The Chinese government is considering cutting red tape around marriage registrations in a bid to encourage more young people to tie the knot.

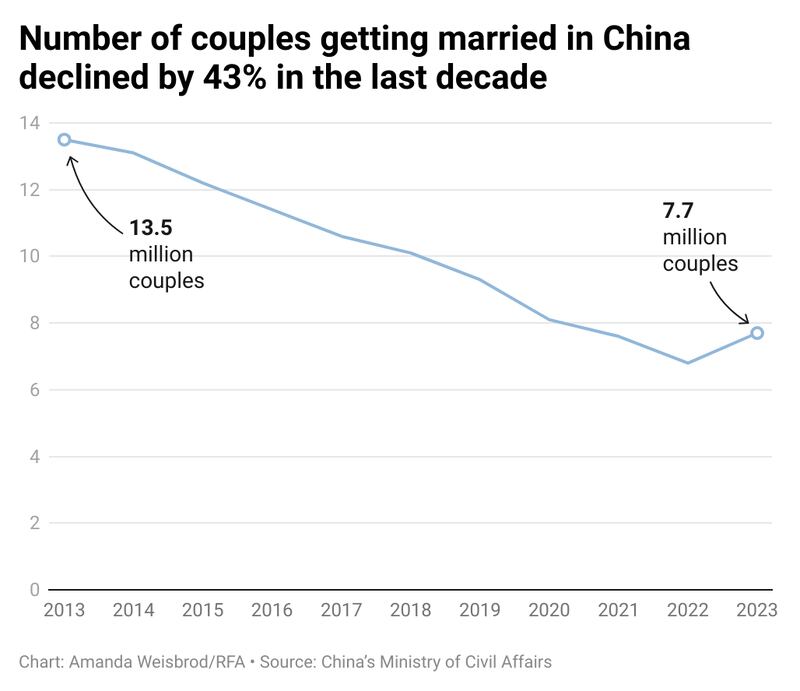

The number of Chinese couples getting married for the first time tumbled 8.3% in the first quarter, government figures show, resuming its slide over the past decade amid a tanking economy, rampant youth unemployment, growing awareness of gender equality and changing priorities.

Marriages rebounded 12% last year after the end of the COVID-19 restrictions, but the bounce was short-lived. Over the past nine years, first marriages have plummeted by nearly 56%, according to the 2023 China Statistical Yearbook.

That's contributing to a sharp decline in birthrates and a shrinking, aging population – a trend that the United Nations projects will lead China's population to contract from 1.4 billion to 800 million by 2100.

As more young people stay single, the Ministry of Civil Affairs published draft changes to marriage rules that would drop the requirement for couples to produce their household registration, or hukou, documents when getting hitched.

The new rules, proposed in an Aug. 12 consultation document on the ministry's website, would also bring in a new, compulsory 30-day delay to divorce applications, billed as a "cooling off" period.

One-child policy fallout

Three decades of the “one-child policy,” which ended in 2015, has also taken a toll: There are fewer young people – and an imbalance between men and women.

There are currently 17.52 million more men aged 20-40 than women, yet the proportion of single women has risen tenfold in the last decade, according to Yuan Xin, vice president of the China Population Association.

While some welcomed the new proposals because they cut out red tape, a 26-year-old woman who gave only the pseudonym Angela for fear of reprisals said they wouldn't make her more likely to want to marry.

"It makes sense to lose the requirement to produce your household registration document, because ... marriage and divorce are personal freedoms, and have nothing to do with where your household is registered," she said. "But making it easier to get married doesn't necessarily mean that more people will want to marry."

RELATED STORIES

[ China sees a sharp drop in marriagesOpens in new window ]

[ Faced with decline in marriages, Xi calls on women to build more familiesOpens in new window ]

[ For China’s ‘young refuseniks,’ finding love comes at too high a priceOpens in new window ]

"People who want to marry will do it regardless of how complicated it is, and those who don't will be unaffected," she said. "You can't change young people's decision about whether or not to marry just by changing a rule."

She said the plan had sparked an angry reaction on social media. "Young people online are 10 times angrier about it than I am," she said.

Financial and emotional factors

Overseas-based rights activist Xiang Li said the flagging economy, higher education levels among women and a sense of despair about China's future are all contributing to young people's reluctance to tie the knot, and sign themselves up for more financial responsibility than they already bear.

"At a time when the socioeconomic situation is so depressed, getting married will just make people more financially stretched, because they will have to buy somewhere to live," Xiang said. "Things won't improve unless the social and political situation changes."

Millennial Li Dong, who hails from the southwestern province of Yunnan, said she only knows three people who have married out of her class in high school, and many more have no plans to wed at all.

"What [those who have married] have in common is that they are working locally, and have fairly stable jobs," Li said. "Most [women in my class] have had boyfriends, there are many who don't plan to marry and who basically don't trust men."

"Very few of them will even think about marrying before the age of 30," she said.

Last week, a keyword search term about the rising proportion of unmarried women made the list of top searches on the social media platform Weibo.

One comment on the topic read: "It will continue to increase significantly every year in future too, never fear."

Another said: "This will become the norm," while another pointed out the apparent gender bias in the topic at hand: "We know that there are more men than women, but yet it's the single status of women that's being talked about," the user wrote.

COVID toll

According to Xiang Li, three years of grueling lockdowns, mass quarantine and compulsory testing during the pandemic that ended amid nationwide protests in 2022 have taken a huge emotional toll on young people.

"During the three years of zero-COVID, China turned into a huge prison, with even Shanghai turning into a concentration camp like Xinjiang," Xiang said. "The young people in the 'white paper' protest movement were shouting that they were the last generation, who didn't need to marry or have kids."

She summarized their message as "we are the last generation to be exploited by your authoritarian government.”

"There are also a lot of divorced people who have been hurt by marriage, and are very reluctant to marry again," Xiang said.

And while young men in rural areas may still wish to find a wife, they may not be able to afford it.

"There's a bachelor crisis, meaning that the bride price in rural areas is sky-high at the moment, and the cost of getting married is very high," Yi Fuxian, a senior researcher and demography expert at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told RFA Mandarin in a recent interview.

"The serious gender imbalance makes it hard and very costly for men to find wives," Yi said. "A lot of money is spent on marriage, which leads to a lot of debt in the wider family."

"The money goes on buying property and cars, and there are also loans to repay," he said, adding that many people now believe that the single life is more carefree.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.