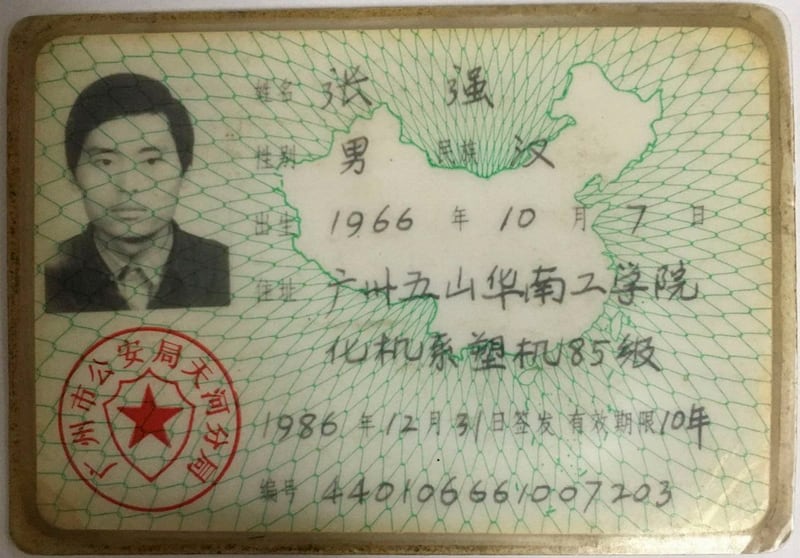

When thousands crowded into Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989 a show of public grief for late ousted Premier Hu Yaobang, kickstarting weeks of student-led protests, Zhang Qiang was a student at the South China University of Technology.

Zhang, who once marched at the head of a group of students to protest at the gates of the Guangdong Provincial People's Government, is now homeless, ostracized by society and abandoned by his family.

He has no fixed abode, nor even an ID card in a country where pretty much anything requires one.

Unlike the better-known names of the 1989 student movement -- Wang Dan, Wu'er Kaixi and Chai Ling, for example -- few will ever hear his name.

Yet there are hundreds, possibly thousands like him, according to activists who have been tracking the nationwide program of prison sentences and other forms of official retaliation meted out to idealistic youngsters because of their involvement for a few brief weeks in the summer of 1989.

Zhang still remembers the sense of outrage he and his classmates felt when Chinese Communist Party leader Deng Xiaoping declared martial law in Beijing on May 19.

"We thought this was a violation of the constitution and of the law, and would bring disaster down on this country," Zhang recalled.

So he marched at the front of a group of students to the provincial government, and was designated a "ringleader" by the authorities, a label that was to affect his life for decades to come.

Told to leave

While official retaliation was delayed for a few months, when it came, it was brutal.

"On Oct. 10, 1989, the South China University of Technology made a decision to tell me to drop out," Zhang said. "Neither the president, vice president nor the director of education signed -- they just put an official stamp on it and told me to leave the university."

Zhang's teachers put in a good word for him, and he eventually graduated in 1990 and even found a job. But a prolonged dispute with the university over his household registration, or "hukou," was never resolved, leaving him without a national ID card in 1996.

That meant he couldn't be employed any more, except as a casual laborer.

"Factories need people to load and unload goods, so I often do this kind of work," Zhang said. "They don't check your ID or your household registration."

A “hukou” is a key document entitling a person to government services and is required for marriage, education for their children and myriad other official processes.

As a result, Zhang was unable to marry or register his son. The impasse prompted his girlfriend and son to leave in 2010.

Zhang tried to resolve the Kafkaesque tangle with frequent visits to plead his case with the university, the local police and the local courts, but all three institutions just passed him around between them.

Eventually, the local police looked into the matter, and informed him in 2015 that the university had canceled his household registration back in 1994 – but hadn't informed him.

Now, he sublets an apartment from a friend, but has no official footprint at all.

"In a world where the current people are in power, I don't even have the right to eat or sleep, which is terrifying and evil," he said.

Covering up

Up in Beijing, Li Hai was a graduate student in philosophy at Peking University and took a central role in the student union throughout the Tiananmen Square protests.

He was allowed to graduate relatively unscathed, but noticed that students were generally allowed to get off more lightly than regular citizens who had openly supported them or resisted the People's Liberation Army on the night of June 3-4.

"They gave the students their enthusiastic help and support, and made great sacrifices, and they accounted for the majority of deaths,” Li told RFA Mandarin in a recent interview.

While the fate of high-profile figures like Wang Dan and Wu'er Kaixi dominated global headlines, the Chinese government was busy covering up the sheer scale of political prosecutions of ordinary civilians in the years following the crackdown.

Li spent about four years trying to keep track of them all, eventually building a list of 522 names of people convicted of "rioting" in the spring of 1989 that activists said is far from exhaustive.

In the aftermath, high-profile student protesters like Wang Dan got four years for "counterrevolutionary rebellion," but ordinary Beijing residents were sentenced to eight to 10 years in jail for doing very little.

"Most of them were young, and most had families, wives and children, so it was harder for them,” he said.

The authorities eventually got wind of Li's list, and sentenced him to nine years' imprisonment in 1995 for "leaking state secrets."

In one case reported to RFA Mandarin, 34-year-old intellectually disabled sanitation worker Wang Lianxi handed some matches to someone else while in a crowd of people who blocked the advance of People's Liberation Army tanks towards Tiananmen Square.

Despite the fact that Wang lacked the mental capacity to give any account of what he did or why he did it, he was handed a death sentence alongside seven others who allegedly burned military vehicles during the civilian resistance.

While Wang's sentence was later reduced to 20 years in recognition of his intellectual disability, he still remained in prison until July 2007.

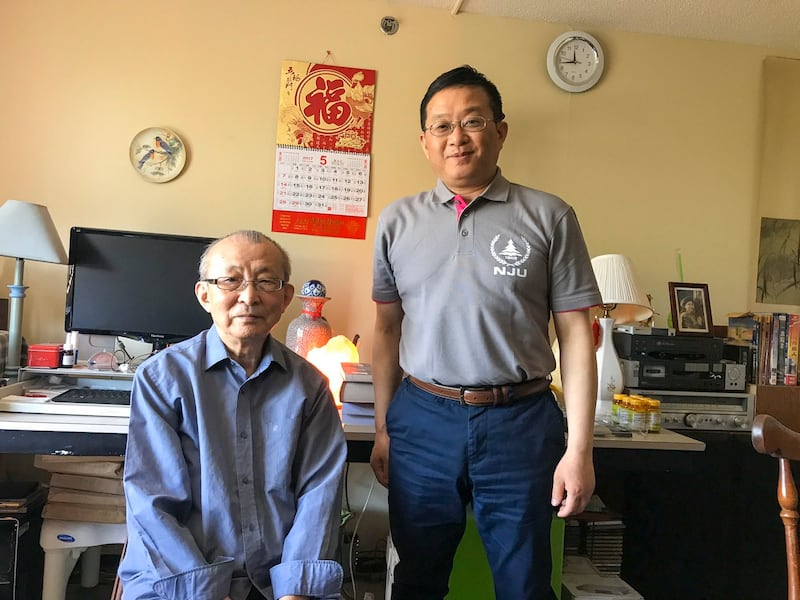

But he was never rehabilitated, and was incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital by his local neighborhood committee ahead of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, according to former psychiatrist Xu Yonghai, who spoke to RFA Mandarin after visiting Wang in a Beijing care home on May 15, 2024.

‘Tragically unlucky’

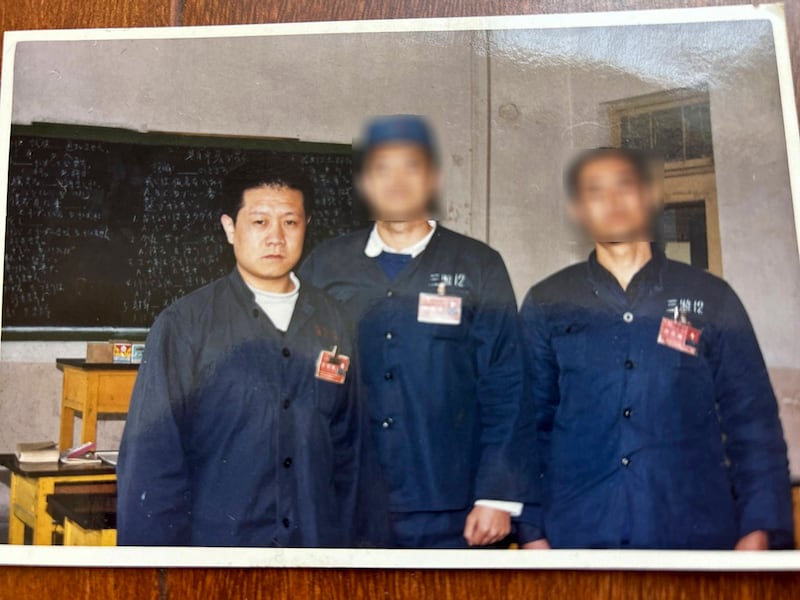

Netherlands-based Jiang Fuzhen was a worker in the eastern port city of Qingdao in 1989, and served an eight-year prison term for "counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement" after he posted an open letter criticizing then-Premier Li Peng at the Qingdao Ocean University.

Following his release in 1994, Jiang set out to find others who had been similarly treated.

He soon found that many had it far worse than he did.

"It was just a feeling I had that these people were wronged, and their lives made miserable," Jiang said. "They got such heavy sentences."

"To be honest, a lot of them didn't even have any political goals in mind -- they were just tragically unlucky," he said.

Wang Juntao, who chairs the U.S.-based China Democracy Party, said it's hard to find an exact figure for the numbers who were persecuted in this way.

The Tiananmen Square massacre and the student movement that preceded it remain forbidden topics under the Chinese Communist Party to this day.

"Even if we were to track down these people to tell us about this part of history, they may not want to," Wang said. "Some of them were tortured in prison, and were very scared after they got out."

"Some might have died if they didn't plead guilty," said Wang, an intellectual who served a 13-year jail term for being one of the "black hands" behind the student-led movement, told RFA in a recent interview. "Even if they pleaded guilty, it would be hard for them to give interviews to foreign organizations."

Many continued to be socially ostracized long after their release, even by people within the pro-democracy movement they had fought to support, Wang said.

"A lot of people wanted to distance themselves from so-called chaotic elements in the wake of June 4, 1989, meaning the people who took part in what the Communist Party said were riots and unrest, to prove that they were peaceful, rational and non-violent compared with the cruelty of the Communist Party," Wang said.

Impossible to investigate fully

Zhou Fengsuo, executive director of the New York-based Human Rights in China, said his organization has been compiling lists of political prisoners since the 1990s, and that the list provided by Li Hai was far from comprehensive.

"It's impossible to carry out a systematic investigation, of, for example, how many people were affected in any given province, or city or county," Zhou said in a recent interview.

Zhou thinks it's entirely possible that as many as 100,000 people were politically persecuted in the wake of the Tiananmen protests.

He gave the example of an acquaintance -- now based in New York -- who was a high school teacher at the time of the 1989 protests.

"He was deprived of his urban household registration and sent back to the town of his birth," Zhou said. "This kind of situation is very common, and has a huge impact on these people's lives."

"Some people make it through, while others don't, and continue to live in hardship."

Fears of being ‘disappeared’

Li Hai has been unemployed since he got out of prison in 2004. He told RFA Mandarin jokingly that his job is now to be persecuted.

"It means constantly avoiding the police, who harass me at my door," Li said. "One year, they came to my home 16 times. Sometimes they went away again, and sometimes they stayed, on one occasion, for more than six months."

Li also fears being "disappeared" at any time by the authorities.

"It's impossible to live a normal life," he said.

While some of the survivors of the Tiananmen crackdown managed to avoid the political taint that attached to many others, going on to lead successful lives or emigrating overseas, they are still in the minority, activists told RFA.

Former Beijing worker Liu Jiwei, who served a six-year jail term for "counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement" after he took part in pro-democracy protests in his native Shandong province, lived in fear from the day of his release in 1995 to the day he left China in 2017, he told RFA.

"For the whole of those 20 years I lived in China, I was like a lamb to the slaughter, tied to the bench with the knife likely to fall at any time, and powerless to do anything about it," Liu said. "You're under their control the whole time."

Now, Liu is wary of returning to China, for fear he will be forced to live in Shandong again.

Zhu Liquan was a graduate student in the department of philosophy at Nanjing University in 1989, and briefly served as chairman of the Nanjing University Student Union.

He was imprisoned during the 1989 crackdown, and went back to finish his studies following his release.

But everywhere he turned, he found obstacles to living a normal life.

"You may care about the world, but the world doesn't care about you, and the [Chinese Communist] Party won't give you any opportunity to show off your talents," Zhu told RFA.

Zhu eventually emigrated to Canada in 2020, and still follows events back home with passionate interest.

"Sometimes I tell my friends that the same hearts still beat in our chests as did back in 1989," he said.

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.