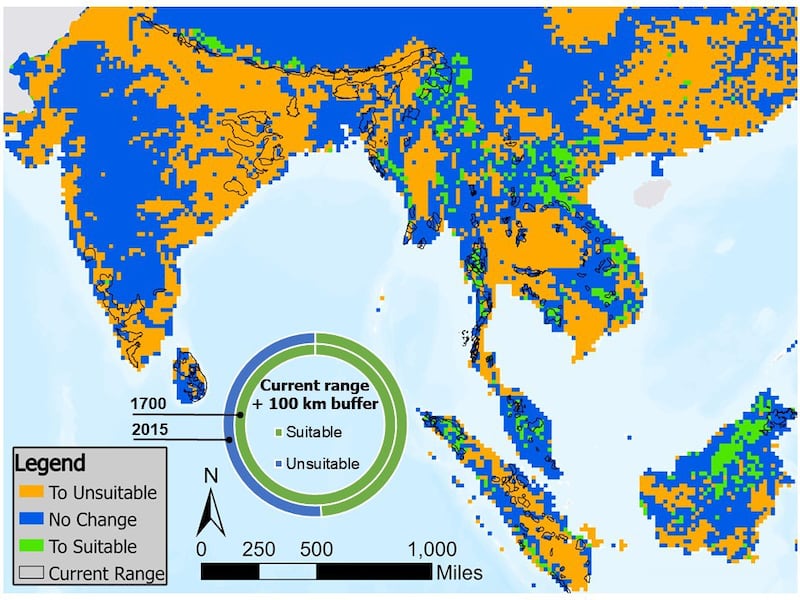

Across Asia, over 64% of the land suitable as a habitat for elephants historically has been lost in the past three centuries, a new study examining ecosystems in the continent said.

The estimated habitat loss between 1700 and 2015 amounts to 3.3 million square kilometers (1.3 million square miles) of land – slightly larger than India, the seventh largest country in the world – said the study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

“In the 1600s and 1700s, there is evidence of a dramatic change in land use, not just in Asia, but globally,” said the study’s lead author Shermin de Silva, an assistant professor of ecology at the University of California San Diego.

“Around the world, we see a really dramatic transformation that has consequences that persist even to this day.”

In the three centuries, the average habitat patch size reduced by 83%, from 99,000 to 16,000 square kilometers (38,224 to 6,178 square miles), the study found, while the area occupied by the largest patch in Asia decreased from around 4 million to 54,000 square kilometers (1.5 million to 20,850 square miles).

The most significant declines were observed in China, where around 94% of suitable elephant habitats were lost in the three centuries. It is estimated that the area decreased from 1 million square kilometers in 1700 to 65,189 square kilometers in 2015 (386,102 to 25,170 square miles).

In China, elephants have complete protection currently, and their numbers have slightly increased, from fewer than 200 to more than 300, in recent years.

According to Thursday’s study, India lost 86% of the suitable area for elephants, from 1.6 million to less than a quarter million square kilometers (617,763 to 96,000 square miles), followed by Bangladesh, where the area decreased by almost 72%, from 44,046 to 12,405 square kilometers (17,006 to 4,791 square miles).

In Southeast Asia, the study said the disappearance of highly suitable habitat in central Thailand was “particularly striking,” with much of it occurring between 1950 and 1990 in areas that have now become cropland.

It decreased 67%, from 480,413 to 158,331 square kilometers (185,488 to 61,132 square miles) in Thailand, which the study said reflects historic timber extraction, associated land-use conversions since the kingdom was never colonized, and the more recent expansion of industrial agriculture.

Even though swathes of forest remain in Thailand and neighbouring Myanmar, both have lower estimated elephant populations than expected based on their share of the suitable range, most likely due to timber and tourism.

In Myanmar, there was also poaching for the skin in the past decades. The researchers said captive elephants in those two countries likely outnumber wild elephants.

Two of the most critically endangered elephant populations are found in Sumatra and Vietnam with each losing more than half their suitable elephant territory.

Laos and Malaysia showed some net gain in areas outside the current range, where it is unknown whether elephants were ever present.

However, Borneo, the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia, gained in habitat area suitable for elephants. Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei share the island in Southeast Asia’s Malay Archipelago.

Human-elephant conflict could increase

The study’s authors contended that the current conflicts between humans and elephants could be attributed to the significant reduction in suitable habitat for the animal.

It could further escalate, they said, since the existing elephant populations might be facing more habitat shortages, primarily due to the nature of land-use by humans.

In 1700, all regions within 100 kilometers of the current elephant range were deemed suitable habitats. However, by 2015, the proportion had dropped to below 50%, the study said.

Conflicts between humans and animals are among the greatest threats to the long-term survival of some species, including elephants, said a 2021 report by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Wildlife Fund.

In India alone, 100 humans (up to 300 people in some years) and 40-50 elephants are killed during crop raiding each year, according to WWF.

The reduction of habitat ranges for various land-based mammal species due to human activities has been extensively documented in recent years. Climate change has further aggravated this decline, particularly in the last century.

An urgent need for sustainable land-use and conservation strategies is needed to avoid such incidents, the researchers said in Thursday’s study.

“We’re using elephants as indicators to look at the impact of land-use change on these diverse ecosystems over a longer time scale,” said de Silva.

There are around 44,000 Asian elephants in 13 countries, with more than half of them in India. Weighing up to 5,500 kilograms (12,000 pounds), they are the largest living land animal in Asia.

The animals have been listed as "endangered" in the IUCN's " Red List" of threatened species, because of a population decline of "at least 50% over the last three generations."

Asian elephants live in various habitats, including grasslands and rainforests that once spanned the breadth of the continent. Such areas were relatively safe before the 1700s.

The habitat loss since then coincides with the colonial-era use of land, including timber extraction, as well as agricultural intensification in Asia, according to researchers.

Using land-use data, they estimated the change in the spread and fragmentation of Asian elephant ecosystems in 13 countries between 850 and 2015. They then calculated the change to identify land that 300 years ago would have been suitable for elephants.

“We used present-day locations where we know there are elephants, together with the corresponding environmental features based on the [land-use] data sets, to infer where similar habitats existed in the past,” said de Silva.

Experts say present day protected areas may not provide sufficient space for elephant populations to thrive, since they may have roamed in larger areas in the past.

“In order for us to build a more just and sustainable society, we have to understand the history of how we got here. This study is one step toward that understanding,” de Silva said.

Edited by Mike Firn.