A well-known oil man who has been linked to numerous bribery schemes and sanctioned by the U.S. government struck deals in Angola while secretly working for China’s ruling party, his longtime business partner told a Hong Kong court.

The testimony, first reported today by Radio Free Asia, disputes decades of denials by Chinese officials that notorious fixer Sam Pa was seeking oil concessions in the country at Beijing’s behest.

Pa was arrested during a Chinese corruption investigation in 2015 and has not been heard from since. His former associate Lo Fonghung is suing Pa’s wife, Veronica Fung, for control of the business empire she built with him. Pa had never been listed as a shareholder of the companies he and Lo ran together, with Fung standing as a proxy in his place. With Pa having been incommunicado for close to nine years, Lo is challenging Fung’s standing to vote on corporate matters in his absence. The case commenced in 2020 and is ongoing.

Under cross-examination during a civil court hearing last November, Lo detailed how the Chinese government used several of their companies as a front to enter Angola, according to court transcripts obtained by RFA.

Lo and Pa’s first joint venture was a highly successful bid to break into the Angolan oil market in the early 2000s as the African state emerged from a bloody 27-year civil war. They did so on the confidential instructions of the Chinese Communist Party, Lo said.

“I was directly working for the Central Committee of the party,” she told the court.

“When we went to obtain the oil resources, it was an action to break the existing strategic pattern of the United States and Western countries in Africa and Angola, so we had to keep it a secret.”

Her mission with Pa in Angola had to be disguised as a private commercial venture, Lo said, or else it might draw objections from China’s strategic rivals. The approach, she said, resulted in a successful mission.

“At that time, at first, China could only get 10,000 barrels [of oil] a day from Angola. Through our efforts we could get 400,000 barrels a day,” Lo testified.

Today, the vast majority of Angola’s oil goes to China.

While Beijing has long denied that Pa and his companies enjoyed any kind of relationship with the Chinese government, Lo’s claims do more than shed light on a secret relationship.

If true, the testimony would also implicate Beijing in an ongoing corruption case against two Angolan generals close to the late Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos, whose tenure was plagued by widespread grift.

The generals are accused of corruption in connection with oil deals struck with Chinese entities in the post-war period, including China International Fund (CIF), one of Pa and Lo’s main companies. The case is considered “one of the biggest crimes in Angolan history,” according to Oxford University law professor Rui Verde.

It is just the latest large-scale corruption scandal to plague the sub-Saharan nation since the end of the civil war two decades ago.

“You had an opportunity for a fresh start in 2002 but it failed, and one of the reasons was the unaccountability of that Chinese money that came to Angola,” Verde told RFA.

Crude oil

Today China is Angola’s most important trading partner, but building that relationship was a slow, expensive effort. Long before Angola’s 27-year-long civil war drew to a close in 2002, Western nations had locked up most of the oil market.

For Beijing, which had backed the losing side, getting a toehold would have been no easy matter.

“Angola was a very oil-rich country, but the Chinese government could not enter. At that time, it was Britain, the United States, France and Italy that mainly controlled the country’s oil,” Lo told the Hong Kong court.

“So, at that time, the Chinese government, they hoped that we could, through other channels, get into this country to get the resources.”

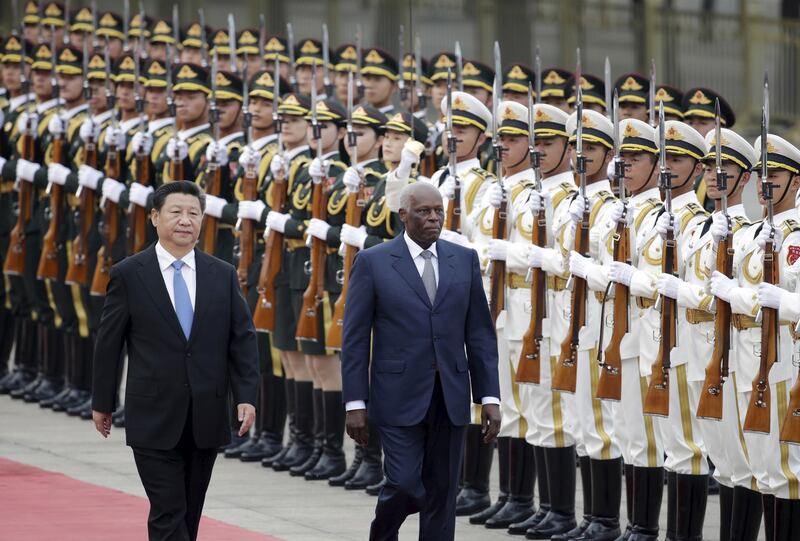

She and Pa were among those “other channels,” Lo claimed. After arriving in the country in 2002, the pair leveraged Pa’s longtime friendship with the country’s then-president dos Santos, to secure lucrative contracts to rebuild the country’s infrastructure and extract its plentiful supplies of oil. The deals were funded by loans totalling billions of dollars from Chinese state-backed banks.

Lo’s lawyer, William Wong, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Contact information for Pa, who is believed to still be in detention, could not be found.

In a separate ongoing case initiated in Angola in 2022, prosecutors allege that Lo, Pa and two Angolan generals used those contracts to embezzle hundreds of millions of dollars apiece. The prosecution is part of a raft of cases that have been brought by Dos Santos’s successor following his resignation in 2018.

Prosecutors allege that $1.5 billion of Chinese oil payments never made it to Angola, but were instead siphoned off to a Hong Kong company controlled by Pa, his associates and former high-ranking Angolan officials.

Prosecutors further allege that hundreds of millions of dollars that were supposed to build affordable public housing for Angolans instead ended up in accounts controlled by CIF.

Similar allegations have trailed CIF across Africa. In 2014, Pa was sanctioned by the U.S. government for financing intimidation of political opponents of Zimbabwe’s ruling party by the country’s intelligence service. And in 2017, a U.S. court sentenced Guinea’s former minister of mines to seven years in prison for laundering $8.5 million in bribes from the company.

In Angola, corruption has had a devastating effect on development – and so has indebtedness to Beijing.

Today, Angola owes Chinese banks $21 billion, equal to just under a third of the country’s annual economic output. Merely servicing the debt takes up almost half of the government’s budget. And yet ordinary Angolans have very little to show for it. More than 20 years after Pa and Lo turned up in Luanda, the United Nations estimates that 66.6% of Angolans are either living in poverty or in danger of falling into it.

Odious debt

With Angola struggling under the weight of Chinese debt, Lo’s revelations could provide a path forward, said Oxford’s Verde.

If Pa and Lo were not acting as private business people but as emissaries of the Chinese Communist Party, Angola’s leaders could file a request in arbitration court for the debt to be canceled under the doctrine of “odious debt.”

“There are two tests for it to qualify as odious debt. The money must have not been applied in the public interest and the creditor knew or had reason to know the money was not to be used in the public interest,” Verde told RFA.

“The question was, in the past, whether Sam Pa was acting as a private person or acting on express orders from the Chinese state,” he added. “If you find that he was acting on express orders from the Chinese state, then we have a problem concerning that.”

Hesong Shao, a spokesperson at the Chinese Embassy in Washington, told RFA by email that he was not familiar with the details of CIF’s deals in Angola. But, he added, China’s “partnership with African countries is always based on mutual respect, equality and sincere cooperation.”

“The projects China has undertaken in Africa and the broader China-Africa cooperation have contributed to Africa’s development and improved livelihoods across the continent,” Shao wrote. “The African people know that best.”

Pa and Lo’s extensive ties to the Chinese government have been well documented. A 2009 U.S. government report outlined their companies' “connections to the Chinese intelligence community, the public security apparatus, and state-owned enterprises.” However, other parts of the Chinese government appeared keen to distance themselves from Pa, according to leaked diplomatic assessments.

Uneasy bedfellows

Lo’s testimony suggests that the Chinese government was wary of getting into bed with Pa from the start. She recalled that in the early 2000s, Pa had been recently declared bankrupt and was ineligible to act as the shareholder or director of a Hong Kong company.

“Sam Pa was deeply in debt and his passport was confiscated by the government at the time,” Lo testified. “Internationally, he had participated in toppling or supporting some African countries, and he has some enemies.”

Pa’s debts and less-than-spotless reputation made his patrons in the Chinese government nervous, Lo testified. But his “upper-level connections in Angola” meant “the country was willing to use him” all the same.

However, their patronage came with conditions. One demand in particular came from the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s powerful economic planning agency, which insisted that Lo have practical control over the relevant companies.

“As long as he cooperated with me, he would have the policy given to him by the Chinese government and the funds would be given to him,” Lo told the court. “The total amount of these funds should be calculated as tens of billions of dollars.”

Edited by Abby Seiff, Jim Snyder and Boer Deng.