HONG KONG—China's Huai River basin—an intricate network of rivers, lakes, and fishing villages—has been the subject of poetry and music for generations, stimulating the popular imagination with scenes of rural peace and plenty by its rippling shores.

But since China's economic miracle came to the region in the late 1990s, the Huai River has been reduced to a toxic mess by industrial effluent from businesses along its banks, and some of its formerly idyllic villages now have cancer rates at least 10 times higher than they were three decades ago, according to local residents and environmental activists.

A local resident, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the rate of cancer between 1990 and 2005 in the central province of Henan's Huangmengying village population of 2,500 is much higher than the official count of 116 cases.

"I can't tell you what it actually is. If I do, I'll get myself in a lot of trouble," he said.

The villager said "hundreds" had died of cancer over the fifteen year period, adding that 200-300 was a "conservative" estimate.

Another Huangmenying resident said he had lost two close family relatives of different generations to cancer in recent years.

"A wart grew on my mother's face, and then it became cancerous," Huang Hailian said.

"[My wife] has lung cancer. Four years ago, she was receiving treatment in a health clinic. She threw up a lot of blood one day. They sent her to Huaidian and as soon as she was examined, they found she was already in the advanced stages of cancer," he said.

Huanmengying village government chief Wang Linsheng declined to provide exact figures, but said the rate of cancer in the village had decreased significantly in recent years.

"Ever since the government constructed deep wells, there's been a substantial decline in the incidence of cancer," Wang said.

"According to incomplete statistics, there are probably still about a dozen cancer patients," he said.

'Tons of waste'

The Huai River basin covers Henan, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Anhui provinces, and is one of the most densely populated areas of China.

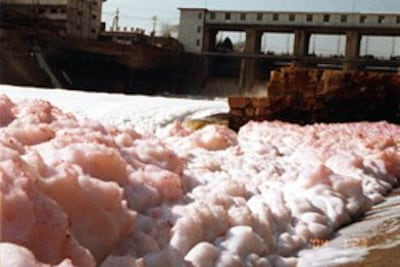

According to China's State Environmental Protection Agency [SEPA], "millions of tons of waste and urban sewage have poured into the river for years."

A U.S. $2.4 billion clean-up program began in 1994, but environmental officials say progress has been slow and polluters have largely failed to comply with regulations.

SEPA blames the paper-making, chemical, beverage, textile, and food industries for discharging more than 70 percent of the river's total chemical oxygen demand (COD), and more than 90 percent of the ammonia nitrogen, found in its waters.

The introduction of fertilizer into the river from farming run-off has also risen sharply in recent years.

Huangmengying government chief Wang credits former press photographer Huo Daishan with bringing the poisoning of the Huai River villages to the attention of the public.

"Huo Daishan deserves 95 percent of the credit. Although the government provided investment, if there were no Huo Daishan, this village wouldn't have tap water to drink," Wang said.

"He was mainly creating propaganda because that's the only way to attract attention," he said.

Poisonous fumes

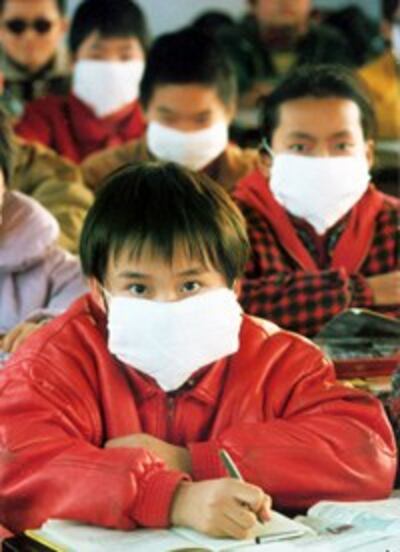

Huo, who grew up on the river basin, said he first became aware of the severity of the pollution after he went to his hometown of Huaidian on a reporting assignment and found local schoolchildren wearing gas masks in the classroom.

"I wanted to shoot pictures of a school, but you'd have to take masks into class with you," Huo recalled. "It’s next to a watergate, so I went over to look at the school’s situation and condition of the river. I noticed there were a lot of dead fish, and the water was dark and smelly."

Huo said he was unable to continue working because of poisonous fumes, but returned later to shoot pictures wearing his own gas mask.

He said the scene was a far cry from a popular Chinese ballad of the 1950s, which refers to a "great river of vast waves, with the wind blowing the fragrance of rice paddies to the shores."

Huo became more personally affected by the river's pollution when Ni Anmin, his childhood friend and the late mayor of Wangdian township, died of cancer.

On his deathbed, Ni told Huo he supported his continued fight for a clean-up of the Huai River, saying: "I'm dying. My body's not well. I’m not going to make it, but you have my support."

"He also told me: 'You're different from other reporters. You grew up in our local community. Who’s going to speak for us if you don’t?' He then died from illness shortly after. So, I didn't hesitate, and I've been doing it ever since," Huo said.

Huai River Defenders

Huo, who lost his mother to cancer, started a nongovernmental organization called the Huai River Defenders in 2003. The group has had some success in making local industry pay more attention to pollution.

According to writer Chen Guidi, author of Warning from the Huai River, Huo began his campaign at a time when there was relatively little official support for the issue.

"At that time, the national news media wasn't looking at these kinds of things," Chen said.

"Apart from our State Environmental Protection Agency newspaper, The China Environment, they regarded it negatively. So reports about pollution were rarely ever seen," he said.

Amid a background of rising cancer rates in many villages along the Huai and its tributaries, Huo began working on local factory leaders, persuading them to invest in better equipment to treat their waste water.

Huo recalled that as a child the river water next to his family home was red.

"We'd often find ducks and geese gone. When we'd look for them, they’d be found dead in the water," Huo said.

"I've always been one to get emotional about things. Why are there so many cases of cancer? As soon as evidence is sought, you find it in the water," he said.

Implementing the law

According to environmental experts, China has high standards for environmental protection, with rules and regulations specifically aimed at cleaning up the Huai River basin area in particular, and heavy fines for enterprises that won't comply.

But the problem, they say, lies with implementing the law.

Huo said Lotus Group, one of the main polluters of the river, was discharging 12,000 tons of raw effluent into the river each day, accounting for 60 percent of the total waste entering the river.

In 2003, SEPA fined Lotus 10,000,000 yuan, and ordered them to clean up their act. That year, Huo founded the Huai River Defenders, which recruited a network of low-profile but dedicated volunteers to keep an eye on the river's pollution levels.

"We told them to maintain [records of] public environmental information. In the production process, they should state how much water was used, how much water was polluted, and what the contamination levels are," Huo said.

"As it’s regulated, what levels are being achieved, how much is being discharged, and where is the waste being discharged exactly? We told them to make these matters public. They listened."

Changes made

In 2005, Lotus Group carried out a reorganization of leading personnel, dismissing former executives in charge of pollution, and working together with the company and environmental officials.

"We look at environmental protection as the lifeline of business. If the environment is polluted, enterprises won’t have a life," said Yan Erpeng, head of environmental protection at Lotus.

"[The enterprises] spend a lot of money. Since the water became regulated in 1996, it’s probably been about 300 million yuan," Yan said.

SEPA slapped further restrictions on polluters along the Huai river and tributaries in 2007, warning Lotus that it could still face closure unless it further improved its waste-water treatment standards.

According to Yan, the company also worked closely with Huo's Huai River Defenders.

"The Huai River Defenders played a supervisory role in water treatment, facilities, and operations, assessing whether drainage and on-site sampling was meeting standards," Yan said.

Now, according to Huo, Lotus waste-water treatment procedures exceed national standards for environmental protection.

"It was an advancement of our work. Pressure is what makes you improve," he added.

Cautious activism

Environmental activists say they have to be careful not to anger local officials, in spite of declarations that their supervision is "welcome."

Liuwan township government official Wang Feng, whose town lies within the Huai River network in Renqiu county, Hebei province, said at a recent news conference that Huo was welcome in his town, but local activists told a different story.

Liuwan resident and Huai River Defender Wu Yuerong said Huo was considered an unwanted visitor by most officials.

"They control him, and don't allow Huo Daishan to come. They say it'll tarnish our reputation here if he does," Wu said.

"They told me not to concern myself with it, and said it wouldn't be beneficial. And since then Huo Daishan rarely comes here," he said.

And in Henan's Shenqiu county, retired worker and environmental protection volunteer Wang Baocai said local officials were far from sympathetic to attempts to clean up local rivers.

"There's too much corruption now," Wang said. "If you go to them with something, they'll pick fights with you and say that you’ve come to embarrass them."

Authorities have also pulled the plug on the Huai River Defenders' Web site after it published an article criticizing the environmental record of local officials.

Original reporting in Mandarin by Shen Hua. Mandarin service director: Jennifer Chou. Written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.