[ Read RFA’s coverage of this in Chinese.Opens in new window ]

Seventy-five years after Mao Zedong founded the People's Republic of China, his legacy is still being felt in the form of mass political campaigns and witch-hunts that keep the people divided while shoring up Communist Party rule, analysts and scholars said.

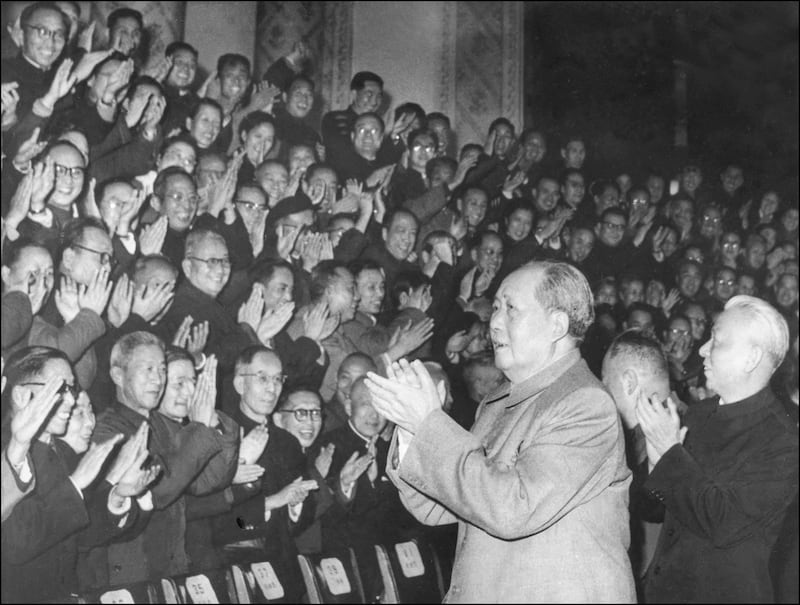

While Mao's announcement from the rostrum of Tiananmen Gate was intended to deliver the message that China was under new management following decades of colonial humiliation and war, it actually ushered in further political and social turmoil and set a pattern that is being repeated under party leader Xi Jinping today, experts told RFA Mandarin.

The evaluation of China's recent past isn't just about history, they said. It is closely bound up with the current political line in Beijing -- to criticize Mao, albeit slightly, is to indicate a move away from his policies, while to echo him, as current leader Xi Jinping has done repeatedly in recent years, indicates a more left-leaning direction.

Zhou Xiaozheng, a 78-year-old former professor at Beijing's Renmin University of China, remembers no less than 56 political campaigns while he was in high school, sparked by a June 1, 1966, editorial in the People's Daily calling on people to "sweep away all cow demons and snake spirits," a reference vague enough to encompass all manner of political "enemies."

"Mao Zedong's biggest harm lay in his criticisms of Chinese culture," Zhou told RFA Mandarin. "And culture begins with education."

"He sent 20 million school-age youngsters to the countryside, and I was in the first batch -- I went to Heilongjiang in 1968, where I was a farmer for 10 years," he said.

Tools to keep power

But the upheavals didn't end with the death of Mao in 1976, where many historians typically place the end of the Cultural Revolution, Zhou said, adding that the party is still living out the Great Helmsman's legacy by using his political campaigns as a tool to remain in power.

"The fact that Mao's portrait still hangs in Tiananmen Square today proves that the Cultural Revolution isn't over yet," he said.

In fact, the campaigns were already coming thick and fast from the start of the "New China," with the land reforms of 1949 targeting landlords and rich farmers, often by lynch mob.

They were followed in short order by the movement to suppress "counterrevolutionaries," the “Three Antis” and “Five Antis” movements targeting wealthy urban capitalists and former members of the defeated Kuomintang, which by then had fled to Taiwan.

By the late 1950s, Mao was targeting political opponents within party ranks who weren't traditional "enemies of the people," launching the Anti-Rightist Campaign that mopped up anyone to the right of Mao, including intellectuals who still held out for a better form of representative democracy, or just people he viewed as a political threat.

By the Great Famine of 1959-1961, during which a former aide to future ousted premier Zhao Ziyang estimated the number of deaths at 43-46 million, political upheaval and social unrest was becoming a way of life.

Struggle sessions

It seemed that the turmoil played into Mao's hands because he kept instigating more internecine "struggles" in the guise of the Cultural Revolution, right up until his death.

"I started primary school during the early days of the Cultural Revolution, at the age of 6," poet He Sanpo told Radio Free Asia.

"The first page of our Chinese class textbook had the phrase 'Long Live Chairman Mao!' printed on it, while the second was 'Long live the Chinese Communist Party!' and the third had 'Long Live the People's Republic of China!'"

"There was a huge portrait of Mao Zedong hung high on the walls of the school, in the commune and in every household, looking down on us all of the time," he said.

There wasn't much formal teaching, as children were marched off to the town square to take part in "struggle sessions,” where police, soldiers and commune leaders would sit with stern expressions, announcing the list of "crimes" committed by those being targeted as "landlords," "rich peasants," "counterrevolutionaries," "bad elements" and "rightists," He recalled.

"The sound of the loudspeakers vibrated through the ground, and the people being struggled against were tied up and stood looking dejected in the scorching sun, sweating profusely," he said. "Next to these members of the 'five black categories' stood militiamen with rifles, poised to leap in and punch and kick them at any time."

He said such scenes likely impacted an entire generation of kids, who were also roped into revolutionary theater and propaganda shows that toured local towns and villages, praising Mao, the party and socialism.

"I believe that the generation that went through the Cultural Revolution was left with deep-rooted psychological trauma," he said. "The whole country was a madhouse -- all of the adults were out of their minds, and all manner of absurd dramas were repeated, day in, day out."

Destroyer

Du Wen, a former executive director of the Legal Advisory Office of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region government, who now lives overseas, said many adults were destroyed by the turmoil too.

"Mao destroyed China's intellectual elite and the foundations of the Chinese economy," Du said. "The political campaigns were endless, and countless innocent people suffered."

"Anyone who still had illusions about the Chinese Communist Party lost them," he said.

While estimates from overseas historians are more conservative, revolutionary leader Ye Jianying once estimated that around 100 million people were persecuted, 20 million died and 800 billion yuan was wasted during the Cultural Revolution alone.

Yet Mao's successor, the former persecuted "rightist" and economic reformer Deng Xiaoping, couldn't put an end to Mao's political legacy entirely.

While Deng appeared to take China further to the right, he never fully relinquished the party's control over society as became painfully clear when he ordered the Tiananmen massacre in 1989, Du said.

"My teacher once said that with Deng Xiaoping, the abused became the perpetrator," he said. "Now it's happening again with Xi Jinping."

Hong Kong-based journalist Ching Cheong thinks Xi has continued Mao's legacy largely through an ongoing process of "brainwashing" throughout a child's education, raising the next generation to think like patriots and nationalists, bullying others into accepting their point of view, rather than engaging in informed debate.

"For the past 75 years since seizing power, the Chinese Communist Party has deployed large-scale, continuous, comprehensive, coercive, and high-pressure brainwashing operations on its people," Ching wrote in a commentary for RFA Cantonese marking the 75th anniversary of the People's Republic of China. "The powerful people created by this process are decivilized."

Purging and indoctrination

Ching identified two stages of the brainwashing process: purging and indoctrination.

"What does it clear out and what does it instill? It removes the moral bottom line of human society, the ability of ordinary people to think for themselves, and their conscience," he wrote. "Then it instills the Communist Party’s philosophy of struggle, a narrow nationalism and distorts their view of who is a friend and who an enemy."

That process then makes people willing to accept the framing -- however nonsensical -- of the next political campaign, from the "rightists" of the 1950s to the "counterrevolutionaries" of the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement, to the "tigers and flies" of Xi Jinping's anti-corruption movement, Ching said.

Writer Tong Tianyao, whose grandparents lived through the Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution, grew up in the economic boom-years that followed Deng's ascendancy, part of a generation that avoided anything political like the plague.

This is no longer the case for Tong, however.

"This kind of avoidance doesn't work because true civilization is based on a widespread concern for the political life of the nation," she said. "Politics can protect people's interests from being eroded, but it can also quickly and totally destroy people's lives."

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.