At 5 a.m. on a Friday in June, Xiaoqing Li slipped silently out of her bed in Monterey Park, east of Los Angeles. By now, the faintest chirp of an alarm was enough to wake her in the one-bedroom apartment she shared with nine other Chinese migrants she barely knew.

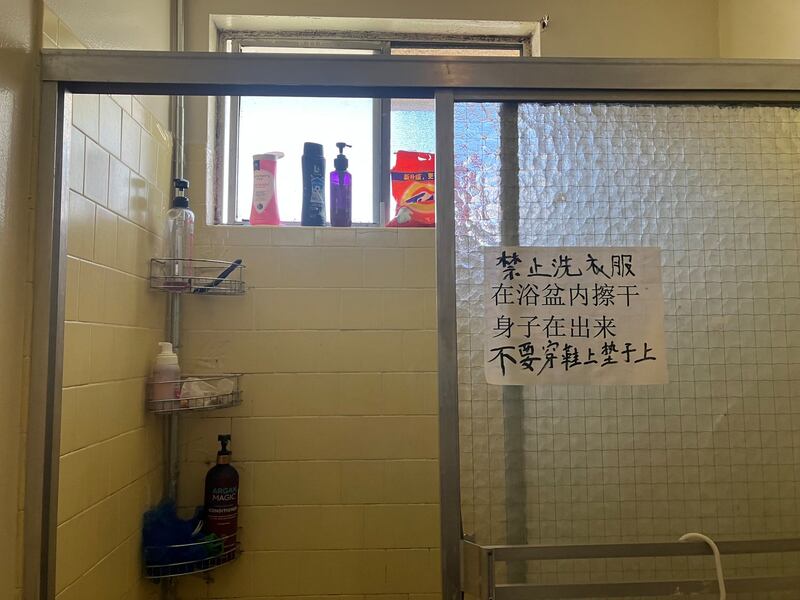

A petite woman whose freckled face looked younger than her 29 years, Xiaoqing tamed her frizzy hair with pins and washed up in the sink, ignoring a roommate’s boxers hanging on the towel rack. She was out the door in 20 minutes to begin a two-hour commute that would take her to a job at a Long Beach warehouse. She wouldn’t arrive back home until past 9 p.m.

Mornings for Xiaoqing have unfurled in much the same way since she arrived in early June after trekking through a perilous jungle in Central America with her 5-year-old son; reuniting with her husband to travel through five countries by bumpy bus; and spending a harrowing day at sea that almost took their child’s life while en route to the U.S.’s southern border.

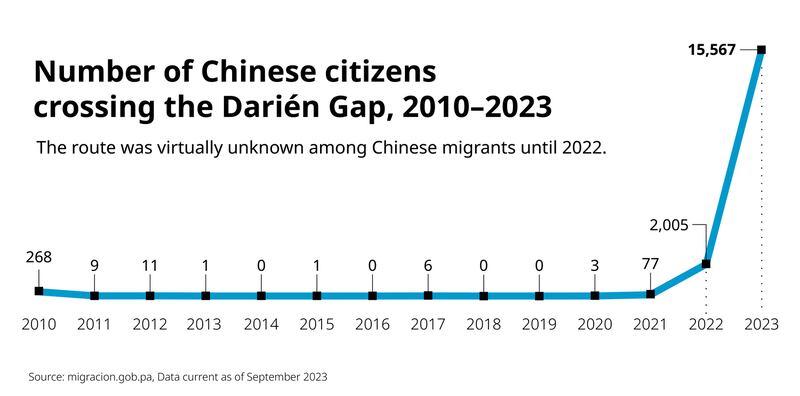

In the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer than 300 Chinese citizens attempted to travel overland through the Darien Gap, a 60-mile roadless jungle between Colombia and Panama where governments, drug cartels and rebels compete for control. But this year alone, more than 15,000Chinese migrants have followed this path.

This journey is known as zouxian (tsou-hsien, or "walk route") in the Chinese community. Driven by growing authoritarianism and a slowed economy back home, migrants rely on social media tips and the hope of building a new life in a new country.

As she boarded bus Line 70 for the long trip to work, Xiaoqing’s phone lit up with an incoming WeChat call. It was her husband, Li, who worked at a marijuana farm two hours to the east of Monterey Park, building greenhouses in the desert. The job paid $3,500 in cash per month and included food and housing, but to Xiaoqing’s chagrin only offered an occasional day off. The separation was made harder by the fact that their son was living with a cousin 30 miles away while the couple tried to work out a more permanent arrangement.

"I'll be back next week. I have a day off," Li said in Mandarin. He asked to be referred to only by his surname.

"Ok, I'll cook something for us."

"How's Maomao?" he asked, using the boy’s nickname.

"He's with his auntie,” she said. “His cough is getting better."

"Good. I have to head to work now. Take care.” With that, he ended the call.

By the time Xiaoqing’s bus dropped her off near City Hall around 6 a.m., downtown Los Angeles was starting to stir. She hustled onto the Metro A-Line for a 50-minute train ride to north of Long Beach. From there, a 15-minute walk brought her to an unassuming warehouse where she labeled packages and earned $12 an hour in cash, below California’s $15.50 minimum. Migrants have to wait at least 150 days after submitting their asylum case before they can apply for a work permit. Without such papers, off-the-books jobs were the best Xiaoqing and Li could hope for in the meantime.

As Xiaoqing worked, tracing the contours of toys and electronics passing through her hands, she recounted her journey in hushed tones, speaking matter of factly about how she trudged through a rainforest, nearly lost her son and was extorted for money by corrupt police in Mexico. She counts her family fortunate for having made it to the U.S. safely, but wishes they could remain together.

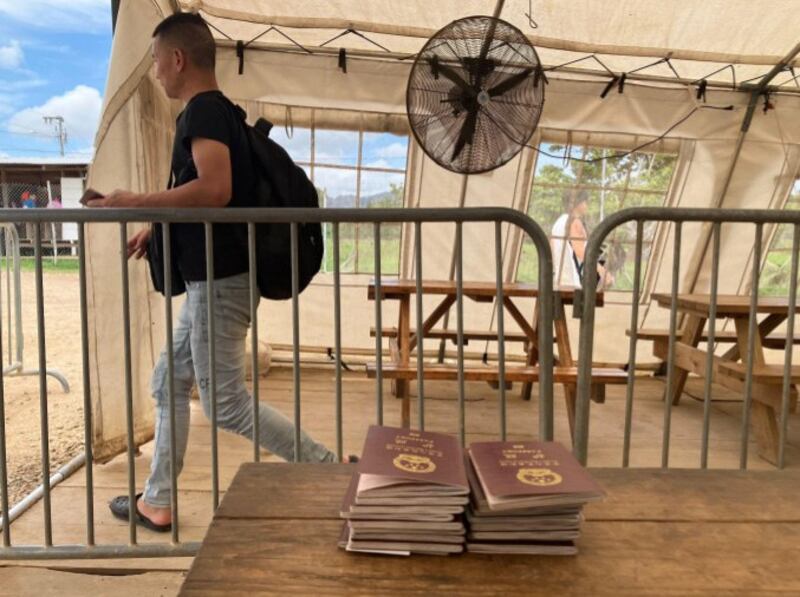

Monterey Park has for decades been a starting line for immigrants from China who arrive with limited English and a few hundred dollars in their pockets. Largely through word of mouth in the tight-knit Chinese community, they secure temporary shelter in group homes (jiating lüguan, or “family hotels”) that charge as little as $10 a day but cram as many people as possible into limited space. The migrants seek whatever jobs they can find — in restaurants, warehouses, massage parlors — while they await their American dream to take shape in a system that offers scant legal avenues beyond the uncertain gamble of asylum.

For Xiaoqing’s family, however, the path to that dream had come at the price of separation, since her group home didn’t allow children to stay overnight and Li hadn’t managed to find a job anywhere nearby.

While Li insisted his distant work was worth the separation, Xiaoqing had spent enough time being apart. When Maomao was just learning to walk in 2019, she left him with her parents in rural Hubei, a landlocked province in central China. This allowed Xiaoqing and her husband to pursue jobs in larger cities, a scenario common among China's migrant workers.

But now that they had made it to the U.S., she wondered why they were still in the same situation.

“I’m fine with being separated temporarily, as long as there is a reunion to be expected,” Xiaoqing said. “Otherwise, what’s the point of having a family?”

Runology

Frustrated by three years of the Chinese government’s stringent zero-COVID policies and skeptical about future opportunities, many Chinese citizens have begun to consider leaving. Since the April 2022 lockdown of Shanghai, online searches for “run,” a euphemism for emigration, have skyrocketed in China. But with tightened visa rules in recent years, the route that some of Xiaoqing’s distant family members once took — entering the U.S. on a tourist visa before filing for asylum — has largely become inaccessible to people like her.

In the 2019 fiscal year, 82% of Chinese citizens seeking U.S. tourist or business visas were approved. By 2021, the approval rate plummeted to 21%. The drop is largely attributed to a Trump administration policy that barred people traveling from China without U.S. citizenship or permanent residency from entering the country.

Although the approval rate rebounded to 70% last year, the U.S. issued just under 70,000 tourist and business visas to Chinese citizens — down from more than 1 million in 2019. While much of the decrease is related to China's COVID-era travel restrictions, which were lifted only in late 2022, experts suggest it could also be due to the U.S. embassy and consulates giving fewer visa appointments than before.

As visas become harder to obtain, the “walk route” to the United States has increasingly become more popular in China, the fourth largest source country for migrants traversing the Darien Gap this year.

Last summer, while using a VPN to browse the blocked website YouTube, Li came across a vlog of a Chinese migrant traveling atop "La Bestia." The notorious freight train carries thousands of migrants to the U.S. border each year, many of whom cannot afford a bus ticket let alone the cost of smugglers to ferry them across the whole of Mexico.

Something clicked for Li, who previously made $640 a month working at an iPhone factory in Wuhan but had struggled to find stable employment since being laid off shortly after the start of the pandemic.

“If it works out for us, my kid can grow up in a free country,” he recounted a year later in an interview. “He won’t have to slave away like we did in China.”

While her husband was captivated by the American dream, it was Xiaoqing who ensured the family had a tangible plan. She spent months scrolling through Twitter and lurking in Telegram channels. As fellow Chinese migrants shared tips from their journey on the internet, Xiaoqing took detailed notes — from where to exchange money in Colombia, to the contact information of smugglers in Mexico, to everything she could learn about that daunting rainforest in between.

“I’d do whatever I can to keep my family safe,” said Xiaoqing. It was only once the journey started that she realized how little control she had over that.

A risky path

The Darien Gap was once deemed such a perilous migration route that few dared to traverse it. But amid the pandemic and instability in countries such as Venezuela and Haiti, the number of migrants and asylum seekers has surged. Last year, close to 250,000 people trekked through the jungle. As of September this year, the number has hit a record high of 400,000. Most making the crossing come from Latin America, but they have been joined in increasing numbers by those from China, Afghanistan, India and dozens of other nations.

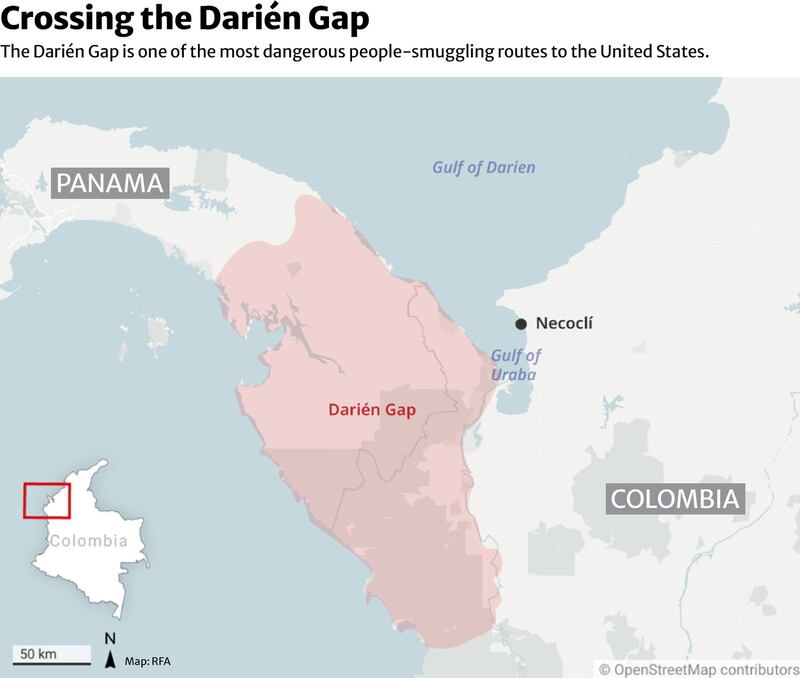

To embark on the journey, Xiaoqing and her family flew from China to Thailand, and then to Ecuador, one of the only South American countries that Chinese citizens can visit without a visa. From there, thousands of migrants and asylum seekers like Xiaoqing begin their overland trek north.

On the day the family landed in Quito, Ecuador, Li shared a post in Chinese on WeChat to show his determination. "A destination sought after by many may not be heaven, but a place that everyone wants to leave behind is a living hell for sure."

They took a bus to the Colombian border town of Necoclí, joining hundreds of migrants who waited for boats to take them to the jungle's entrance. A chilling rumor rapidly circulated: a Chinese woman, not much older than Xiaoqing, died on the dangerous passage. The news weighed heavily on Xiaoqing, a stark reminder of the unpredictability of their journey to a new life.

“My mom used to take me to church when I was little. I never paid much attention,” Xiaoqing said. But she closed her eyes to pray as she set off for the five-hour boat ride with her son in her arms. “I beg for your blessing.”

To navigate the jungle, Xiaoqing paid roughly $1,500 to secure a guide, a porter and a horse for herself and her son. Her husband, aiming to save money, spent $500 to go on a path that required a longer and more difficult trek on foot.

When Li emerged from the other side of the jungle four days later, he was severely dehydrated. His phone had been damaged during a river crossing and lost the use of Google Translate, which had been essential to communicate with his guides and migrants who spoke Spanish. On the final day of his journey, Li went without a sip of water.

Yet he persevered, helped by fellow migrants from South America who shared food with him. Assisted by the National Border Service of Panama, Li then found Xiaoqing and their son at a makeshift camp where medics treated migrants for injuries. After two days of recovering, the family began making their slow way via a series of buses across Central America to the southern border of Mexico.

Despite expectations that President Biden would reverse or ease his predecessor's border policies, the U.S. has continued to pressure Mexico to deter people from heading north. Mexico, in turn, has cracked down on unauthorized migration. In 2022, its apprehensions of migrants reached an all-time high of nearly 450,000. This June, the government again reported a record number of apprehensions. Once taken into custody by the Mexican authorities, migrants can face prolonged detention in abusive conditions.

Xiaoqing described Mexico as “hell mode.” While trying to head north from the state of Chiapas, the family was stopped twice by Mexican authorities and forced off their bus. They bribed the police to avoid detention. On their third attempt, Xiaoqing hired a smuggler, a Mexican man recommended to her by other Chinese migrants. He promised to arrange a 10-hour boat ride to bring them closer to the southern U.S. border.

Setting off before dawn, the family found themselves on a small motorboat on the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean. Their clothes were soaked, and Maomao caught a chill. As he began to cough, Li cradled him and wept.

"He never complained, not even once," Li said. "That's what broke my heart."

As the boat neared the shore, a fellow migrant tried to help Maomao disembark by grabbing the boy's life jacket. But the jacket was too big and he fell through, plunging into the ocean. Xiaoqing screamed. In a split second, Li dove in after their son and held him up to Xiaoqing, who quickly pulled Maomao back onto the boat. Choking on the salty water and with mucus streaming from his nostrils, the boy was too traumatized to cry.

After the harrowing boat ride, the family borrowed money from a fellow Chinese migrant to hire another smuggler who helped them cross the southern U.S. border.

In total, the journey from China to the U.S. cost $20,000 — their life savings.

A distant dream

During her nearly two-month journey, Xiaoqing cried just once. On the first night after she set foot on U.S. soil in Arizona, Xiaoqing’s parents appeared to her in a dream. She was back in their old courtyard in rural Hubei. While Xiaoqing helped her mother set the dinner table, her father held Maomao in his arms.

In an instant, both her father and son vanished from the dream. Jolted awake, Xiaoqing was pulled back into reality by the harsh glare of fluorescent lights in the immigration detention center. She found herself within the confines of a makeshift room, its boundaries delineated by semi-opaque plastic sheets hanging from a steel frame. More than a dozen people, mostly women and children from Latin America, curled up on thin mattresses haphazardly scattered on a cold, hard floor. Beside her, Maomao was sound asleep, his small body wrapped in a mylar foil blanket that made a sharp, metallic sound whenever he shifted in his sleep.

Xiaoqing gently tucked in her son and wept.

Once in the U.S., immigrants must apply for asylum for a chance of legal residency. But whether the request is granted can come down to the judge assigned to the case. At the U.S. Immigration Court in Los Angeles, where Xiaoqing's case is pending, denial rates for asylum cases range from 32.6% to 96%, according to data compiled by Syracuse University. Nationwide, fewer than half of asylum applications are approved.

"The outcome of one’s case is heavily influenced by the judge they are assigned to. Some judges, especially those with law enforcement backgrounds, tend to be stricter with asylum cases,” said Jiawei Peng, a California-based lawyer specializing in deportation defense. “Others might be more sympathetic. But generally, there is minimal oversight."

Historically, Chinese asylum seekers have enjoyed a higher approval rate than those from many other countries. From the fiscal year 2001 to 2021, 67% of asylum applications from Chinese citizens were granted. However, most of these asylum seekers entered the U.S. on a visa, unlike Xiaoqing and her family.

The family is set to appear for an immigration court hearing in February 2025, and a final resolution might take many more years. In the meantime, they cannot visit China without jeopardizing their asylum application.

Xiaoqing recalled how Maomao used to love playing with his grandfather in the family courtyard. Now, she mused, “I wonder if my son will ever be able to see his grandparents again."

Glimmers of hope

In early July, Xiaoqing hoped to convince Li to rent a bed in her group home and work in her warehouse, which she said had a nice manager who didn’t ask for employment authorization. She took a rare day off work to cook him a spicy pork belly dish, a recipe of her mother’s that worked magic whenever she had any persuading to do.

At the dinner, however, Li wasn’t entirely convinced by his wife’s arguments. His pay may have been little better than her warehouse, but a bed in the group home would cost $400 each month, not counting expenses for food — both of which were covered on the farm.

The couple remained separated with little chance of reuniting soon. Since arriving in California, they had seen their son just twice. Because neither of them had a car, visits with Maomao depended on the availability of Xiaoqing’s cousin to drive the boy for an hour each way. Li's schedule rarely coincided with Xiaoqing’s, who spent her weekly day off shopping and speaking with her parents back home.

"Despite how hard the journey was, at least our family was together," she said at the time, one of the only moments she expressed any real frustration at her current situation. "But now, it feels like I can't see the light at the end of the tunnel."

Two months later in September Xiaoqing sounded lighter in a phone conversation, even though she was not yet reunited with Li and Maomao. With so many new arrivals competing for jobs, Li had failed to find a position closer by. But he had left his arduous farm work for an easier warehouse job. And the couple was hoping they would have a better chance at finding work near each other once they obtain papers in the coming months.

Xiaoqing said she had settled into a routine that includes walks around the neighborhood when she has time. A few weeks ago, she stumbled upon a hopeful scene: a Chinese family moving. As the husband directed the movers, the wife cradled a little girl in her arms and an older boy dashed around giggling.

Among the discarded furniture that littered the roadside, Xiaoqing noticed a chair cushion that looked new. She picked it up and brought it back to her shared room, adding an element of comfort to her new life in the U.S.

“I’d like to rent a place of our own before we submit our work permit applications in December,” Xiaoqing said. “With the right papers, I hope my husband can find a job closer to us.”

She recounted a recent afternoon spent with Li and Maomao, just the second time the family had been together since their arrival. They went to Santa Monica beach and the Hollywood Walk of Fame, where Maomao bragged about his accomplishments in kindergarten.

When he told her his teacher said he was best, Xiaoqing asked "best at what,” and the boy joked: “best at finishing my meals on time.”

“I hope he stays this way, always happy and worry-free,” Xiaoqing said. “As long as he enjoys life in America to the fullest, it’s all worth it.”

Edited by Abby Seiff and Jim Snyder.