U.S. lawmakers and Chinese democracy activists marked the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre on Tuesday with a message that Congress had always stood together with Chinese dissidents, even if some presidential administrations had not.

In two separate events at Congress, the Congressional-Executive Commission on China and the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party remembered the lives lost during Beijing's repression of student-led pro-democracy protests in June 1989.

The violent crushing of the protests saw People's Liberation Army soldiers kill hundreds and perhaps thousands of young people pushing for democratic change, and led many of the survivors to be forcibly outcast from society in the decades since.

Standing outside the Capitol building at a gathering hosted by the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, former House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said the world's memory of June 4, 1989, was being kept alive by bodies like the select committee itself.

McCarthy, who was ousted from his role in an internal Republican Party revolt in October after less than two years as speaker, said the creation of the House Select Committee in January 2023 was one of his proudest achievements while head of the legislative chamber.

“It speaks volumes to the world about where America stands,” McCarthy said of the committee. “There’s no question between party – between majority or minority – where we stand about Tiananmen Square and where we stand about freedom around the world.”

"I'm proud that we will never hide back, and we'll stand with the man in front of the tank. We will honor him, everywhere we go," he said.

Uyghurs, Tibet and Hong Kong

McCarthy's predecessor as House speaker, Nancy Pelosi, told the gathering that Congress always worked to support dissidents in China, and recalled her own experience being chased out of Tiananmen Square after unfurling a commemorative banner there in 1991.

“We as Americans must speak out for human rights in China, because if we don't, because of commercial reasons, we lose all moral authority to speak out about human rights,” Pelosi said, calling China’s government a “very, very violent system that is getting worse.”

Congress standing up to China’s rights abuses in the decades since the massacre and amid the country’s increasing economic clout, she added, was a tough “test of our resolve” as lawmakers – but one that had been passed “in a bipartisan and bicameral way.”

“Whether it's about the plight of the Uyghurs, the destroying of the culture, religion or language of the Tibetans, the violation of rights of people across China … [or] what's happening in Hong Kong,” she said, both major parties had “stood the test” on human rights.

Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, the lead Democratic lawmaker on the select committee, said that the example set by McCarthy, a Republican, and Pelosi, a Democrat, proved lawmakers were united in their stance.

“Today we say in one voice, in a bipartisan fashion: No more silence,” he said, pledging that Congress will “stand for freedom” in China.

“No more silence about the Uyghurs in Xinjiang,” he said. “No more silence about Tiananmen Square. No more silence about the cultural genocide in Tibet. No more silence about the political persecution that countless others are facing today in the People's Republic of China.”

Presidential failure

Inside Congress, Sen. Jeff Merkley, a co-chair of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, told a separate hearing that his commission itself was the product of a battle between Congress and previous U.S. administrations over China policy.

“The massacre of peaceful protesters by their own government spurred a decade of debate here in Congress about whether the U.S. should condition trade relations with China on improvement in human rights,” Merkley said, adding that Congress had made its position clear.

President Bill Clinton’s decision to admit China into the World Trade Organization in 2000, Merkley said, was only approved by Congress after a deal was struck to create the commission, which he called “a bicameral, bipartisan watchdog” on Chinese rights abuses.

Some witnesses were more scathing of past U.S. policy.

Fengsuo Zhou, a student leader during the Tiananmen Square protests who now lives in the United States, said that the U.S. government had ultimately not stood up for human rights in China when it counted.

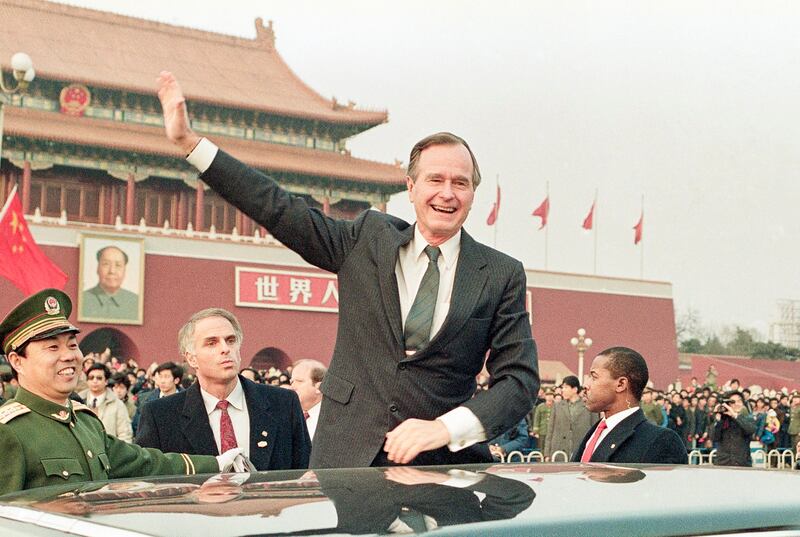

President George H.W. Bush had failed the Chinese people, he said, by openly condemning the crackdown while also quietly sending his national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, to China to relay that Washington's main priority was preserving its ties with Beijing.

“The whole world watched as the Chinese government turned against its own people,” Zhou told the hearing. “Yet President Bush sent a special envoy to inform the butcher of Beijing, Deng Xiaoping, of the support of the U.S. government, even after the senseless massacre.”

Bush’s muddled response had set China “on the trajectory of ever increasing political repression and human rights violations” and emboldened Beijing to act with impunity, Zhou said.

“That is why later, this very regime would put Uyghurs in concentration camps, would force Tibetans into self-immolation and would deprive Hong Kong of its freedom,” he said.

“If a regime can use tanks in broad daylight to kill its own people and still enjoy the support of the most democratic country in the world, there's no limit to what it could do.”

Edited by Malcolm Foster.