For transgender women in China, transitioning can feel like a mythical quest, a fresh obstacle arising just after one has been cleared.

Treatments are expensive, difficult to obtain and can require years of fighting unwilling doctors, red tape and familial disapproval.

In recent months, a difficult process has become even harder, according to Chinese trans women who spoke to RFA. In December, the Chinese government banned on onlines sale of cyproterone acetate, a widely used antiandrogen drug, and estradiol, a widely used estrogen drug.

The drugs are used in hormone therapies for a range of issues like prostate cancer and menopause. Both are needed for people who were born male to transition to female.

The government says the restriction was part of a process to add new safeguards to China’s relatively free-wheeling online drug market. But the ban is creating another problem for trans Chinese women: Many can’t find access to medicine through legitimate channels at all, driving them deeper into a black market where they are vulnerable to being scammed.

The situation has compounded a mental health crisis already gripping the community, leading to a rise in the number of suicides, trans women, known colloquially as “medicine girls,” told RFA.

As one of them, “Mel”, put it: "There's no way to survive. We can't survive. People are dying every day.”

Already difficult

It took Mel three years from the moment she walked through the doors of the hospital to obtain a certificate of diagnosis to begin the transition process to actually acquire it at 23. Without the approval of her immediate family, she had to travel overseas to have gender-confirming surgery.

Mel, like other trans activists quoted in this story, requested to be identified by a pseudonym to protect herself from abuse and potential questioning by the Chinese police.

Being a transgender woman in China poses challenges in almost every aspect of life, she said – from discrimination in school and work, to the hardship of the physiological transition itself.

Treatments are expensive, and the process is costly in other ways. After Mel changed the gender on her ID card, the money for her social security, medical insurance and housing provident fund were removed. She needed to borrow money in order to make up for the loss.

But Mel’s hardships are less stark than those faced by other Chinese transgender women, she said – most are not even able to complete the transition process and have to rely on smuggled medications purchased online.

But since December, “the [new drug] policy directly blocked the way, leaving no way out,” Mel said.

Sales ban

Some transgender activists who spoke to RFA said they believe the new restrictions, which were imposed by the National Medical Products Administration, specifically target transgender people, while others speculated that they may be related to China's efforts to reverse its population decline by encouraging childbirth.

Five other drugs that were banned alongside cyproterone acetate and estradiol are either contraceptives or abortion pills.

Chinese authorities have not explained their reasoning behind the changes in any detail, as often happens with policy shifts in the country. In the documents accompanying the ban, the NMPA stated that the listed drugs are "high-risk" and are prohibited in order to "ensure the public to take drugs safely."

In 2021, Chinese media reported on a mother who discovered that her 15-year-old son was secretly purchasing and injecting hormone drugs to attempt gender transition, believing that he had been "lured by bad people" from the "medicine girl" online chat room.

Local police set up a special investigation team after the mother reported her son.

Regardless of the intent, the trans community has been deeply affected by the tighter controls on online sales.

Trans activists told RFA they have observed an increase in suicides since the ban’s implementation, and pleas for help have emerged in online chat rooms and social media posts where transgender women find support.

"There has been a marked increase in cases [of suicide], far more than in previous years during the same time period," said “Hanlianyi,” a trans activist who provides shelter and other forms of assistance to transgender women in China.

Greater acceptance, but hardships remain

In some ways, China has become a more accepting place for transgender people. There is a greater awareness of the issues they face, and even sympathetic stories from the country's controlled media outlets.

There is no official data from the government on the number of transgender people in China.

In a 2014 article published in The Lancet medical journal, five Chinese surgeons estimated that there were approximately 400,000 transgender men and women in the country and suggested that less than 800 patients have been treated in the past 30 years.

In 2018, doctors at Peking University Third Hospital opened a transgender treatment clinic, followed in 2021 by Children's Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai.

But trans people say they still face widespread discrimination, as trans people do in other countries, including the United States.

In China, students with gender dysphoria can be suspended for being non-gender conforming, and trans adults have a hard time finding work. Trans people say they are routinely subjected to police and online surveillance due in part to the government's suspicion of minority groups.

Nearly 93% of the respondents to the National Transgender Health Survey Report, released by the advocacy group, Beijing LGBT+, in 2021, said they had attempted to obtain a diagnosis related to gender dysphoria in China reported varying degrees of difficulty.

Researchers found a higher rate of suicide attempts, anxiety and depression levels, and psychological stress in the transgender community versus the general population. Among the survey respondents, 71.7% were found to be at risk of depression.

The mental health issues registered in the survey have been made worse, trans women told RFA, by the online drug sale ban.

‘Please help’

Trans women find support through platforms including QQ and on Twitter and Telegram, which are banned in China but still accessible with a VPN.

RFA learned of the crisis sparked by the online drug sales ban through social media accounts and online pleas for help.

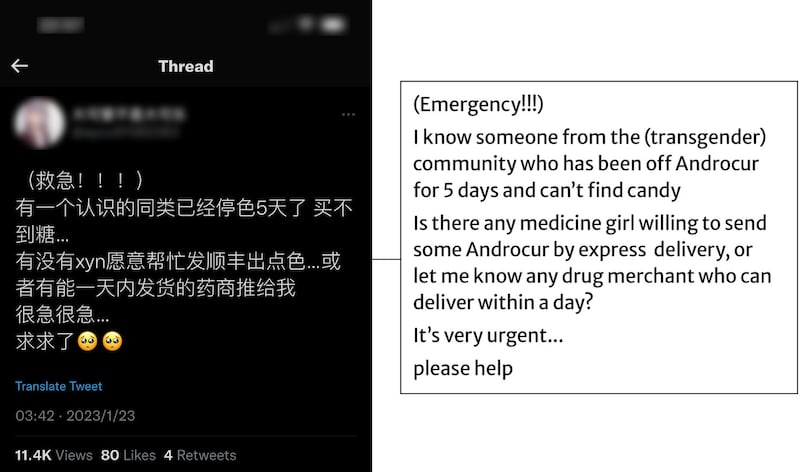

“Emergency!!! I know someone from the (transgender) community who has been off Androcur for 5 days and can't find candy,” a Jan. 23 Twitter post from a transgender woman said. “It's very urgent ... please help.”

Androcur, an antiandrogen medicine produced by Bayer, is illegal to import but is sometimes smuggled into the country. The nickname “candy” refers to androgen blockers and estrogen pills in general.

(RFA is not disclosing the account handle as these accounts can be subject to reprisals, such as being scrutinized by police surveillance.)

People with prescriptions theoretically can still purchase their medicine in pharmacies, but trans women say they often face resistance when doing so. Some pharmacists refuse to fill prescriptions for female hormone drugs – which are used in a variety of endocrine treatments – if the purchaser’s ID card refers to them as male, sources said.

Many trans people also prefer the privacy of online purchases where there is less risk of having to endure humiliating encounters with pharmacists or other customers.

Dubious drug merchants

With little alternative, transgender women in China are turning to questionable online sellers that claim to have smuggled drugs from overseas, despite the ban.

“Mika,” a transgender woman who has undergone gender reassignment surgery but still relies on estrogen, said online dealers charge around 300-400 yuan ($43-57) per box for Androcur, which can last for a little over a month.

But as the demand rises, more scammers are disguising themselves as drug merchants to con people out of money, only to send fake pills or nothing at all.

The consequences for trans women can be deadly. One of Hanlianyi’s friends took her own life after paying about 1,200 yuan ($172) for drugs that were never delivered, she said.

"Being cheated is often the last straw that breaks the camel's back," she said.

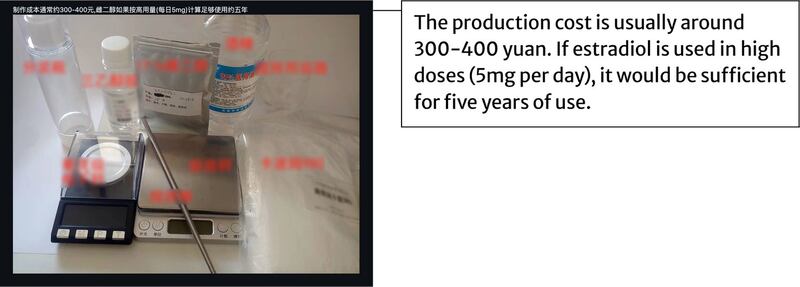

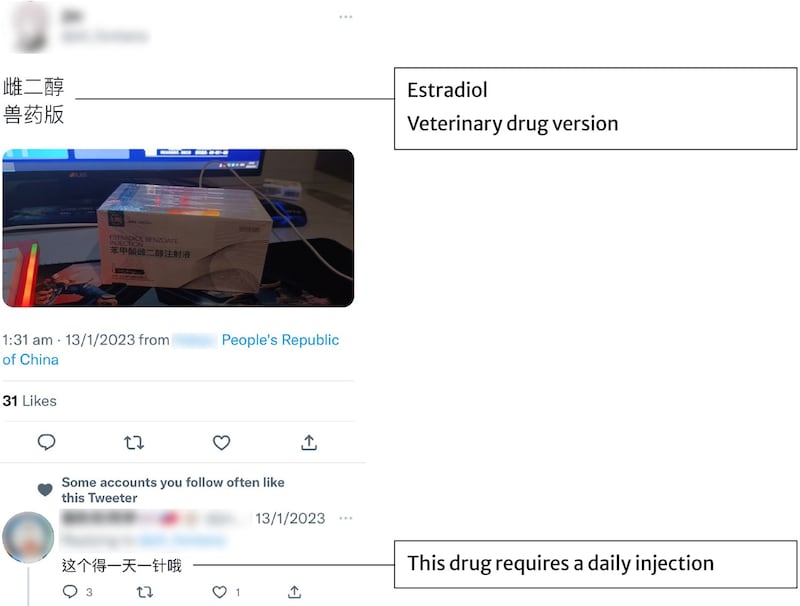

The trans women RFA spoke with said various strategies are passed around online in response to the drug ban, including taking veterinary hormone pills that are easier to acquire or trying to purchase the raw materials and fashion a facsimile of the medicine themselves.

In October “Hilda,” a transgender woman, started to use her own body as a lab to make a gel containing estradiol.

"I have achieved self-sufficiency and can also help some people," she told RFA.

Hilda said she knew about 10 other transgender women who began to make their own drugs between November and February.

Extreme responses

The obstacles trangender women face have led some to take action even more extreme, including self-castration, according to the women who spoke to RFA, news reports and social media posts.

“Felicity,” a transgender activist who grew up in China but now lives overseas, said before the recent online sales ban a woman live-streamed the process in a group chat, prompting a frantic online effort to send help to stem the bleeding.

Chinese media have also reported some transgender women in the country have operated on themselves or others.

In one case, a transgender woman helped another with surgery after having successfully removed her own testicles; in another, an individual was sentenced for illegally practicing medicine without proper qualifications.

"If a time comes when candy becomes completely unavailable, going abroad is not an option, and black market surgery in China is out of reach, I will provide a guide on self-castration,” a Feb. 11 tweet from a transgender woman said. “So, fret not, there is always a solution, right?"

In an Apr. 20 tweet, the woman said she had performed the self-castration and included a photograph of her on a bloody bed with surgical instruments nearby. But she added that she had almost died during the procedure and warned transgender women not to follow suit.

Activists Felicity and Hanlianyi told RFA that they fear the online sales ban will lead to more incidents of self-castration.

‘We can’t survive’

Previously, Mel said she has turned down interview requests from foreign journalists because she believed the Chinese government would address the problems.

Now, she’s begun to speak out.

She and her friends recently created a webpage to raise awareness of the consequences of the online sales ban, which is now in its fifth month.

It includes references to instances of transgender women being targeted by police and a running tally of people whom Mel says have taken their own lives since the start of the year.

The last count, posted on the page a month ago, was 91.