In the midst of the intricate geopolitical chessboard, the death of former Chinese premier Li Keqiang at 68 marks the end of an era for a diplomat internationally recognized for his dedication to global relations. Li’s tenure was a unique juxtaposition: sandwiched between the autocratic leadership of Xi Jinping and escalating global challenges, notably the U.S.-China trade war.

Li’s involvement in numerous international summits showcased his intent in strengthening global alliances and addressing multifaceted challenges. China, under his aegis, witnessed pivotal moments: from economic reforms to public health crises and environmental issues. He was a stalwart believer in innovation, technological progression and sustainable development.

When Li took the reins of the State Council in 2012, he focused on economic reform, poverty eradication and championed a more consumer-driven economic model. His significant influence facilitated comprehensive economic reforms and opened China’s markets to foreign investment. He was President Hu Jintao’s likely successor, but fate had other plans when Xi Jinping took the helm of the Communist Party in 2012.

As Gerry Groot, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at the University of Adelaide, said, Li’s role in driving the Party’s policy might be overstated, but many experts saw in Li the promise of a moderate technocrat.

“There would have been many differences between the way China was run compared to under Xi,” said Groot. “But I am one who believes that the imperatives of the system drive much of the general direction of Party policy and overall the role of individuals is overstated.”

Li's economic diplomacy stood out. He made efforts to stabilize relations with trading behemoths like the U.S. and the European Union while promoting cooperation.

Ian Chong, a political scientist at the National University of Singapore, acknowledged Li’s groundwork, but observed that his influence in major policy decisions seemed minimal compared to his predecessors.

“Li's legacy is one of an economic reformer and technocrat, but one who was subordinate to Xi,” said Chong.

“He’s associated with fixing problems and being on the ground, especially in the wake of crises or disasters. However, he appeared to have less of a role in the shaping of major policy directions, as compared to his predecessors, Wen Jiabao and Zhu Rongji,” he added.

Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the London University School of Oriental and African Studies, speaking when Li was stepping down as premier in March this year, was kinder in his view of Li.

“Li was sidelined by Xi deliberately and in an openly humiliating way … He did not really have a chance to make much of an impact.”

Under Xi’s leadership, China has increasingly veered towards autocracy, and the economic downturn after the COVID-19 pandemic further complicated matters. It’s no surprise then that Li’s demise might stir reactions among the Chinese populace, potentially perceived as protests by Beijing.

Public mourning

On Chinese social media platforms on Friday, a deluge of posts remembering Li’s reformist efforts could be seen. A reel of Li speaking about the difficulties that farmers face was reposted extensively.

“My tears didn’t stop flowing at the end of his speech,” said one netizen.

Li’s passing is unlikely to incite the extensive and spontaneous outpouring of public grief seen when another former premier Zhou Enlai died in January 1976. Zhou died when China was in the midst of political turmoil caused by “Great Helmsman” Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

Zhou was widely seen at the time as a moderating and stabilizing force, admired for his pragmatism, diplomatic skills and efforts to mitigate some of the more extreme policies of the political upheaval.

The government then initially tried to put down the public mourning, but it couldn’t be entirely suppressed.

It’s likely that Li Keqiang will be remembered for being committed to economic reform, innovation and diplomacy even if, as Adelaide sinologist Groot points out, it’s the party that rules at the end of the day, not individuals.

Quest for blue sky

Born on July 1, 1955, in Hefei, Anhui province, Li Keqiang rose through the ranks of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to become one of its most influential figures.

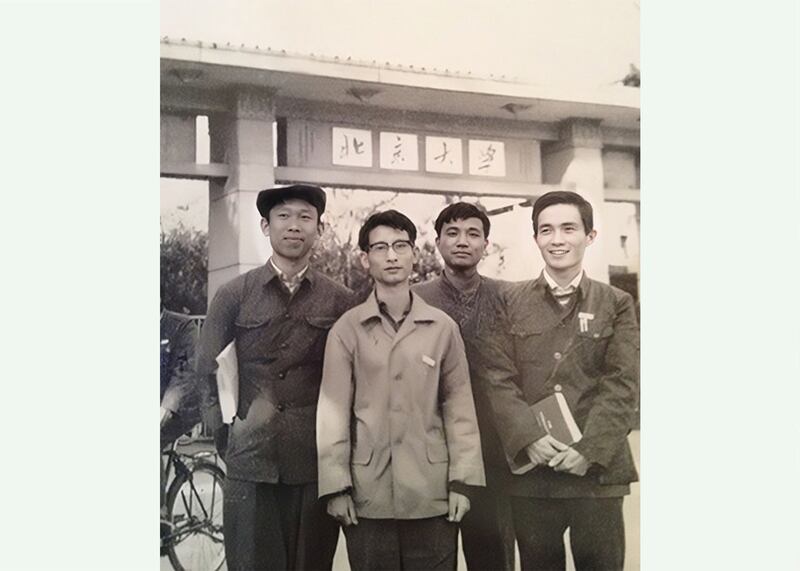

He earned a degree in law in 1977 at Peking University and his academic excellence quickly caught the attention of Party leaders at a time when commitment to economic transformation was considered important.

Upon assuming the role of premier in 2012, he confronted the challenges of an economic model heavily reliant on exports and investment, pushing for a shift towards a more consumption-driven economy. His efforts laid the groundwork for China’s historically unprecedented economic growth and its astounding rise in global influence.

With Li’s passing, the political and social landscape of China remains uncertain, but discussions are inevitable. His straightforward communication with the people, in contrast to Xi’s more intricate discourse, will stand out among the many facets of his leadership that will be remembered.

In one of Li’s more memorable moments, during a press conference in 2013 as premier, he was asked about Chinese people’s concern over severe smog and environmental issues.

In response, Li candidly stated that he had checked the air quality data in Beijing and said the Chinese government should be more transparent about the situation, saying, “I hope we can … work hard to make the sky blue again.”

Li’s “blue again” comment resonated and became a symbol of Li’s commitment to addressing China’s environmental and other challenges and became a rallying cry for environmental activists and citizens.

As China tried to get back to normal in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, Australian National University political scientist Wen-Ti Sung pointed out that Li said publicly, “600 million Chinese people still make barely 1,000 RMB (US$137) a month. After COVID, people’s livelihood should be our priority.’’

"Li Keqiang will probably be remembered for this line – the former premier who looked out for the little guys," said Sung on X, formerly known as Twitter on Friday.

Xi Jinping has had no such inspirational touches upon the people he rules, and it is unlikely this will be unnoticed in the days ahead.

Edited by Taejun Kang and Mike Firn