Industrial overcapacity in China is the result of a number of political pressures and structural changes in the country's post-lockdown economy, and is unlikely to change any time soon, economists told RFA Mandarin in recent interviews.

U.S. officials have recently accused the Chinese government of over subsidizing certain industries, leading to overcapacity and a tendency to flood global markets with cheap products.

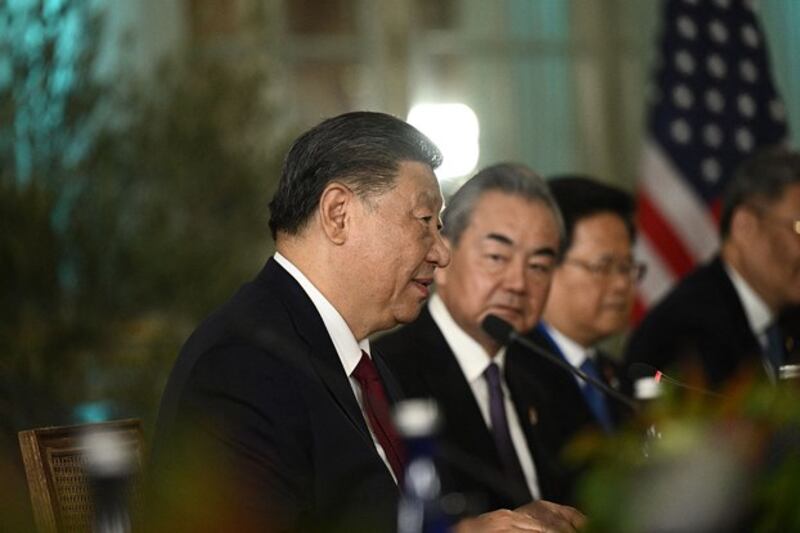

The issue, which Beijing says is a ploy by Washington to suppress it as a global competitor, was a key topic on the agenda during recent visits to Beijing by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who criticized China's "unfair" trade practices and the potential consequences of industrial overcapacity to global and U.S. markets, citing electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels in particular.

Foreign Minister Wang Yi retorted that "China's legitimate right to development is being unreasonably suppressed," calling on Washington to "stop hyping up the false narrative of China's overcapacity, lift illegal sanctions on Chinese companies and stop Adding Section 301 tariffs that violate WTO [World Trade Organization] rules," state media reported on April 30.

'Blind expansion'

So what does overcapacity in China look like? And how can it be addressed?

The top 20 automakers in China have a combined production capacity of some 35 million cars, but are currently only operating at less than 50% of capacity, according to a recent report from the Jiangsu Intelligent Connected Vehicle Innovation Center.

Many have benefited from government subsidies under a 10-year green energy development policy set and subsidized by Beijing, analysts told RFA Mandarin.

The report blamed "blind expansion" of capacity and "miscalculating development trends in the clean energy sector," adding that the mistake has cost Chinese automakers dear. Figures from China's National Bureau of Statistics show that the auto industry only garnered profits of 5% for the whole of 2023, for example.

Part of the issue is that, structurally, the Chinese economy is geared up to fill export orders, with more than 2% of its GDP reliant on exports, according to a former U.S. trade official.

Another issue is the tendency of the ruling Chinese Communist Party to order certain industries to ramp up production — in this case, green energy — to meet long-term political goals, namely, the 10-year "Made in China" action plan, which launched in 2015, former U.S. Department of Commerce official Patrick Mulloy told RFA Mandarin.

Such plans inevitably involve huge amounts of government subsidies for targeted industries, evidence of which Mulloy said he had seen personally on official visits to China while serving on the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

“The fundamental problem is that we have a complete imbalance in our economic relationship with China,” Mulloy told RFA Mandarin in a recent interview.

“I think the Chinese leadership has decided no, we want to be dominant in these new industries … electric vehicles, batteries, solar, all of these sorts of things. And they have decided that they're going to pump their money in, to subsidize these industries and exporting them.”

'The deformed monster'

Meanwhile, U.S. officials have little recourse to the WTO, because Beijing doesn't supply all of the data they would need to make a case through that body, hence the harder line now being taken in public by U.S. officials on the issue, Mulloy said.

"The most fundamental reason for overcapacity in China is top-down, autocratic control exercised by the Chinese Communist Party," Xie Tian, a professor at the University of South Carolina's Aiken School of Business. "Or rather, it's the deformed monster produced by the fusion of a market economy with that autocratic system."

Taking electric vehicles as an example, Xie said China currently has more than 200 electric vehicle factories, with an overall production capacity that exceeds domestic demand.

Over-investment leads to diminishing returns, forcing companies to engage in life-or-death price wars just to survive, Xie said, adding that many of those companies would never have gotten started in the first place in a market economy.

"The central government comes up with a policy, and subsidies, and everyone wants a slice of the pie," Xie said. "So they rush to production without worrying whether or not these products will sell."

"They don't care about that, because this is a way for local government officials to show off their political achievements," he said, adding that the promotion prospects of local officials is heavily influenced by local GDP figures during their tenure, and new factories inflate those number for long enough for the official to be promoted elsewhere.

Yet much of this "growth" is illusory, and there is scant political will to allow any of these subsidized companies to go bankrupt, which is what should happen in a market economy, Xie said.

"That would mean a self-created wave of unemployment and bankruptcies," he said, adding that the government may eventually be forced to allow this to happen.

'Overcapacity if back'

Excess industrial capacity is nothing new in China, according to a March 26 report from the U.S.-based Rhodium Group.

"China has a long history of structural overcapacity," the report said, adding that the last severe episode happened in 2014-2016, a few years after the government launched a massive stimulus package in response to the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

"After years of retreat, anecdotal evidence is mounting that overcapacity is back in China," the report said, citing clean technology in particular.

Capacity utilization rates for silicon wafers fell to 57% in 2022 from 78% in 2019, the report said, while adding that production of lithium-ion batteries was 1.9 times the volume of domestically installed batteries in 2022 and that similar problems are also now being seen in the industrial sector as a whole.

The report said inventory levels -- the amount of goods that have yet to exit the factory gates -- are also sky-high.

U.S.-based economist Cheng Xiaonong agreed.

"There is no industry in China that doesn't have overcapacity," Cheng said. "The problem is that the production capacity structure in China has been based from the start on the concept of China as the 'workshop of the world.'"

"The problem is that this dream is now shattered," he said.

Cheng said he doesn't believe that ongoing tensions with the international community are actually caused by this issue, however. He believes foreign governments are using trade as a way to contain and curb a newly aggressive China, which they see as a threat to global peace and stability. Blinken, for example, took issue with China's export of materials to Russia that could aid its war effort in Ukraine.

"The trade war isn't caused by overcapacity; rather, there is a trade war because China threatens the peace and security of every country," Cheng said. "The trade war is a means for other countries to sanction China."

Antidote to overcapacity

Economists in China and overseas believe that the antidote to overcapacity in China is to stimulate domestic demand. But is this even possible?

Cheng doesn't think so, citing recent figures that show that, in 2021, more than 42% of the population was getting by on less than 1,090 yuan, or US$150, a month, while another 41% makes somewhere between that figure and 3,000 yuan, or US$415, a month.

"When 84% of the population has a per capita income of less than 3,000 [yuan] a month, it's not easy to stimulate consumption," he said. "Meanwhile, the Chinese government isn't using the money it has to improve people's lives — it's investing in military expansion and preparation for war."

U.S.-based current affairs commentator Zheng Xuguang believes that the Xi Jinping administration will be forced back into the old economic model, importing raw materials in huge quantities from overseas, and exporting the finished products.

"This coastal development strategy has driven growth in the central and western regions, in a pattern that still hasn't changed to this day," he said.

And that means China is likely to keep on trying to export all of those excess goods for the time being, according to Xie Tian.

"The Chinese Communist Party doesn't want unemployment to rise, so it doesn't want to reduce production capacity," he said. "When the domestic Chinese market can't absorb [the excess goods], it is forced to export them and to subsidize it further."

"That means manufacturers in other countries can't compete."

Additional reporting by Jenny Tang. Translated by Luisetta Mudie . Edited by Roseanne Gerin.