[ Read RFA’s coverage of this in Chinese.Opens in new window ]

In 2013, former politics lecturer Chan Kin-man, law professor Benny Tai and Rev. Chu Yiu-ming called a news conference to urge people to occupy Hong Kong's Central business district in a peaceful civil disobedience campaign for fully democratic elections.

Many feared Beijing would not allow it despite promises made during the negotiations for the 1997 handover from Britain.

The following year, the ruling Chinese Communist Party issued a plan on Aug. 31 setting out Beijing's plan for reforms of the electoral system that would give everyone a vote – but would also ensure that only candidates approved by the government would be allowed to run in elections.

The public backlash amid growing calls for genuine democratic reform took the form of a student strike, camps on major roads, sit-ins, mass rallies of hundreds of thousands of people and an unofficial referendum that came out overwhelmingly in favor of open nominations for electoral candidates.

While the authorities refused to back down, saying there was ' no room' for discussion on the electoral rules, police fired tear gas and beat protesters in clashes that began this week 10 years ago.

To protect themselves, demonstrators used umbrellas, and the “Umbrella Movement” was born.

‘Watershed’ moment

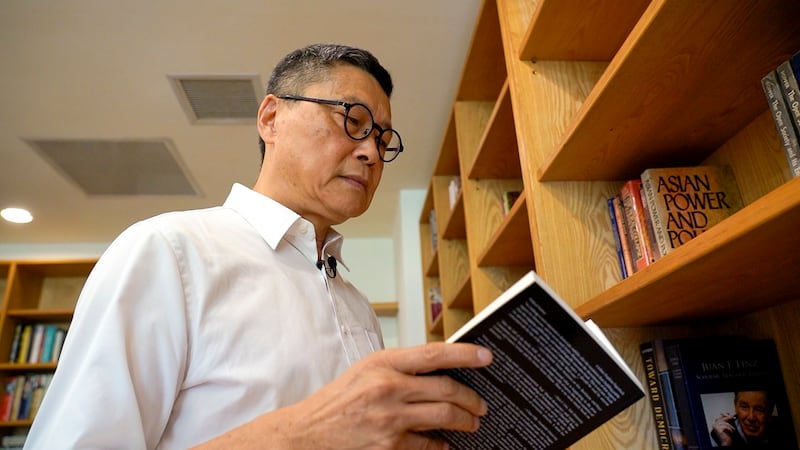

Ten years on, Chan, now 65 and living in Taiwan, told RFA Mandarin that the movement -- and the authorities' response -- served as a wake-up call to many in Hong Kong who may not previously have considered themselves political at all.

Describing the 2014 movement as a "watershed" for Hong Kong, Chan said it turned his home city from a money-oriented former colony to a society that was willing to take radical action to protect its promised rights and freedoms.

"The Umbrella Movement of 2014 was a watershed," he said. "It was the first time we had used a so-called illegal method -- that of occupation.”

“It was a citizens’ resistance movement, fighting for democracy on a huge scale,” Chan said, adding that an estimated 1.2 million people were involved at some point during the movement.

“People who took part were willing to pay the price of legal action,” he told Radio Free Asia.

“The biggest impact of the pro-democracy movement was on people’s political awakening – people who hadn’t paid much attention to the issue in the past ended up joining in and caring what was happening,” he said.

“The fact that many more people just watched from the sidelines doesn’t mean it didn’t have an impact on them.”

Deeply etched memories

Ten years on, the scenes he witnessed on Hong Kong's streets remained deeply etched into Chan's memory.

"I remember seeing one lady at the Occupy site who was very conventionally dressed,” he said. “She didn’t look at all like the protesters.”

“She ran a business near Admiralty, and I started to apologize to her, saying our occupation was likely affecting her business, but she told me never to apologize, and that she wanted to thank me,” Chan recalled.

The woman told Chan that she hadn’t been remotely interested in politics before this happened, but since then she’d started reading more news reports, and she had come to understand why the occupation was happening.

"She started to feel that she had been in the wrong all these years, for not paying much attention to Hong Kong's political development, and just being focused on making money,” he said. “She felt she was letting the next generation down.”

While the Umbrella Movement did have its critics among those who blamed it for accelerating China's meddling in the city's political affairs, Chan said Beijing had left young Hong Kongers with little option but to take to the streets.

“It’s simplistic to look at whether the movement succeeded in changing the system overnight – it managed to mobilize 1.2 million people and continue an occupation for 79 days,” Chan said.

“Not many movements in the history of the world have managed that.”

More militant

And when the movement failed to pressure the authorities into allowing properly democratic elections, it was inevitable that the next round of protests in 2019 would become much more militant, he said.

"When even civil disobedience fails, and there is no way to fight for democracy [under Chinese rule] using peaceful means, there is going to be a move towards localism and militancy," Chan said. "We warned people about this at the time."

"Young people were very dissatisfied and impatient, and they were already starting to agitate [for a more radical approach]," he said. "This was a critical movement, but the root cause of it all was the authoritarian approach of the Chinese Communist Party."

"It was they who forced the people of Hong Kong, bit by bit, down the road to civil disobedience," Chan said. "The whole thing stems from the fact that the Chinese Communist Party rejects and resists democracy at every turn."

When protests against plans to allow extradition to mainland China erupted in 2019, Chan was still in prison. By the time he got out in 2020, the National Security Law had already been imposed on the city, ushering in a crackdown on public dissent and peaceful political opposition.

Fleeing to Taiwan

When Benny Tai was arrested alongside dozens of former pro-democracy lawmakers in 2021, Chan fled the city for Taiwan.

He still keeps a close eye on developments there, but is unclear whether resistance of the kind he proposed in 2013 is even an option these days, now that the authorities have two national security laws to use against dissenting voices.

"Overt resistance hasn't been possible since the National Security Law came out [in 2020], but it's too early to say whether Hong Kong is dead or not," he said, citing plummeting turnout figures in recent elections under Beijing's new, highly restrictive rules.

"A lot of people may still be holding onto their beliefs -- the authorities say that this is a form of soft confrontation," he said of the recent lack of interest in voting.

"But that would mean people haven't died inside,” Chan said. “And that means there's still hope.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.