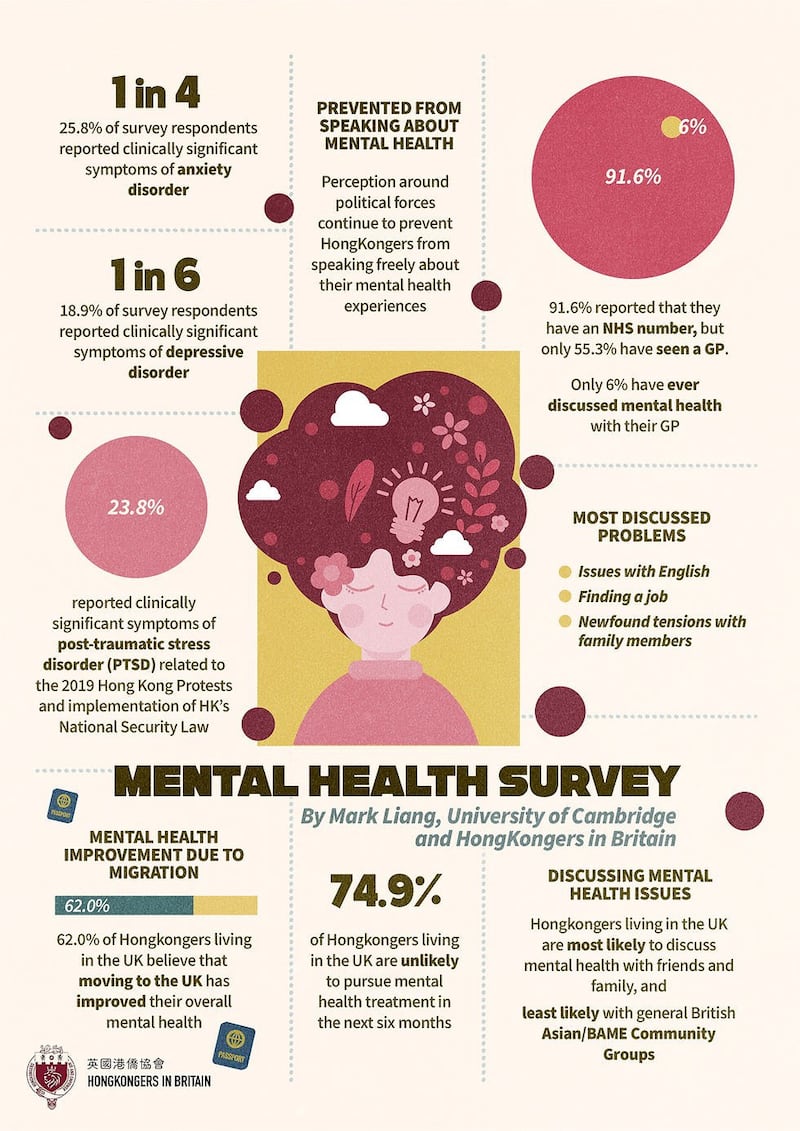

Nearly one in four Hongkongers who fled an ongoing crackdown by the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) say they still suffer from symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) linked to the violent crackdown on the 2019 protests and the subsequent fear engendered by the national security law, according to a recent survey.

A survey of recently arrived migrants by the Hongkongers in Britain group found that 23.8 percent of respondents reported symptoms of PTSD linked to the 2019 protests and subsequent political crackdown.

Nearly 19 percent reported symptoms of depression, while 25.8 percent reported symptoms of anxiety disorders, it said.

The survey found that issues with English, jobhunting and newfound tensions with family members were among the most commonly reported problems affecting the mental health of recently arrived Hongkongers.

"Mental health issues ... included perceived fear of retribution for discussing politics and worry for people still back in Hong Kong," the report said.

"Perceptions around political forces continue to prevent Hongkongers from speaking freely about their mental health experiences," it said.

University of Cambridge mental health expert and survey author Mark Liang said the majority appeared reluctant to seek professional help, however, preferring to talk to friends and family, whom they trusted, amid fears of retaliation against loved ones who stayed behind.

"[Even Hong Kong mental health professionals in the UK] stated that it's very difficult to get people to come in as patients," Liang told a news conference presenting the report. "They said that even after developing trust ... even after talking about things that weren't related to PTSD, like about coming into the country and immigration, when they started probing questions like where were you in 2019, a lot of Hongkongers wanted to just freeze up."

"That has to do ... with this perception that we believe Hongkongers have of the political situation ... it's choking out many Hongkongers from speaking honestly and freely about their experiences, which is very important in the healing process," Liang said.

Drastic drop in freedom

Since the CCP imposed a draconian national security law on Hong Kong, saying it was necessary to prevent a "color revolution" instigated by "hostile foreign forces," freedom of expression has declined sharply, with dozens of former opposition politicians arrested for subversion, several pro-democracy media outlets forced to close, rights groups forced to disband and student unions ousted from university campuses.

After the law took effect on July 1, 2020, national security police set up a hotline to encourage people to inform on people "suspected" of having breached its sweeping bans and prohibitions, which include protest slogans, commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen massacre and any other form of peaceful criticism of the authorities.

The U.K. rolled out a new pathway to citizenship for some three million holders of its BNO passport and their families, and more than 97,000 applications have so far been successful, the Home Office said in March 2022.

Migrants from Hong Kong are suffering from the emotional upheaval of moving, sometimes at short notice, to an entirely new country with their families, and cited problems helping their kids to settle in new schools as a major issue affecting their mental health, Liang said.

There is also the feeling that an essential part of their identity has been lost.

"A part of myself is not there when I do not speak Cantonese... even though English is my better [academic] language," one respondent told the survey.

Others cited "survivor's guilt" as weighing heavily on their emotional state, while others felt the pain of being exiled from their home for reasons beyond their control.

“I hate to think [I] cannot travel back to [my] homeland freely, no one wants to be exiled or named fugitive," the report quoted another respondent as saying.

Asylum seekers' quandary

But asylum-seekers are even more vulnerable than BNO passport-holders, given the high degree of uncertainty that comes with applying for refugee status, Liang said.

"Asylum seekers coming into this country have a much, much different experience than BNO passport-holders. They are required to present information that suggests they are a refugee who would be at political risk if they went back to their country of origin," Liang said.

"They are not given the same freedoms as in the right to study, to work, to live as a BNO holder, and that of course is very impactful on one's mental health, just having that uncertainty ... asylum cases in the U.K. right now are backlogged by months," he said. "One asylum-seeker [described it as] political and social limbo."

But the report also said that the majority of respondents to the survey had reported an improvement in their mental health since leaving Hong Kong, despite the difficulties.

And those who were struggling were more likely to seek out friends or family.

"There are ... other reasons, outside forces besides culture that are preventing people from seeing mental health providers in the U.K.," Liang said.

Meanwhile, a court in Hong Kong jailed a 26-year-old man accused of being the admin of the SUCK Telegram channel, to six-and-a-half years' imprisonment.

IT worker Ng Man-ho was found guilty of allowing posts to the channel from October 2019 to June 2020 that allegedly taught people how to make home-made explosives, set up barricades and encouraging people to take part in the student defense of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), which was hit by around 1,000 tear gas rounds from Nov. 11-15, 2019.

During the siege, students set up barricades to prevent riot police from entering the campus, as President Rocky Tuan and other senior members of staff tried to negotiate with police to defuse the standoff by standing down.

As tensions worsened, officers opened fire with tear gas and rubber bullets towards Tuan, staff members and a large group of students surrounding them, saying he should leave if he had no control over the black-clad protesters guarding the bridge with barricades, fires and by lobbing petrol bombs and bricks.

Ng was accused of using posts to the Telegram channel to encourage and teach such practises, and was charged with "conspiracy to incite others to commit arson, riot, manufacture explosives and cause grievous bodily harm with intent," among other charges.

He was also accused of inciting people to deploy toxic chlorine gas in police stations and subway stations, although no such attack appears to have occurred.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.