Chinese students studying abroad report widespread fear that activities their peers take for granted – like attending vigils or openly discussing political views in class – could get them and their families back home in trouble, according to a report released Sunday from Amnesty International.

The London-based human rights group interviewed 32 students across eight Western Europe and North America countries from June 2023 to April 2024. One-third of those interviewed reported living in a “climate of fear” that had altered their academic experience.

Ten of the students said Chinese authorities had visited family members back in China to discourage their campus activities, in some cases with a remarkable swiftness that added to the students’ sense of unease.

“Rowan” (the report used pseudonyms) said her father called just hours after she attended a commemorative event for the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, even though she hadn’t registered for the event or posted anything online about her participation.

Her father was told to remind his daughter not to do anything that would put the Chinese government in a bad light.

The underlying message, Rowan told Amnesty in a 2023 interview, was that “you are being watched, and though we are on the other side of the planet, we can still reach you.”

An email to the Chinese Embassy in Washington asking for a response to the Amnesty report had not been returned by press time.

A fear of peers

There are 900,000 Chinese students studying overseas, according to Amnesty International. Nearly 290,000 Chinese students were granted visas to study in the United States in fiscal year 2023, according to the State Department. China sends more students to the U.S. than any other country.

News outlets including Radio Free Asia have reported on several cases of “transnational repression” by China against students in the United States who took part in protests or other activities unaligned with Communist Party thinking.

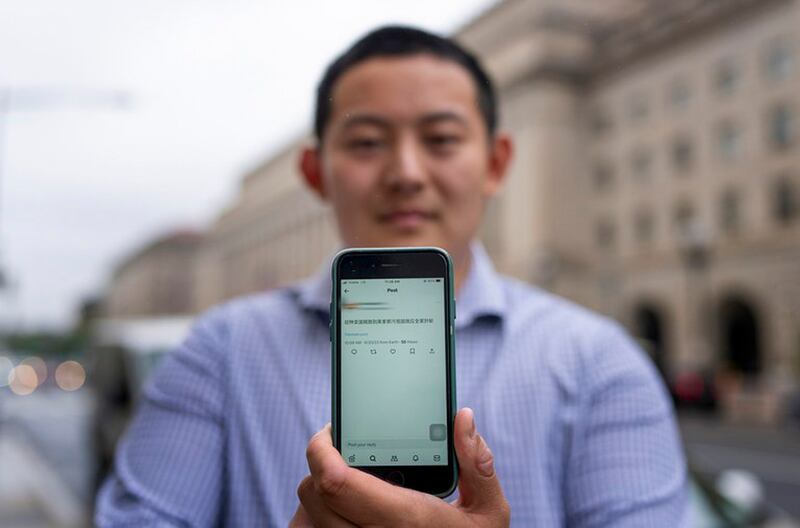

Zhang Jinrui, a law student at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., told RFA last fall that state security officials in China visited his family after he took part in "white paper" protests that sprang up across the globe in opposition to harsh anti-COVID policies and restrictions on free expression in China.

Chinese students at Columbia University who were trying to start a student group in support of the white paper protests back home talked to RFA about the various precautions they were taking to avoid getting themselves or their families in trouble.

They wore masks at events and were wary of inviting Chinese students they didn’t know to participate for fear of being reported to authorities.

One-half of the students who Amnesty International interviewed said they were fearful that fellow students would report on them. This fear compounds a sense of isolation and loneliness for students already dealing with the struggles of living in a foreign country, Amnesty said.

Michael, a student in North America, told Amnesty that “he was ostracized, removed from online chat groups and kicked out of a community hobby club” after the local Chinese community learned about his involvement in political protests.

Edited by Malcolm Foster.