As most Chinese nationals at the opening of the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris waved Chinese national flags in a bid to cheer their team on, some were there holding banners that carried a very different message -- protesting Beijing's human rights record.

As French police cordoned off major roads outside key venues on Friday evening ahead of the opening ceremony along the River Seine, Liu Feilong and Qian Yun joined the eager crowd.

But instead of cheering, they held up a placard in support of the democratic island of Taiwan, which is targeted by Chinese military incursions on a near-daily basis.

The slogan on the placard was partly aimed at Liu Shaye, China's outspoken ambassador to France who recently described Taiwan's democratically elected government as "a rebel regime" that could be toppled by China at any time.

"Liu Shaye and the Chinese Communist Party are the real rebel regime," the placard said.

The Chinese government's propaganda machine has kicked into high gear to ensure favorable coverage at this year's Olympics, with Chinese athletes ordered not to talk to journalists not sanctioned by senior officials.

But there is one group of Chinese nationals who sometimes slip through the cracks -- activists and dissidents in exile.

Liu and Qian's protest went largely unnoticed amid the throngs of sports fans on the Parisian streets on the opening night of the Games.

Fleeing persecution in China

But for some activists in exile, who also protested during a visit to Paris by Chinese President Xi Jinping in May, such actions are becoming a way of life.

Two hours earlier, Liu and Qian turned up outside the Chinese embassy in Paris and held up a Chinese national flag, not out of patriotic support for Chinese athletes, but in protest over human rights issues.

On their version of the flag, the group of five gold stars had a black skull scrawled on it.

"I just want to express my hope that the Chinese government will care about human rights," Qian told RFA Mandarin.

Neither Liu nor Qian is a stranger to political persecution in China.

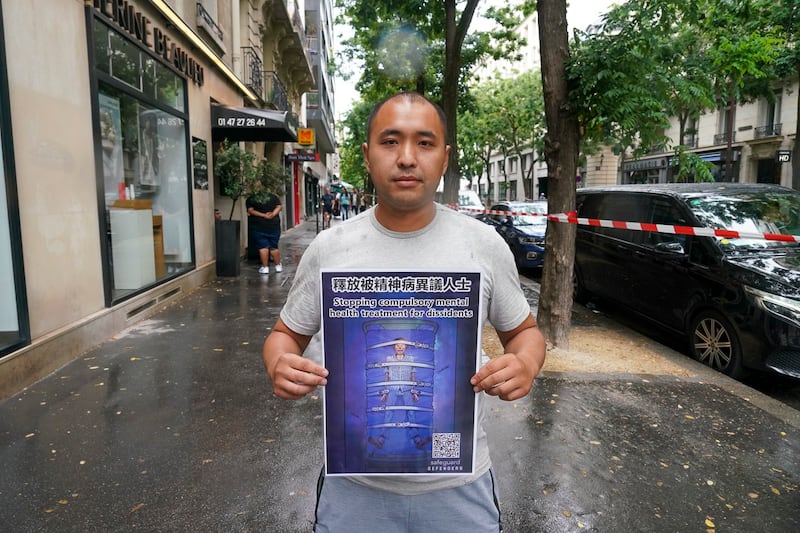

Qian, who fled China in 2021 and is now in his early thirties, was kicked out of junior high school for expressing doubts about the official view of history. He and his family were harassed and targeted by police and local government officials, who labeled him "mentally ill" in 2014, putting him at risk of detention at any time.

He called on the Chinese government to "stop engaging in this kind of persecution."

"The way they labeled me as mentally ill was too casual," said Qian, who cited the 2018 case of Dong Yaoqiong, forcibly detained in a psychiatric facility in the central province of Hunan after she splashed black ink over a poster of Xi Jinping for a social media video protest.

RELATED STORIES

[ Chinese social media users slam athletes over failure to deliver goldOpens in new window ]

[ China's Olympic team denies issues with summer heat in ParisOpens in new window ]

‘Long-arm’ law enforcement

Liu, who hails from the southern province of Guangdong and wore a black T-shirt emblazoned with the words "Guangdong Youth" in Chinese and English, said he also left China in 2021, in the hope of living in greater freedom in the Netherlands.

"Freedom that different voices and different political views are expressed, free from fear, and without having to worry about being held accountable or investigated," he said.

But even in a free country, some risks remain, with overseas dissidents and activists frequently reporting surveillance and harassment by supporters and agents of the Chinese state, even on foreign soil.

In May, a close associate of Liu's had first-hand experience of Beijing's "long-arm" law enforcement methods.

"[Fellow activist] Chen Kui and I protested against Xi Jinping's visit to Paris," he said. "The next day, state security police in China paid a visit to his friends and relatives and threatened them."

Similar treatment was meted out to another overseas activist known by his nickname Jiang Bu, said Liu, adding that he himself has cut off all contact with his folks back home in a bid to protect them.

"The Chinese government really fears this sort of opposition voice," he said.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie.