Mysterious bottles full of rice, US dollars and memory sticks containing anti-North Korean content that showed up in the Han River around the South Korean capital of Seoul are the work of local North Korean escapee organizations, escapee activists told Radio Free Asia.

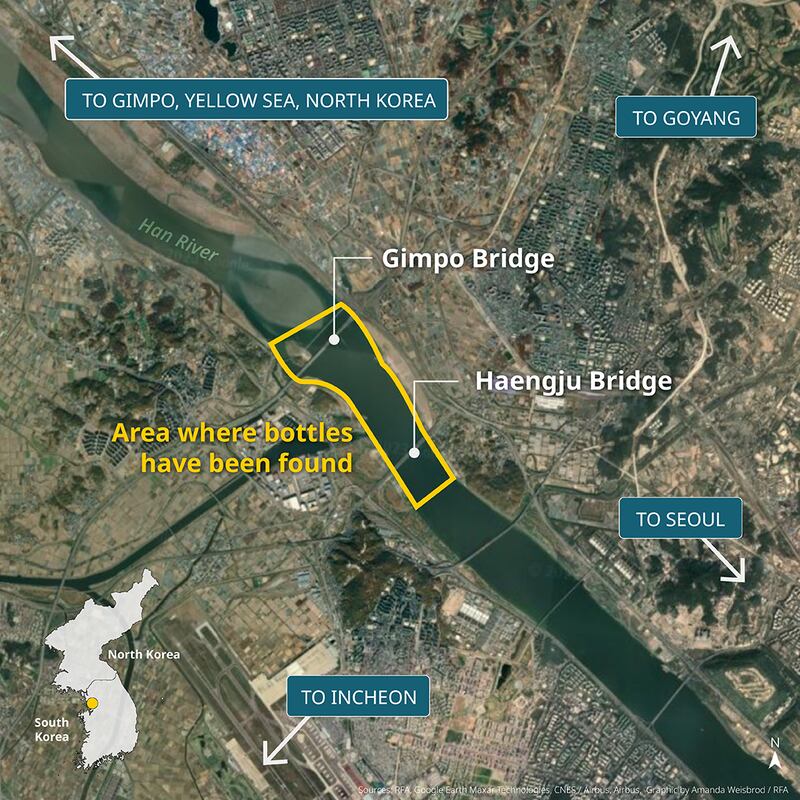

South Korea’s Yonhap News reported last week that fishermen working in the mouth of the Han are catching the plastic bottles in their nets. They frequently appear in the area between Haengju Bridge in the capital’s northwest and the Singok Submerged Weir just outside the city limits.

“Three years ago, similar plastic bottles used to come up, but then they stopped,” Yonhap reported a fisherman as saying. “They are recently being found again.”

The bottles are intended to follow the flow of the river into the sea current, which could potentially deposit them on North Korean west coast beaches.

South Korean police said they thought the bottles were sent by escapees who have resettled in the South and became activists. A North Korean rights activist, who requested anonymity for personal safety, confirmed this was the case to RFA’s Korean Service.

“Sending plastic bottles of rice was an activity of a group called North Korean Defectors Campaigning for North Korea's Liberalization, a so-called liberalization campaign,” he said in a phone call.

Questionable legality

Sending bottles to North Korea in this way is illegal in the South. The practice violates the relatively new anti-leaflet law which was passed in Dec. 2020, during the Moon Jae-in administration.

The law was intended to prevent escapee groups from sending hot air balloons across the border into North Korean territory to drop money, rice, flash drives, and thousands of anti-regime leaflets in areas where they could be picked up by North Korean citizens.

The administration saw the launches as an irritant in bilateral ties between Seoul and Pyongyang, but critics said the law violated freedom of speech rights enshrined in the South Korean constitution and allowed Pyongyang to veto what people in the South are allowed to say.

The anti-leaflet law remains on the books, and violators can be imprisoned for up to three years or be fined 30 million won (US$23,600).

But the current South Korean president, Yoon Suk Yeol, has said that the law was a mistake and written opinions drawing its constitutionality into question have been submitted to the country’s constitutional court.

The Ministry of Unification, meanwhile, maintains a cautious stance that residents should refrain from sending leaflets and balloons to North Korea for their own safety, but it acknowledges that there are unconstitutional elements of the anti-leaflet law.

The illegality of their activities is why members of the Liberalization Campaign group take care to hide their identities. They also send hot air balloons to North Korea with their most recent launch on April 9.

The activist said that since releasing the 12 balloons on April 9, the group has sent bottles down the Han three times. In addition to the rice and money, the bottles also include a small Bible and a flash drive with USB messages for North Koreans who find them. He said that the group plans to continue sending the bottles when weather conditions are ideal.

If the sea current is flowing the right way, more than 90% of the bottles will make it to North Korea, said Park Jeong-oh, the CEO of Keunsaem, another escapee group that sends bottles to North Korea. The bottles are usually picked up by North Korean fishermen.

After the Yoon administration took power, North Korean escapee organizations in the South have been more active in their attempts to send items into North Korea.

On May 5, a group called Fighters for a Free North Korea sent 20 large balloons loaded with Tylenol and vitamin C pills, anti-regime booklets and leaflets, from Ganghwa island off the country’s west coast. In October last year, they launched eight such balloons.

The group’s chairman Park Sang-hak, told RFA on May 8 that he intends to continue these types of activities until the day that North Koreans find freedom from their enslavement to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

Translated by Claire Shinyoung Oh Lee. Written in English by Eugene Whong. Edited by Malcolm Foster.