For yet another year, there was “little to no meaningful progress towards curbing corruption” in Asia in 2023, according to the latest annual graft index from Transparency International, with only three regional jurisdictions making it into the world top 20.

Singapore (5th), Hong Kong (14th) and Japan (16th) remain the jurisdictions with the most "clean" government in Asia, according to the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index, which was released Tuesday.

Ahead of Singapore on the list, the top four countries remain Denmark, Finland, New Zealand and Norway, rendering the top five unchanged from last year. The United States, meanwhile, comes in at 24th, tied with Barbados and just ahead of the Himalayan nation of Bhutan.

"Very few countries show sustained turnarounds that indicate significant changes in corruption levels, and several historically at the top are slowly declining," the report says of Asia, adding it was "another year of little to no meaningful progress towards curbing corruption."

The annual report draws on "several different sources that capture perceptions among businesspeople and country experts" of corruption, Transparency International says. The group then calculates a score out of 100 for each country and ranks them on a list from 1 to 180.

Stuck in the mire

It’s the fifth year in a row that Asia’s overall average score has been stuck at 45 out of the possible 100, the group says. But it’s worse than that: 71% of Asia-Pacific jurisdictions fall below that dismal mean, with a steep drop-off on the list after the region’s best performers.

In fact, after Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan and Bhutan, the next "cleanest" Asian governments are in Taiwan (28th), South Korea (32nd) and Malaysia (57th). Each of those three were little changed from last year.

East Timor and mainland China (joint at 76th) then lead the region mid-table on this year’s list – beating out Vietnam (83rd), India (93rd), Thailand (108th) and Indonesia and the Philippines (115th).

It was a slight fall for Vietnam, after it improved from 87th to 77th place in last year’s report. China in 76th place is a more notable fall, though, after it came in at 65th last year and the year before that was at 66th.

That puts the world’s second-largest economy back in the corruption territory it occupied in the late 2010s – although it’s still not as bad as 2018, when China came in at 87th, behind Turkey and Argentina.

At the worst end of this year’s list are Laos (136th), Cambodia (158th) and Myanmar (162nd), which in the region beat out only North Korea (172nd) for perceptions of corruption in the public sector.

Asia has little to cheer for at this end of the list, with those countries only beating out war-torn or economically ravaged countries like Yemen (176th), Syria and Venezuela (177th) and Somalia (last).

Authoritarian link

The report’s authors’ note that the bottom of the index is mainly “fragile states with authoritarian regimes” and draw a direct connection between illiberal and undemocratic regimes and poor scores.

“These weak scores reflect the lack of delivery by elected officials on anti-corruption agendas, together with crackdowns on organised civil society and attacks on freedoms of press, assembly and association,” Transparency International says of the Asia-Pacific in the report.

Myanmar, for instance, has fallen 32 places since it peaked at 130th in the 2017 report. It has fallen back behind Cambodia as Southeast Asia’s most corrupt jurisdiction for a second year in a row, after beating Cambodia for an unbroken seven-year stretch from 2013 to 2020.

Perhaps not coincidentally, that stretch coincides with a now aborted period of democratic reform in the country: Myanmar held its first free elections in decades in April 2012, allowing Aung Sang Suu Kyi's party back into government, but returned to outright authoritarianism and a bloody civil war after the February 2021 coup d'etat by the military.

The report also notes that many countries have pursued “short-term fixes” to corruption that focus on punishing officials caught engaging in graft, rather than investing in what it calls “integrity infrastructure” – reforms that put in place long-term structural checks on power.

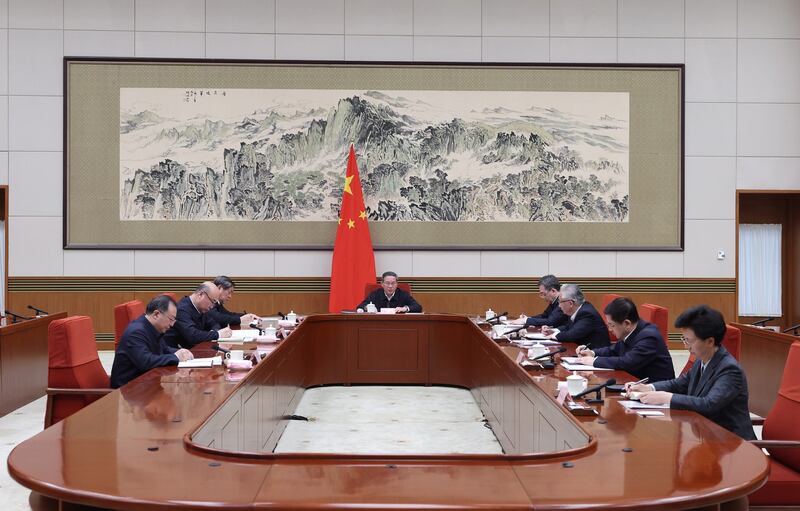

It notes China has "made headlines with its aggressive anti-corruption crackdown," punishing more than 3.7 million officials over the past decade, which coincides roughly with the time since President Xi Jinping came to power pledging to crack down on corruption.

“However, the country’s heavy reliance on punishment rather than institutional checks on power raises doubts over the long-term effectiveness of such anti-corruption measures,” it says.

Since Xi assumed the presidency in 2013, China has improved just four places on the annual graft index, going from 80th to 76th.

Edited by Malcolm Foster.