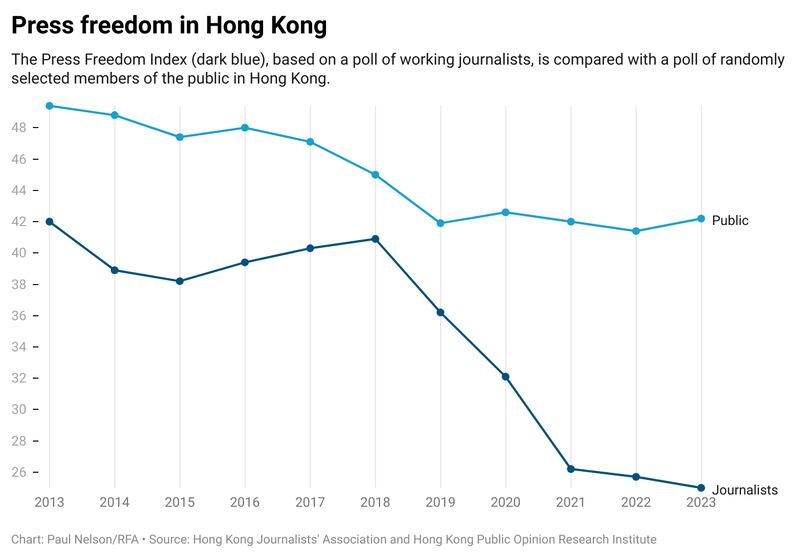

Press freedom in Hong Kong has fallen to its lowest point since an annual survey of the city's journalists began 11 years ago amid fears it will weaken still further in the wake of Article 23 security legislation passed in March.

More than half of journalists who responded to the latest Hong Kong Journalists' Association survey said press freedom had declined over the past year, with more than 90% of respondents saying that press freedom had declined overall for the fifth year in a row.

The Press Freedom Index, carried out with the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, received completed survey questionnaires from 251 working journalists between March and May 2024, polling their opinions about the level of press freedom.

A poll of 1,000 randomly selected members of the public showed little perceived change from the previous year, however.

"Journalist respondents were highly concerned about the potential impact of Article 23 national security legislation — introduced in March 2024 — on the media in Hong Kong, with more than 90% saying this would significantly impact press freedom in the city," the association said in a statement on its website.

Jimmy Lai

Press groups have expressed concern that the language in the law around sedition and state secrets is too vague, and could be interpreted to cover actions or speech by journalists.

Many cited the case of Next Digital media mogul Jimmy Lai, who is currently standing trial on two counts of "conspiracy to collude with foreign forces," one count of "collusion with foreign forces" under the 2020 National Security Law, which ushered in a citywide crackdown on public dissent in the wake of the 2019 protests.

Much of the prosecution's evidence centers on opinion articles published in Lai's now-defunct Apple Daily newspaper.

Lai has been an outspoken supporter of the pro-democracy movement, and several editors at his former paper are also awaiting sentencing for calling for international sanctions in columns and opinion pieces.

The 2020 National Security Law and the Article 23 legislation were also in the top five factors affecting journalists in Hong Kong, the survey found, while respondents also cited the disappearance of South China Morning Post journalist Minnie Chan on assignment in Beijing and the sacking of the political cartoonist Zunzi by the Ming Pao newspaper.

Association chairperson Selina Cheng, who was fired from her job at the Wall Street Journal for running in elections to lead the union, said there was a gap between the public perception of press freedom and journalists' experience of it when doing their jobs.

"The public mostly notices the finished product ... and may not consider self-censorship," Cheng said. "And if journalists have concerns while reporting, writing or editing, the public may not know about it, but the journalists do."

Current affairs commentator Johnny Lau said the process had been one of "gradual compression" on journalists.

"The general public wouldn't notice that as a sudden thing like a needle prick, but instead gradually adapts to the pain," Lau said. "The government's approach is subtle, and reduces the public's demand for information, which is actually a way to hide things from the people."

Cheng said she isn't optimistic that things will change any time soon.

Vague wording

The " Article 23" Safeguarding National Security law passed in March includes sentences of up to life imprisonment for "treason," "insurrection," "sabotage" and "mutiny," 20 years for espionage and 10 years for crimes linked to "state secrets" and "sedition." It also allows authorities to revoke the passports of anyone who flees overseas.

Officials in China and Hong Kong say that journalists are safe to carry out "legitimate" reporting activities under both the 2020 National Security Law and the Article 23 Safeguarding National Security Law, which was passed on March 23.

Yet the wording of the laws is vague, leaving journalists trying to read between the lines of official denunciations and legal rulings to figure out where the boundaries lie.

Getting it wrong can get a journalist censored, fired, or sent to jail.

Since the Press Freedom Index was founded in 2013, there has been a clear downward trend in the ratings of both the public and journalists, the Association said, adding that the journalists' score has plummeted from 42 to 25 in the past decade, while the public score fell from 49.4 to 42.2.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.