By rights, jailed Hong Kong rights lawyer Chow Hang-tung ought to have gotten a love letter from her Guangzhou-based fiance and fellow rights activist Ye Du, on Lantern Festival.

But it was unclear if his message of lifelong love and support -- published in a major newspaper -- survived recent censorship of their correspondence by prison guards.

Ye's letter to Chow, an award-winning activist who has been behind bars since September 2021 for organizing vigils marking the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, expresses his sadness that the couple seem fated to be permanently apart.

"We're so far apart, yet you are always in my thoughts," wrote Ye, who proposed to Chow in July 2021 via a letter printed in the Ming Pao newspaper, but who is himself under a travel ban imposed by the authorities, to mark the 15th day of the first lunar month, a festival equivalent to Valentine's Day in the Chinese calendar.

"I will keep fighting for freedom and for our love for the rest of my life," the letter, which laments that the couple have never spent Lantern Festival together, reads.

Ye said that whenever he speaks out on behalf of Chow, he is typically hauled in by state security police for questioning soon afterwards.

"But this heavy pressure from the powers that be has never destroyed the love between us," he wrote.

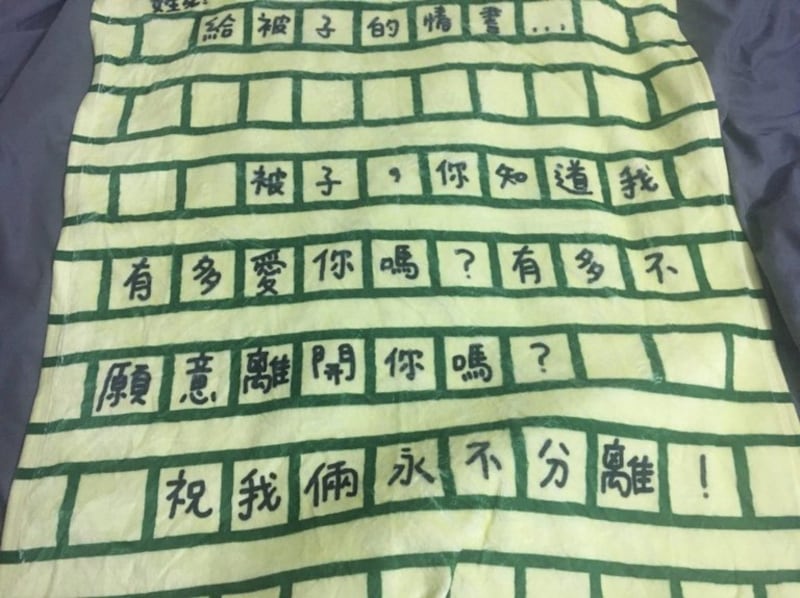

His letter also recalls gifts the couple have previously exchanged on Lantern Festival – a large Kindle for Chow to read more comfortably in prison, and a quilt for Ye emblazoned with the message: "May we never be apart!"

Delivering a message

It is unclear whether Chow has read the letter yet. Reports emerged last week that Correctional Services guards at her prison had ripped out the pages from the copies of the Ming Pao delivered to the prison, the InMediaHK news website reported on Feb. 15.

It quoted correctional officials as saying that the content had been judged a threat either to prisoner rehabilitation or to prison order.

Ye wrote on his Facebook page on Jan. 27 that his letter "was there for the whole world to read -- except her."

He called on anyone visiting Chow to take a copy to the prison with them.

The couple's correspondence has even been denounced in the ruling Chinese Communist Party-backed media.

Hong Kong's Ta Kung Pao published an op-ed article last week accusing the reporting around their love letters as "cheap sensationalism," and "manipulating people's emotions with propaganda."

Pro-China lawmaker Maxine Yao also hit out Ye's letter in the government-backed Bauhinia magazine, calling it "indecent," "explicit," and accusing it of "political manipulation" as Chow's case continues to progress through the courts.

"The logic of the 'love letter' doesn't make sense. It forcefully confuses the original author's love experience with anti-Chinese thoughts," Yao wrote.

The Ta Kung Pao described it as "soft propaganda" on the part of overseas anti-China forces seeking to destabilize Hong Kong.

In-prison censorship

Several people familiar with prison life in Hong Kong said it is fairly common for Correctional Services prison guards to censor newspapers delivered to its prison, and the practice is often used to target individual inmates.

Prison rules allow guards to have the last say over prisoners' reading material, and to ban anything deemed sensitive, including instructions on how to escape, or anything seen as an incitement to commit further crimes.

In practice, political topics like the trial of prominent prisoners including Jimmy Lai, are increasingly being censored, as is any material relating to the 2019 protest movement or the 2014 Umbrella Movement, said people familiar with prison life in Hong Kong, amid an ongoing crackdown on dissent and political opposition.

The Correctional Service Department replied to a detailed list of questions from RFA Cantonese about the censorship of prisoners' reading materials with a single sentence: "The article you mentioned was distributed to prisoners/the prisoner," but without specifying which article the reply referred to.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie .