Updated on Sept. 21, 2023, at 11:25 a.m. ET

Only yesterday, or so it seems, the world beat its way to China’s door and returned with breathless tales of high-speed trains and giddying architectural triumphs.

China was the economic juggernaut that dazzled all – and it jumpstarted the global economy in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Today, says Kevin Carrico, senior lecturer in Chinese studies at Monash University, it’s become a “pariah state.”

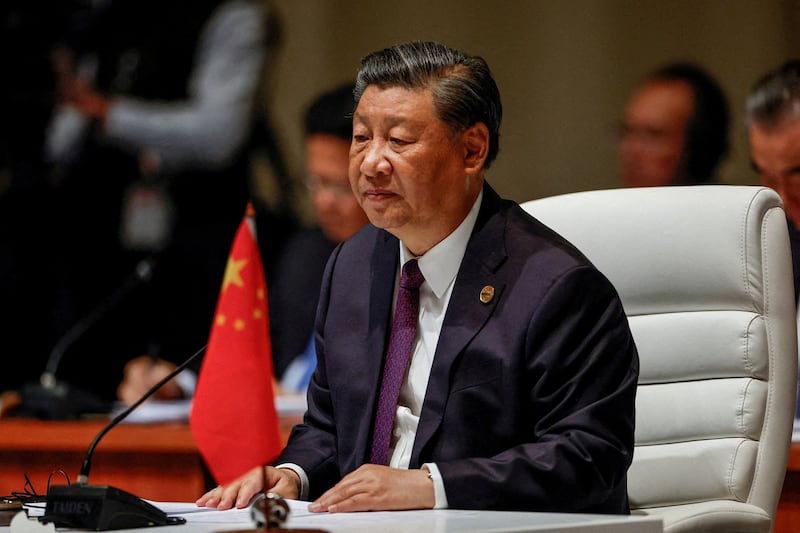

Nearly one year into his third term, President Xi Jinping presides over a China that has turned away from the opening-and-reform buzz of the Deng Xiaoping years. Indeed, it has become an emergent global power that even appears to be turning its back on the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) one undeniably great achievement – economic growth that Beijing alleges lifted 800 million out of poverty.

In recent years, entrepreneurs have been bundled away, foreign businesses targeted amid the passing of new counter-espionage laws, the property sector faces collapse amid tepid demand and weak consumer confidence and capital and loans are reportedly being channeled away from the private sector into State Owned Enterprises.

China's local governments are reportedly so in debt they're cutting employee incomes and imposing arbitrary fines on citizens to raise money as Xi balks against bailouts as a form of "welfarism," which he argues leads to laziness.

For critics, the easy target of blame is the party chief himself – after all, he’s awarded himself such mind-boggling, wide-ranging power, why even look for another target of blame?

But some China watchers suggest that Xi, a Maoist of limited education, has inherited forces borne of long-ago established party policies that now threaten the party, pressuring him to reflexively respond with an iron fist.

While few if any China-watchers think he's doing a good job, some scholars such as Carnegie Endowment economist Michael Pettis argue he's the victim of structural problems that date back to at least 2007.

“While China's growth is largely built on private enterprises, the Communist Party is a Leninist organization which doesn't tolerate any power not of its own,” says Australian-based political analyst and former Chinese diplomat Han Yang.

“The private enterprises have grown so big to the point that their aspirations will be a source of challenge to the leadership of the Party, and Xi can't allow that.”

In Pettis's view, Xi has inherited a highly indebted structural mess that perhaps could have been corrected in 2007 under Hu Jintao, but Xi is dealing with "rising imbalances and unsustainable increases in debt, both of which were the very consequences of the excessively high growth rates of the past 10-15 years."

In the face of problems that may represent an existential threat to the CCP, Xi, observers agree, will make decisions that to outsiders seem bad, but are to his mind survival reflexes.

‘Poorly educated, unimaginative’

“Xi seems to be dedicated to making the worst decisions possible in almost every scenario,” says Carrico. “Xinjiang, COVID, relations with the world. He has turned a rising power that was being integrated into the world system into a pariah state. He is the wrong man for the moment, but also the epitome of the flaws of the CCP system.”

Noted American Chinese scholar Perry Link agrees.

“My view is that Xi is out of his depth,” Link said in an email. “He’s very good at the infighting and backstabbing that one needs in order to rise in the CCP system. But once on top, he did not know what to do.”

Link describes Xi as “unimaginative” and “poorly educated (only through junior high – his post-secondary degrees are on-paper only),” asking, “Where could he turn for a model? Only to the Mao system, which he did know – sort of.”

Says Australian-based Yang, “Xi’s ideology differs from the previous three leaders [Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao] in the way he put his personality cult at the center of … governance, jettisoning the ‘collective leadership’ model established by Deng after learning the lessons of Mao era.”

But despite a number of recent high-level disappearances of Xi appointees – notably a foreign minister, Qin Gang, and most recently Minister of Defense Li Shangfu – nobody that RFA spoke to thought that Xi is threatened in the short term.

“The disappearance of Qin Gang and Li Shangfhu – both hand-picked and fast tracked by Xi months ago – the removal of the PLA’s two commanders of elite Army Rocket force, the failure of the Xi to attend a G20 for the first time and the release of a wordy Ministry of Foreign Affairs statement on global governance – all while the economy is unstable – makes for a lot of speculation,” said George Magnus, research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre and author of “Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy.”

But, added Magnus, “I don’t see an imminent threat to Xi.”

Australian-based Yang agreed, noting that Xi will prioritize CCP security and continued unchallenged CCP rule over the economy.

“Either the Party relaxes its control of the economy and … society to allow further growth, or Xi reasserts the Party’s absolute leadership over everything to maintain power,” said Yang.

“My bet is on the latter.”

‘Inflection points’

“Peak Xi?” asks Jeremy Goldkorn, editor in chief of the China Project, “It depends what you mean by peak.”

Goldkorn suggests that Xi’s peak moment was probably “when he took over as Party General Secretary and Central Military Commission Chairman from Hu Jintao, or perhaps January 5, 2013, when the New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof predicted that Xi would ‘spearhead a resurgence of economic reform, and probably some political easing as well.’”

Kristoff, Goldkorn added, had also predicted that “Mao’s body will be hauled out of Tiananmen Square … and Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning writer, will be released from prison.

Liu Xiaobo died in prison despite being awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. Mao still rests in his mausoleum in Tiananmen Square.

“Although many people inside and outside China continued to nurture hopes and dreams about Xi for years after that – indeed, some still do – I personally began to despair of the direction the country was taking after the leak of Document Number Nine in the summer of 2013,” said Goldkorn.

“That document was circulated amongst senior Party officials in 2012, and it set out in explicit terms that Xi Jinping wanted to reverse the direction of China's political and intellectual opening to the world. So perhaps the summer of 2013 could also qualify as an inflection point.”

Goldkorn says further inflection points include February 2018 when the Central Committee proposed removing the two term limit on “president” and November 2020, when Ant Group’s IPO was suspended and Jack Ma was sent into early retirement.

The concern is further “inflection points.”

Riding the tiger

Xi, according to China scholar Link, is so preoccupied with maintaining his dominant role that the textual reams of “Xi Jinping thought” foisted on the people by state publishing houses is nothing more than “window dressing.”

“His only major deviation from the Mao model has been to claim himself avatar of the great 5,000 years of Chinese civilization. But both of these – the Mao model and great-civilization claim – are but window-dressing.”

Says Carrico of Monash, “Xi does not seem to have any solution other than centralizing control and having people read his mind-numbing ‘thought.’ These are not solutions, but rather the source of the problems, reproduced as solutions.”

“His real preoccupation is with staying on top within the untrusting and strife-ridden CCP,” commented Link. “That struggle happens inside a black box, of course, so it is hard for us on the outside to make informed predictions. But my sense is that he is not nearly as secure as his surface bravado claims.”

Wu’er Kaixi, a student leader on Tiananmen Square in 1989 and in exile since, said, “Xi Jinping took China from a one-party dictatorship to a one-man dictatorship and there are probably 200 powerful families in China who aren’t happy about that – countless elite party interest groups and private entrepreneurs that aren’t happy about that.”

Oxford’s Magnus, who sees “no imminent threat to Xi,” added, “His longevity in a 10 year term? Maybe now open to some doubt.”

Edited by Mike Firn and Elaine Chan.

This story has been updated with additional attribution and minor edits.