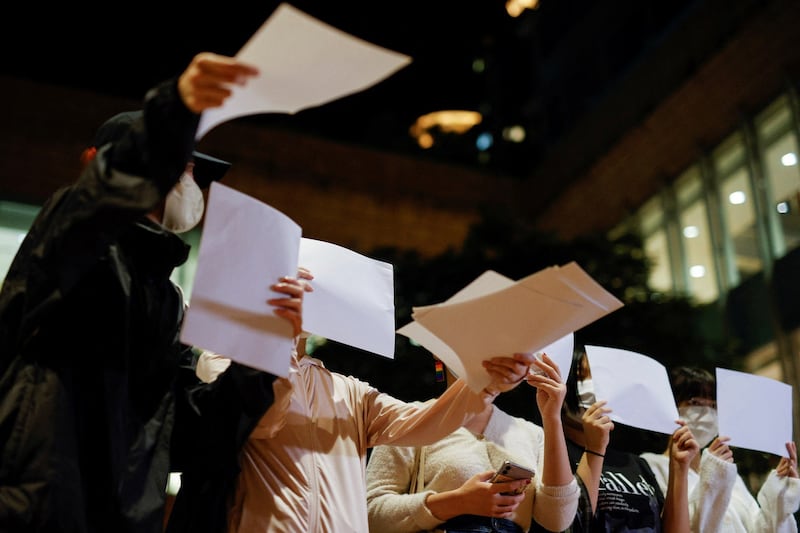

They have become a symbol of China’s recent wave of protests: Blank, white sheets of paper held aloft by demonstrators to signify their opposition to anti-virus lockdowns, censorship and restrictions on free speech.

As videos of crowds holding up paper sheets and chanting slogans flooded the internet last weekend, Chinese-language social media posts have come to call the demonstrations in more than a dozen cities the “white paper revolution.”

Authorities have since moved quickly to squelch the protests, arresting some demonstrators and sending university students home, in a bid to quickly snuff out the most overt challenge to Chinese leadership in decades.

Using blank sheets of paper as a symbol of protest is not new.

They were used during protests in the Soviet Union during the 1990s and in recent years in Russia and Belarus as well, Taiwan-based Chinese blogger Zuola told Radio Free Asia.

"In the current climate in China, you can be told off by the government for saying anything at all," Zuola said. "It's the ultimate kind of performance art protest -- by holding up a blank sheet of paper, you are saying that you have something to say, but that you haven't said it yet."

"It's very contagious, so everything started holding up these blank sheets of paper to show dissatisfaction with the social controls imposed by the Chinese government, with their political environment and with [controls on] speech," he said.

Pent-up anger

The protests were sparked by public anger at the delayed response to a deadly fire on Nov. 24 in Urumqi, the regional capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, that has been widely blamed on COVID-19 restrictions.

The incident, which left at least 10 people dead, tapped into pent-up frustrations of millions of Chinese who have endured nearly three years of repeated lockdowns, travel bans, quarantines and various other restrictions to their lives.

Videos swirled around the internet showing people in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities holding the white pieces of paper above their heads, demanding an end to the strict “zero-COVID” limits. Protesters also began to call for greater freedom of expression, democratic reforms, and even the removal of President Xi Jinping, who has been closely identified with the rigid policies.

According to an unverified document circulating on social media, officials in major cities were being told to take steps to control the supply of ubiquitous white printer paper, with a major stationery firm suspending online and offline sales.

Compared with the Post-it notes that formed the "Lennon Walls" of Hong Kong's 2019 protest movement, which showcased huge mosaics of diverse messages and creative personal expression, the blank sheets of paper are a more ironic reference to government controls and censorship, analysts said.

Striking a chord

Veteran Taiwan social activist Ho Tsung-hsun said the white paper revolution had quickly spread across the country, indicating it struck a chord with a wide variety of protesters in China.

"Some people pasted blank sheets of paper next to a statue of [late revolutionary Chinese writer] Lu Xu, and under Xi Jinping slogans," Ho told RFA.

"Some students sang the Internationale in their dorms at night, while others took their guitars to sing it on the streets, with blank sheets of paper pasted next to their guitars," he added, referring to the communist anthem.

"In Wuzhen, Zhejiang, some young women sealed their mouths shut, handcuffed themselves and held up blank sheets of paper," he said.

Ho added that people quickly started using other white items following reports that the sale of A4 paper – the typical size of printer paper in China and other countries – was being restricted by the authorities.

"I'm more inclined to call it the white revolution, because people have been very creative about expressing themselves through white objects, since reports emerged online that it was now impossible to buy paper, that sales had been restricted in a lot of places," he said.

"If they restrict sales of white paper, then other white materials and objects can be used, such as white cloth or white paint," Ho said.

Some online accounts have started replacing their avatars or profile photos with white backgrounds, while social media users have used the hashtags #whitepaperrevolution and #A4revolution to show support for the protests, alongside selfies holding blank sheets of paper in the streets or posting them anonymously on bulletin boards and in corridors, cafes and parks.

‘We want dignity and freedom’

A news and commentary account that uses the handle @citizensdailycn across several social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter said the white paper movement was "the revolution of our generation."

"We want to say what they don't want us to say: We want dignity and freedom," it said in an apparent rallying call opposing controls on speech and information, as well as the restrictions of the zero-COVID policy.

The Urumqi fire has coincided with a growing realization that the circumstances in China as it relates to COVID restrictions are unusual compared with other countries, according to Zuola.

"Since the start of the World Cup, the Chinese people have been discovering that no other country is taking [the] Omicron [variant of COVID-19] seriously," Zuola said.

"People are also angry that Sinovac and other [Chinese] vaccine companies won their licenses through bribery, and over the government collusion with business that has made it impossible to roll back pandemic restrictions over the past three years," he said.

Feeling their pain

"Then there was the lone protest by Peng Lifa," he said, in a reference to the Oct. 13 "Bridge Man" protest banners hung from a Beijing traffic flyover. "All of this has been fermenting for some time; it hasn't happened overnight. There has been a sense of long-running grievance over internet censorship in China, too."

When the Uyghur residents of the apartment block died in a fire after screaming to be allowed to leave the locked-down building, everyone in China felt their pain, he said.

"They were shouting that they were all from Urumqi, that everyone was a victim of the disease control measures, and that they couldn't allow those people to be left to die in silence," he said.

Ho believes there is also a mute reference to ballot papers -- meaningless in China, where all "election" candidates must be pre-approved by the government -- in the use of sheets of printer paper.

The blankness of the sheets also echoes the lack of clear aim or unified leadership during the weekend's protests.

"A movement without a leader is what those in power fear the most," Ho said.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster