French photographer Catherine Henriette had just completed a master’s degree in Asian languages when she decided to visit China.

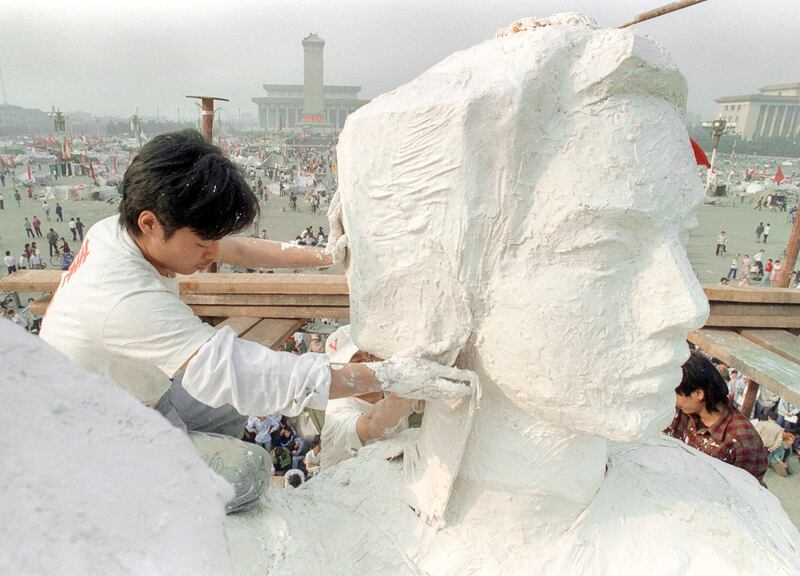

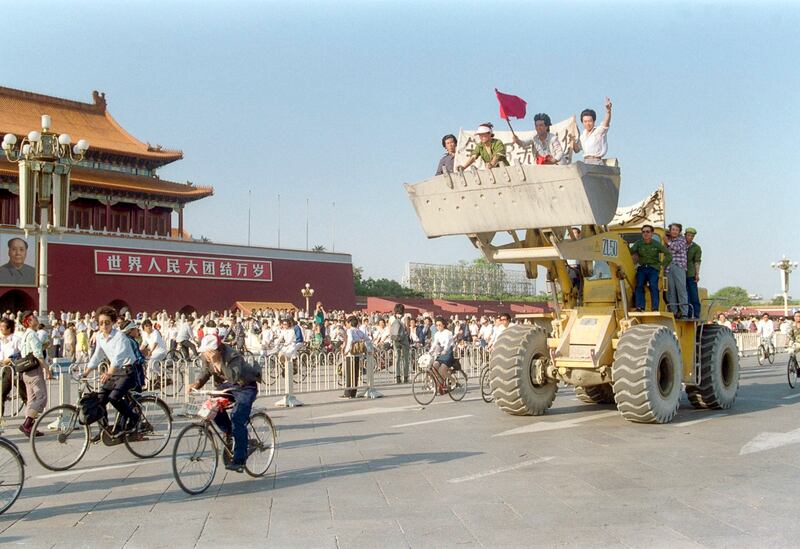

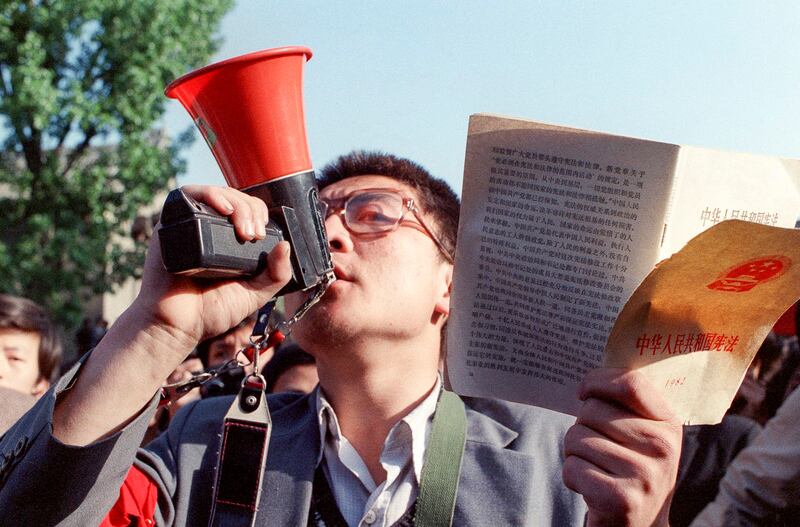

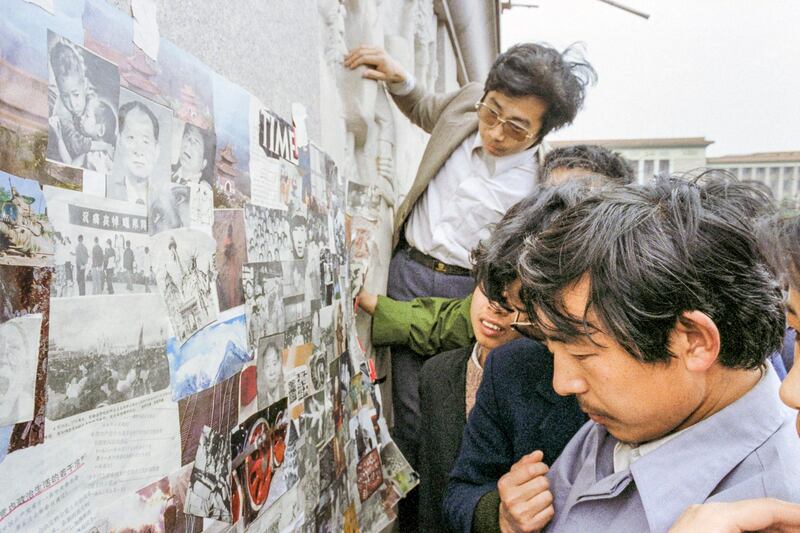

She was hired by Agence France-Presse in April 1989 and almost immediately began photographing the largest pro-democracy demonstrations in China’s history. One month later, the Tiananmen Square crackdown began as the 29-year-old was still learning the new role.

In an interview with Radio Free Asia’s Eric Kayne originally in French and translated to English, Henriette recalls the experience of covering the student demonstrations.

RFA: What drew you to Tiananmen Square during the student democracy demonstrations in 1989? What was your initial impression of the atmosphere and the people involved?

Henriette: I was a photographer for Agence France-Presse at the time, so it was just my job that brought me to Tiananmen Square. My first impression was disbelief at what was happening before my eyes.

RFA: Can you describe your experience of photographing the events at Tiananmen Square? What challenges did you face as a photographer during such tumultuous times?

Henriette: It was a very joyful and very exhilarating moment. I was a beginner photographer so I had to learn quickly because the movement just kept growing and growing every day. The challenge was a physical challenge. I had to hold on, because I was the only one taking photos for AFP. I was exhausted because it never stopped.

RFA: Were there any particular moments or scenes that left a lasting impact on you? Could you share the story behind one of your most memorable photographs from that time?

Henriette: Every day was different. Perhaps the most incredible moment was when Zhao Ziyang came out of the Great Hall of the People to visit the students and try to talk with them. In a country like China, it was surreal.

RFA: How do you believe your photographs from Tiananmen Square contributed to the broader narrative of the democracy demonstrations? Do you feel they helped to amplify the voices of the protesters?

Henriette: At the time, my photos were widely used in magazines and newspapers. So yes, I think that without knowing it, I contributed to making the movement known.

RFA: Looking back, how do you feel about the role of photography in shaping historical memory, especially regarding events like the Tiananmen Square protests?

Henriette: Honestly, my only experience was with the events in Tiananmen Square. I was only 29 years old and I was just starting out in photography. I took my job at AFP in April 1989. I didn't have enough experience in press photography to say whether it has the power to influence the course of history. But look at the photo of the man in front of the tanks (which I did not take) – it's an image forever anchored in our minds. Therefore, yes, I think that photography can mark collective memory in its own way.

RFA: In what ways do you think the events you witnessed and captured at Tiananmen Square have influenced your approach to photography and storytelling throughout your career?

Henriette: It probably did influence my approach without me knowing it, but as I said, I was just starting my career as a photographer. I only did a few years of photojournalism, and of course being a photojournalist in China was a wonderful school for me. But since then I have evolved. I moved on to magazine photography and then to the more artistic photography that I still practice today.

RFA: Given the censorship and suppression of information surrounding the Tiananmen Square massacre, do you think it’s important for photographers and journalists to continue documenting and shedding light on such events?

Henriette: Of course, otherwise these events would be erased from history. In Chinese history books, there is no mention of Tiananmen.

RFA: Reflecting on your experiences at Tiananmen Square, what message or lessons would you like to convey to future generations about the power of photography in bearing witness to history?

Henriette: I would like to tell them not to take too many unnecessary risks. The "Tank Man" photo, which traveled all over the world, was taken from the balcony of the Beijing Hotel the day after the crackdown in the square. Every photo you take must carry a message. You have to find it. I think that a good photographer is the one who will think about that.

Translated by Claire McCrea.