Ski instructor Showkat Ahmad Chopan looks around at the brown, rocky mountain slopes around him in Indian-administered Kashmir – normally covered in snow at this time of year – and realizes he may not have any students this year.

“This is the first time I’ve seen such conditions in January, our peak snow season,” he said.

“Kashmir’s winters have always been our pride and joy. The snow not only blankets our valleys in beauty but is extremely important for tourism and the local economy,” said Showkat, 26, who has taught visitors at the famous Gulmarg ski town – one of the world's highest skiing destinations – since he was 15.

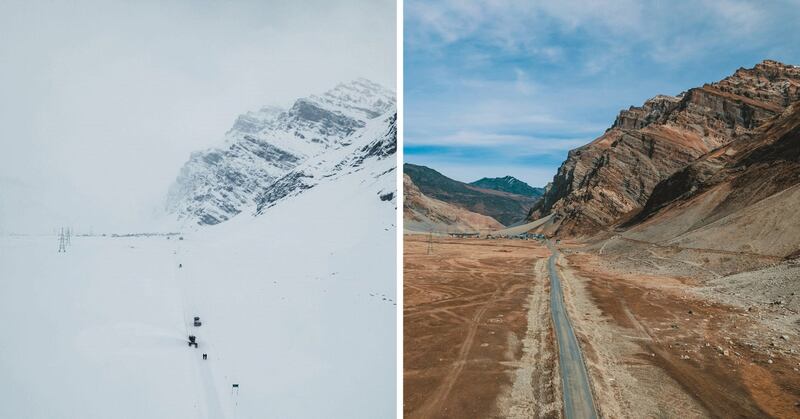

Warmer-than-normal temperatures and little precipitation over the past month have resulted in what experts are calling a “historical snowless dry winter” for not just Kashmir but the sprawling Himalayan region, from northern Pakistan to Tibet and Bhutan.

A combination of several weather phenomena are to blame: El Niño, the warming of Pacific Ocean waters, and a decline in Westerlies, winds that sweep cold air and moisture from central Europe, the India Meteorological Department said. Add to that broader climate change driven by an increase in greenhouse gases and warming global temperatures.

And the lack of snow could lead to water shortages for millions of people, experts warn.

The cryosphere – snow, ice, and permafrost – in the Hindu-Kush Himalayan region that stretches from from Afghanistan to Myanmar is the world’s most crucial water tower, serving as the water source for large parts of Asia.

“Winter snowfall is a lifeline for the Himalayan people for agriculture, irrigation, drinking water, recreation, tourism, entertainment, and of course recharging of glaciers, which are retreating rapidly,” said Sonam Lotus, director of the meteorological department in Jammu and Kashmir.

Economic impact

There’s a direct economic impact on local residents who rely on tourism income at this time of year.

“The scant snowfall has been alarming. Bookings, domestic and international, are canceled,” said Showkat, his voice tinged with worry.

“Most villagers are directly or indirectly affected, especially the hundreds of daily wage workers who depend on these couple of months’ earnings for their entire year,” he said.

Normally, temperatures during Chillai Kalan – Kashmir's harshest, 40-day winter period starting Dec. 21 – hover around -15 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit). But this month they've been between -4 to 12 C (24.8 to 53.6 F).

So far in January, there has been virtually no snowfall in the western Himalayas, and compared to previous years precipitation was down 79% in December.

Srinagar, the capital of Jammu and Kashmir state, experienced its warmest January day on the 13th, with temperatures rising to 23.6 C (74.4 F), surpassing the previous record of 17.2 C set in 1902.

Weather changes thousands of miles away are contributing to the lack of snowfall. El Niño, a rise in equatorial Pacific temperatures last year, reduces cold wave days. And wind patterns are changing.

“The climate of the Himalayan region is dependent on Westerlies, the prevailing winds that sweep in from Central Europe. They carry moisture; when they hit the big mountain ranges, they drop it as precipitation. But those Westerlies haven’t hit the region so far this year," said Joseph Shea, a professor of environmental geomatics at the University of Northern British Columbia in Canada.

“"The season is so much shorter in those Karakoram and Himalayan mountain ranges,” he told Radio Free Asia. “So if you don’t get those storms by December-January, by February, it may be too warm to start.”

A July 2023 study on western disturbances from 1980 to 2019 shows a marked reduction in this weather phenomenon, especially the severe storms, resulting in a roughly 15% drop in winter rainfall in northern India and Pakistan.

‘Devoid of snow’

Iftikhar Hussain, a filmmaker based in Kargil, the joint capital of Ladakh – a high plateau bordering Pakistan and Tibet – said this January resembles March, with unexpected vegetation growth, including blooming flowers and wild grass, highly unusual for the season.

He said that areas known for two meters of snow, frozen rivers and closed mountain passes for months during winter had little to no snow, with the pass open for public transport.

Drass, 60 kilometers from Kargil, is the coldest inhabited town in India – it’s called the “Siberia of India” – usually has piles of snow at this time of year.

“This year, it’s completely devoid of snow,” Iftikhar said, adding that he’s concerned for farmers who will face much drier conditions.

In Leh, the joint capital of Ladakh, water isn’t freezing. Pangong Tso Lake has not fully frozen even close to February, a stark contrast to its usual early December freezing in previous years.

“Ladakh at this time of last year… have had very good snowfall before Losar festival (mid-December) and several times after that, which resulted in good harvest for the season,” Konchok Stanzin, a local representative in the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council in Leh, told RFA.

In neighboring Himachal and Uttarakhand – west of Nepal – forests and hilltops are typically covered in snow around this time. However, according to the state government, there has been a sevenfold increase in forest fires compared to last year due to dry winter.

In Nepal, mountain fields are parched, with many regions lacking their usual snow cover. A local resident in Kalinchowk, the country’s only ski resort, said they received their first snow on Jan. 18, more than six weeks later than in previous years.

Typically, Nepal sees about 60 millimeters 2.5 inches) of rain during its coldest three months, from December to February, but it has recorded less than 2 mm this winter. It is shaping to be the driest, following last year’s similarly arid winter with only 12 mm of rain, the lowest in 15 years.

No white winter, no green summer

With peak winter almost over, the warmer weather concerns farmers and nomads, who are performing rituals and praying for snow, according to Stanzin.

“No whites in winter means no greens in summer,” the local adage goes.

“The hope for a green summer is slowly vanishing,” Stanzin added. “It is the first time in my life not to see snow in February, but we are still hopeful.”

The lower-than-usual snowfall across the Himalayan range has raised concerns among local residents and environmentalists alike as snow and ice water feed their rivers and lakes and provide a reliable source of meltwater in the warmer months.

Lack of snowfall will reduce the water supply and could exacerbate drought in the summer.

“We might recover from the tourism losses, but the real issue is water scarcity. If the high mountains don’t receive enough snow, there will be long-term effects,” Showkat, the ski instructor, told RFA.

Spanning thousands of kilometers and containing the world’s highest mountains, this region supplies water to major rivers like the Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus and Yangtze.

The Hindu-Kush Himalayan region is warming at a rate of 0.3 C per decade, much faster than the global average, while its glaciers are melting 65% faster since 2011 compared to the previous decade.

A 2019 study predicted a 90% decline in glacier volumes by the 21st century due to decreased snowfall, increased snowline elevations, and longer melt seasons.

Last week, the United Nations weather agency reported that 2023 was the hottest year on record.

“Even if you break up [the region] into central, western, or eastern Himalayas – they all show an increase… in average temperatures over the years,” Tenzing Ingty, a conservation biologist at Jacksonville State University in Alabama, United States, told RFA.

It is “going to get progressively hotter,” he said. As a result, the amount of snowfall, the number of days of snowfall and the number of days under the snow will decline, he said.

Additional reporting by Lobe Socktsang, Yeshi Dawa, Thinley Choedon for RFA Tibetan. Edited by Malcolm Foster.