The Hong Kong government has ordered the removal of a digital billboard installation containing the names of those who took part in the 2019 protest movement, while national security police have detained at least six former members of a now-disbanded pro-democracy labor union for questioning.

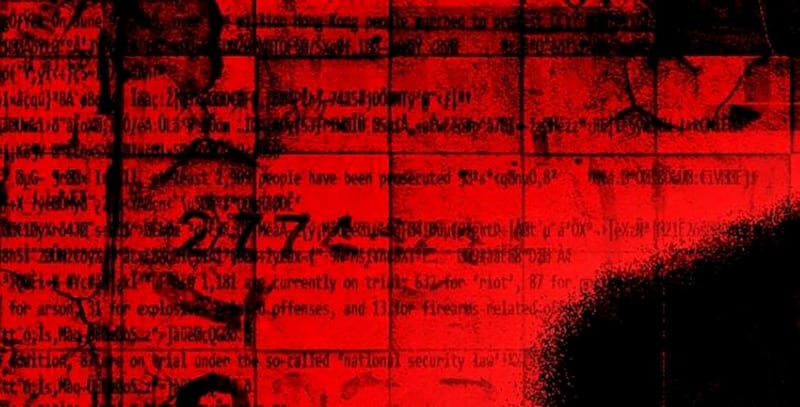

A piece by U.S. digital artist Patrick Amadon titled "No Rioters" was taken down from a digital display screen on the Sogo department store in Hong Kong's Causeway Bay shopping district, the artist said via his Twitter account.

"NO RIOTERS was taken down today at the request of the government," Amadon, whose work included the names of protesters from the 2019 democracy movement, tweeted with a fist emoji.

The takedown came after the work was criticized by the Communist Party-backed Ta Kung Wen Wei media group in Hong Kong, which accused it of "supporting the rioters" following a frame-by-frame examination of the work, in which segments of text flash up briefly against the background of a moving surveillance camera in black and red.

Public support for the 2019 movement, which began as mass protests against the erosion of Hong Kong's promised freedoms and broadened to include demands for fully democratic elections and great official accountability, has been outlawed under an ongoing crackdown on dissent in the city under a draconian 2020 national security law.

‘Hostile foreign forces’

Beijing has dismissed the protest movement as the work of "hostile foreign forces" who were trying to foment a " color revolution" in Hong Kong through successive waves of mass protests in recent years, and recently appointed hard-line former security chief Zheng Yanxiong, who made his name cracking down on the rebel Guangdong village of Wukan amid a bitter land dispute in 2011, as its new envoy in the city.

The founder and CEO of Art Innovation Gallery, Francesca Boffetti, said she believed the work was removed due to political content.

The work was removed as national security police detained at least six members of a now-disbanded pro-democracy labor union for questioning following the arrest of its co-founder Elizabeth Tang earlier this month, holding them for questioning for at least two days each, according to a post on Tang's Facebook page.

"The national security law was like an ax, and the scariest thing is that many people could be targeted for arrest," Isaac Cheng, a former leader of the now-dissolved pro-democracy party Demosisto now living overseas, told Radio Free Asia.

"The government is also using reasons other than national security to arrest people, which means that anyone still in Hong Kong has to live in fear and censor themselves," he said.

He said the authorities now seem to be going after anyone who could potentially organize others, including former politicians and union leaders like Tang and her husband Lee Cheuk-yan.

He said the authorities recently also revoked bail for veteran rights lawyer Albert Ho, who is awaiting trial on charges of "incitement to subvert state power" in connection with his work organizing now-banned annual candlelight vigils for the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

Cheng said the fact that the national security law applies anywhere in the world makes activists overseas worry that any lobbying work or protests they take part in could bring official retaliation down on the heads of associates still in Hong Kong.

Former pro-democracy lawmaker Nathan Law said he has cut off all contact with previous associates in Hong Kong.

"I haven't been in touch with anyone I used to work with in Hong Kong for nearly two-and-a-half years," Law told Radio Free Asia.

"This is the hope,” he said. “That they won't be put under pressure."

‘Enemies of the party’

Current affairs commentator Sang Pu said it wasn't enough for several high-profile civil society groups to disband, if their leaders remained in Hong Kong.

"In the eyes of the Chinese Communist Party, the organizations may have disbanded, but those people are still there," he said. "These people are seen as the enemies of the party, so it can't let it go."

"They have to keep finding someone to fight against, to ensure that the struggle never ends, and they can keep on generating greater and greater fear," Sang said.

The interrogations of the labor activists came as police announced that Hong Kong's "anti-terrorism" hotline had received more than 14,500 messages from members of the public since last June.

An article in the Hong Kong police publication Offensive said some of the reports involved "threatening messages on social media," adding that police are now considering offering rewards to people who inform on others for suspected "terrorism."

The definition of "terrorism" has been applied to actions not normally seen in that way, including displaying the slogans of the 2019 protest movement. In July 2021, a Hong Kong court convicted motorcyclist Tong Ying-kit of "terrorism" and "secession," handing him a nine-year prison sentence for flying a banner carrying the banned slogan "Free Hong Kong! Revolution now!" at a protest.

Taiwan national security researcher Shih Chian-yu, said the government is misleading the people of Hong Kong about what constitutes terrorism.

"This whole thing is pretty absurd, actually," Shih said. "They are basically using terrorism as a way to force people to inform on each other."

"They call it counterterrorism, but they're actually carrying out monitoring of the population and political purges under that name," he said.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.