New findings from two scientific studies reveal that the environmental impact of the global rubber trade due to deforestation has been significantly underestimated, with Southeast Asian rubber production potentially causing up to three times more forest depletion than previously believed.

With more than four million hectares of forest, an area as large as Switzerland, lost for rubber farming since 1993, "the effects of rubber on biodiversity and ecosystem services in Southeast Asia could be extensive," said the report published on Wednesday in Nature journal.

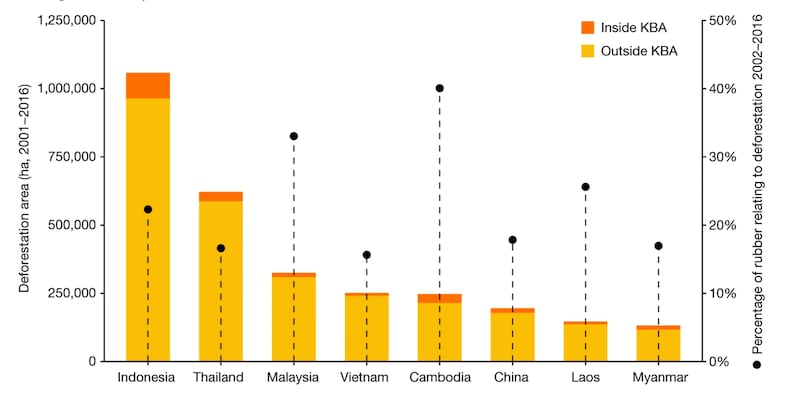

Mature rubber plantations spanned a combined area of 14.2 million hectares in Southeast Asia. Over 70% of these plantations were concentrated in Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Notable rubber-producing regions also included China, Malaysia, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos. Rubber plantations abandoned before 2021 were excluded from the study, even though they may have contributed to deforestation.

More than a million hectares of rubber plantations in Southeast Asia are established in key biodiversity areas, some of the most critical sites for the conservation of species and habitats globally, the report said.

Rising global demand for rubber is intensifying stress on natural woodlands and leading to a decline in biodiversity, according to researchers who used satellite data to produce high-resolution maps of rubber-driven forest loss and analyzed over 100 case studies.

Southeast Asia accounts for 90% of global rubber output.

Another review of case studies and analysis of recent trends in rubber area and yield also found that rubber is regularly linked to deforestation. It was published in Conservation Letters on Wednesday.

As demand grows and yields stagnate, continued deforestation for rubber is to be expected, lead author Eleanor Warren-Thomas warned.

“Some 2.7 million to 5.3 million hectares of additional harvested area could be needed to meet industry estimates of demand by 2030,” she said.

“It is critical that existing rubber producers are supported to improve their yields and maintain production, to avoid ongoing expansion of plantation area.”

‘Sobering’ result

Rubber, a crucial rainforest product, is obtained by tapping latex from specific trees native to the Amazon and now widespread in tropical regions. The collected latex is processed to boost flexibility and durability through heat treatment.

Rubber production’s link to deforestation was acknowledged before, but it was difficult to quantify the extent of this harm due to distinguishing it from natural forest cover in satellite imagery.

As a result, the issue received limited attention in assessments of losses from commercial plantations, according to Yunxia Wang, the study’s lead author in Nature.

“However, thanks to expanding earth observation and computing technology, there are increasing opportunities to map ‘difficult’ commodities. The results have been sobering,” she added.

Although rubber-related deforestation is prevalent, senior author Antje Ahrends expressed specific concerns about specific countries.

“In Cambodia, for example, over 40% of rubber plantations are associated with deforestation,” she said.

19% of that was in key biodiversity areas, according to research.

The Nature journal study said the rubber impact in Southeast Asia is still lower than that of oil palm, but not by a factor of 8 to 10 as previously suggested, but only by a factor of 2.5 to 4.0.

“With 70% of the world’s natural rubber yields destined for tire manufacture, demand is not likely to diminish, and the threat this poses to biodiversity should not be underestimated,” Ahrends said.

“In addition, while predominantly grown by smallholders with the potential to support livelihoods, rubber is also associated with land grabbing and human rights infringement in some countries.”

Both studies stress the importance of stopping rubber-related deforestation without marginalizing the 85% of smallholder farmers who are often less than 5 hectares in size who contribute to natural rubber production.

A new regulation is set to be implemented in the European Union next year, aiming to prohibit commodity importers from purchasing products that contribute to deforestation. It will include soy, beef, palm oil, wood, cocoa, coffee, and rubber.

Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.