Coastal vegetation and estuaries are collectively a greenhouse gas sink for carbon dioxide, but methane and nitrous oxide emissions counteract some of the uptake, new research showed Monday.

The international researchers looked into estuaries – tidal systems/deltas, lagoons and fjords – and surrounding coastal vegetation, including mangroves, salt marshes and underwater seagrasses.

Such coastal ecosystems release or absorb carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). The researchers found the net effects of these ecosystems in offsetting greenhouse gas (GHG), said the report published Monday evening in the journal Nature Climate Change.

According to the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the key GHG emitted by human activities globally in 2019 includes 75% CO2, 18% CH4, and 4% N2O.

“Understanding how and where greenhouse gases are released and absorbed in coastal ecosystems is an important first step for implementing effective climate mitigation strategies,” said lead researcher Judith Rosentreter, a senior research fellow at Southern Cross University in Australia.

“For example, protecting and restoring mangrove and salt marsh habitats is a promising strategy to strengthen the CO2 uptake by these coastal wetlands.”

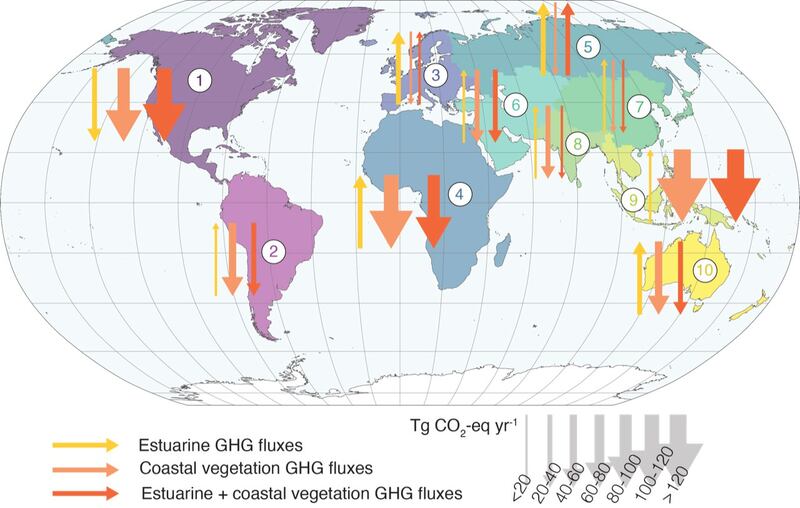

The researchers looked into a dataset of observations on 738 coastal sites from studies published between 1975 and the end of 2020 to quantify CO2, methane, and N2O fluxes in estuaries and coastal vegetation in 10 world regions, including East and Southeast Asia.

They showed that the CO2-equivalent (CO2e) uptake by coastal vegetation is decreased by 23–27% due to estuarine CO2e outgassing, while total coastal CH4 and N2O emissions decrease the coastal CO2 sink by 9–20%.

Rosentreter said coastal wetlands, such as mangrove forests, coastal salt marshes, and seagrasses, release at least three times more CH4 than all estuaries worldwide.

Coastal wetlands, known as “blue carbon” wetlands, absorb CO2 and some N2O, making them a net sink for greenhouse gases when all three are considered.

Coastal regions worldwide have unique characteristics, such as climate, hydrology, and abundance, which influence the emission or absorption of GHGs.

The researchers said that minimizing human impact, such as reducing inputs of nutrients, organic matter, and wastewater into coastal waterways, can lower the release of CH4 and N2O into the atmosphere.

“In our new study, we show that when we consider all three greenhouse gases (CO2 + CH4 + N2O), eight out of the 10 world regions are a coastal net greenhouse gas sink,” Rosentreter said.

Coastal areas in Russia and Europe perform worst

The archipelagic region of Southeast Asia was the most robust coastal GHG sink due to its extensive and productive tropical mangrove forests and seagrass meadows, which take up large amounts of CO2, the research said.

Compared with other regions, Southeast Asia also has relatively few estuaries along its coasts, many of which are a source of CO2, CH4, and N2O, the report said.

North American salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrasses take up CO2, but not as much as Greenland’s fjords, responsible for most of the 40% of global CO2 uptake attributed to the glacier-formed inlet.

In East and South Asia, coastal vegetation CO2 sinks are reduced mainly by estuarine GHG emissions, making them moderate sinks.

“East Asia is contributing 34% of global salt marsh CH4 emissions despite its relatively small marsh coverage,” Rosentreter told Radio Free Asia.

Europe and Russia release more coastal GHG than they can take up from the atmosphere, due to sizable estuarine surface area and fewer wetlands, like mangroves, due to a colder climate that would otherwise take up large amounts of CO2.

Since the beginning of the industrial era, around the 1800s, atmospheric concentrations of CO2, methane, and N2O have increased by 47%, 156%, and 23%, respectively, and continue to grow at alarming rates due to anthropogenic activities, those caused or influenced by people, driving global warming,

In March, the IPCC said greenhouse gases released by fossil fuels and other human activity had “unequivocally caused global warming,” and the increase in average surface temperature was already contributing to climate and weather extremes around the globe, such as heatwaves and droughts and the intensity of rains and tropical cyclones.

The average temperature between 2011-2020 was 1.1 degrees Centigrade higher than 1850-1900. Last week, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said there is a 66% likelihood that the annual average global temperature, which has not crossed the 1.5 C threshold set by the Paris climate agreement, will be more than 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year.

The future role of coastal ecosystems as a sink or source of GHGs in each world region will depend on adopting best practices to reduce CH4 and N2O emissions while strengthening CO2 uptake, Monday’s report concluded.

Edited by Mike Firn.