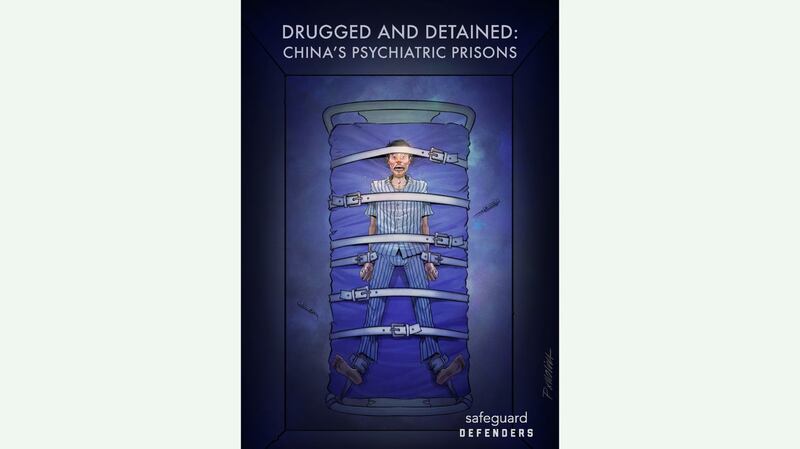

Police and government agents in China continue to lock up government critics in psychiatric hospitals despite 'reforms,' according to a new report from human rights group Safeguard Defenders.

"These legal reforms have absolutely not worked," the group said in a statement launching its new report into being "mentally illed," an online slang term used to indicate forcible commitment to a psychiatric facility, a method often used by the authorities to silence dissidents, petitioners and other activists.

"Police and government agents continue to arbitrarily send petitioners and activists, sometimes repeatedly," it said, adding that one woman interviewed for the study had been sent 20 times.

The incarcerations take place both at general medical facilities, and within the network of police-run Ankang hospitals designed to house criminals and suspects with mental health conditions.

"Doctors and hospitals are either coerced by, or collude with, the authorities by allowing this abuse to take place," the group said.

While a new Mental Health Law banned the committal of psychiatric patients without a medical assessment, and an amended Criminal Procedure Law stepped up judicial oversight requirements where police commit people to psychiatric care, little has changed on the ground, according to the report.

"Once inside, victims may stay there for months, even years," Safeguard Defenders said. "Nine victims have been inside for more than 10 years. Others have been locked up again and again."

Serious physical and psychological trauma

Nearly one third of the 99 victims interviewed said they had been incarcerated in this way at least twice.

"Many patients were physically and mentally abused," the group said. "They were subjected to painful electroconvulsive therapy, often without anesthesia; tied to their beds where they were left for hours to lie humiliated in their own waste; and beaten and isolated."

People locked up for "mental illness" are also denied contact with family members or lawyers, even by phone call, it said.

And their problems aren't over once they do get out, with victims suffering "serious physical and psychological trauma" including dramatic weight loss, scarring and muscle wastage from neglect and mistreatment.

"The forced medication has also left enduring mental scars including signs of dementia in even young victims, night terrors, tremors and suicidal thoughts," Safeguard Defenders said.

The group called on the international community to "once again pay attention to this grave abuse of human rights," and on the Chinese government to end the practice and shut down Ankang hospitals.

U.S.-based legal scholar Chen Guangcheng said enforced psychiatric "treatment" is frequently used to target dissidents, petitioners and rights activists.

"The CCP has been using the claim that they are mentally ill on petitioners for a long time now," Chen told RFA. "If they can't suppress them with interception and detention ... they do this instead."

"The police have the power to decide whether you are sick, and decide to send you to a psychiatric hospital, and even to decide the diagnosis they give you," he said. "The diagnosis is tailored by the hospital to suit the needs of the CCP, so human rights defenders can be detained and persecuted at will."

'No checks and balances'

Chen said the changes to the law had made little difference.

"It doesn't matter how well drafted a law is: if there are no checks and balances on its implementation, then it's useless," he said.

Rights lawyer Wang Yu said she had represented a client in the northeastern city of Harbin 10 years ago in a similar case.

"Some of these dissidents, petitioners, and human rights defenders haven't broken the law at all, but have been declared mentally ill and held in a psychiatric hospital, with no due process or approval needed from the authorities," Wang said.

"It's a particularly egregious method," she said.

Huang Yong, son of Sichuan-based rights activist Huang Dingbin, said similar treatment had been meted out to him and to his father.

"My father was detained on Sept. 5, 2008 and held for 43 days in a psychiatric hospital," Huang told RFA. "Basically, we were standing up for our rights and petitioning."

"I was sent to [a psychiatric hospital] for nine days in 2013, in 2016 and in 2017," he said. "Both my father and I were detained many times."

"My father went to Chengdu to petition about a grievance in 2008, reporting a case to the [CCP's] Central Commission for Discipline Inspection," he said. "They locked him up in there. They now call it a healthcare service provider."

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.