square.

"Thank you, Yong An," she tells the young man, whose character takes his name from a ceramic pillow emblazoned with the words "eternal peace for family and country" on display in the British Museum. "This has been the happiest and brightest time in my tiny world."

‘No. 1 robber’

The young producers, who also act in the film, told ruling Chinese Communist Party newspaper, The People's Daily, in an audio interview posted to Weibo on Sept. 8 that they decided to release the show early after seeing the news last month that the British Museum had sacked a member of staff and reported around 2,000 cultural relics missing to Scotland Yard.

“This is about the emotions we felt after a visit to the British Museum," one co-actor and producer who gave only the pseudonym Xiatian Meimei told the paper.

"While we were filming at the British Museum, we ran into a lot of foreigners [sic] who didn't understand much about our cultural artifacts," director Zhang Jiajun, a Douyin blogger and film school graduate said. "They are Chinese treasures that carry a lot of Chinese culture."

"When they are overseas, people don't really understand them, because they lack the cultural genes to do so," he said, using a buzzword that has become popular under Chinese leader Xi Jinping. "We hope people will pay more attention to the issue of cultural artifacts overseas."

The drama drew a large number of nationalistic comments, with one comment saying "I'm going to cry myself to death," and another saying: "We must take back what belongs to China."

"The British Museum is the world's No. 1 robber," said another.

Returning relics?

Another article in the Global Times called on Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Secretary James Cleverly, who was visiting China at the time, to change the law preventing the return of artifacts in the museum.

The British Museum was established by an Act of Parliament in 1753 and is currently governed by the British Museum Act 1963.

It has so far refused to return the Elgin Marbles from the temple of Athena to Greece, ceremonial items and other artifacts taken during 19th century military action to Ethiopia, the 900 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria or gold items belonging to the Asante people of Ghana, according to the BBC.

U.K.-based commentator Chen Liangshi said much of the anger over Chinese artifacts ignores the mass destruction of cultural items during the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, and that many of the items now in overseas museums could have been destroyed if they had stayed in China.

He added that many of the artifacts in the British museum were bought rather than looted, or donated by collectors after changing hands several times.

U.K.-based Hong Kong historian Hans Yeung agreed, also citing the widespread destruction of the Cultural Revolution and the whipping up of nationalistic sentiment online.

"They went after the United States, then they went after Japan," he said. "Now they're done with Japan, they're going after the U.K."

U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has accused China of meddling in Britain's democracy as he faces a government split at home over whether to formally designate China a threat to national security.

Meanwhile, a brief survey of publicly available information by Radio Free Asia found that more than 100 Chinese cultural artifacts came from the donated collection of Irish physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloan, while thousands more were donated from the collection of antiquarian Sir Augustus W. Franks.

Many more were sold by Chinese aristocrats, officials and scholars for cash around the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911.

Against the flow

Not all Chinese media played along with the nationalistic angle.

The Guangzhou-based newspaper Southern Weekend published an article titled: "Is it really a good idea to mix up cultural relics with handicrafts to generate patriotic traffic?"

However, links to the article resulted in a 404 error message on Monday, and the article was criticized by at least two nationalistic commentators on social media.

British Chinese author Ma Jian said there are also question marks around the ownership of cultural artifacts from imperial China.

"The government may think it's all great fun when internet influencers stir up trouble like this, but Chinese officials won't really do anything, because it's not in their interest," Ma said.

"Returning items calls for expertise, and you have to ask them to specify which item they want ... then trace the provenance, and find out who the original seller was, and then decide who the item should be returned to," he said.

"This is a huge job, one that will take 10, 20 or hundreds of years, not just something that can happen because some online influencers casually call for it."

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.