China once had an internet archive run by researchers at Peking University that allowed users to perform keyword searches of more than 2.5 billion historical web pages from millions of websites in Chinese.

According to a snapshot of the site from 2005 stored by the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine, members of the public were invited to "browse the permanently saved historical web pages" and "browse through the websites of the past."

The site described itself as a "public service" that would help users to "understand how major historical events unfolded."

But the website failed to load when tested by RFA from Taiwan and Europe on Thursday.

The apparent unavailability of the archive comes amid growing concern among Chinese speakers both in China and overseas over rapidly diminishing access to online information in Chinese, particularly about the country's recent history.

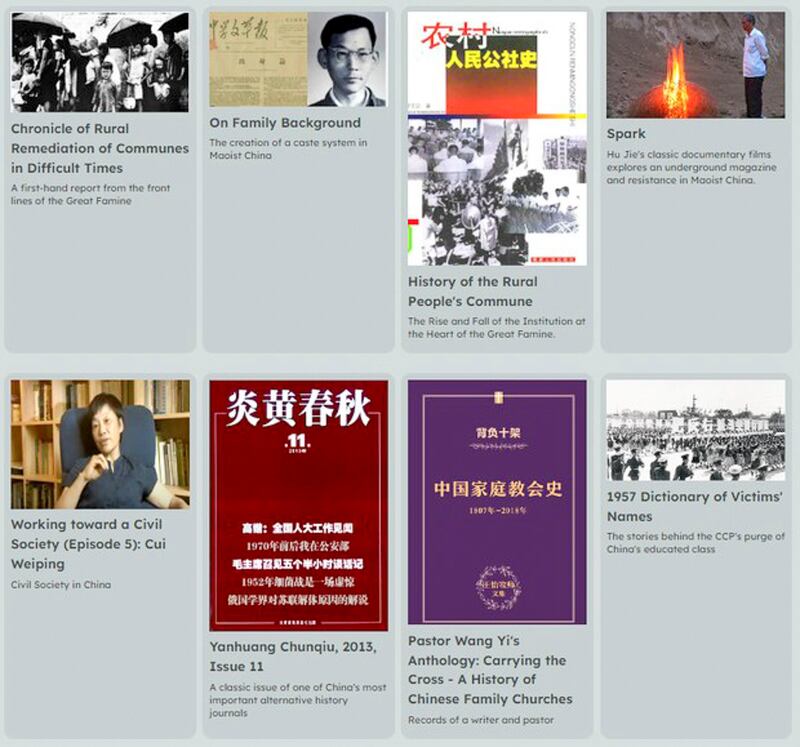

Volunteers at the U.S.-based China Unofficial Archive are battling to conserve material that has been censored under Xi and his predecessors.

Archived news articles about events from just a few years ago are no longer showing up on internet searches in China, cutting off access to the country's recent history from all but the most resourceful researchers, scholars told RFA Mandarin in recent interviews.

Fast disappearing

Politically charged events like the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen massacre have long been strictly censored from school and university textbooks, from public spaces and online.

But researchers say that less sensitive material is also fast disappearing, making it harder for people to form a picture of what people were doing, saying or thinking just a couple of decades ago, before President Xi Jinping took power.

Concerns about the unavailability of archived news stories and commentary were detailed in a recent blog post reposted on several Chinese platforms titled, "The collapse of the Chinese internet is accelerating," detailing an attempt to find news stories about Alibaba founder Jack Ma dating back to the turn of the century.

The article cited a Baidu search for stories about Ma dated from May 22, 1998, to May 22, 2005, which returned a grand total of one article from the early years of Alibaba's rise from e-commerce upstart to global technology conglomerate, and even that story was dated from 2021.

"In other words, if we want to understand Jack Ma's experiences, reports, people's discussions about him, his speeches, the company's development history, etc. during that period, the amount of effective original information we can get is zero," author He Jiayan wrote.

"After the rise of mobile Internet, Chinese content on the traditional internet has all but disappeared," He wrote, adding that Chinese-language search results via Google and Bing also yielded scanty results.

"My rough estimate is that more than 99% has disappeared," the author wrote, adding that results were similar for other high-ranking business people and celebrities from the pre-mobile era.

"Almost everything you see and create now, together with this article and this platform, will eventually be submerged in the void," the article warned, citing the disappearance of archived content from websites that were popular at the time, like NetEase, the Sina blogging platform, Baidu Tieba and the Tianya forum among many others.

"We once thought the internet would remember stuff -- we never expected its memory would be akin to that of a goldfish," He wrote.

Tightening grip

Part of the reason archived content is quickly disappearing in China is the tightening of government censorship in recent years, said a scholar based in the southwestern city of Chongqing who gave only the surname Wang for fear of reprisals.

"Articles from more than 10 years ago are likely to get someone into trouble today," Wang said. "A lot of Chinese media act under the leadership of the [ruling Chinese Communist] Party, so it's inevitable that they will delete stuff."

Some of it has been deleted on strict government orders, according to a retired university lecturer from the southwestern province of Guizhou who gave only the surname Zhang for fear of reprisals.

“The State Education Commission issued a notice to the whole country, which basically meant that no critical articles could appear on the internet,” Zhang said. “University campuses were regarded as an important battlefield that had to promote the main theme [of government propaganda].”

“It said that university online forums weren’t outside the law, so all posts should be deleted, and all comment functions shut down,” she said.

Lu Jun, co-founder of the non-government Beijing Yirenping Center, which campaigned for human rights in healthcare, said he had noticed content disappearing too.

"I discovered a while back that there's no trace any more of the anti-discrimination... actions we took in our early years that were reported by mainstream and even state media in China, and reposted on a large number of official websites at the time," Lu said.

Lu, who now lives overseas, said that while internet content disappears everywhere in the world, the problem is particularly acute in China "because the Chinese Communist Party plays an important role in controlling the flow of information and in online censorship."

According to He Jiayan's article, "it seems that there is a monster that devours web pages ... first in small bites, then in large gulps."

Days of relative freedom

Tseng Chien-yuen, an associate professor at Taiwan's Central University, said web content also disappears in Taiwan, too, but mostly based on commercial considerations.

"There was an era of relative freedom and diversity in China," Tseng said, referring to the period before Xi Jinping took power.

"For example, I used to regularly browse the Century China website during the Hu Jintao era, and often made posts there," he said. "Now there's no trace of it left at all -- a lot of people don't even know that such a website existed in China."

Century China shut down in 2007 after receiving an order from "the relevant authorities," according to the overseas-based China Digital Times.

Feng Chongyi, associate professor of Chinese studies at the University of Technology Sydney, said the disappearance of such websites and archived news materials will have a huge impact on Chinese people's access to their own recent history.

"It's pretty horrifying, but I think it has its roots in the political system," Feng said, citing a slew of recent national security legislation that make publishers far more wary of what information is still visible online.

"Politically speaking, the past was once grayed out, but now it's been blacked out entirely."

Translated with additional reporting by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.