North Korean women are becoming more and more reluctant to have children due to poor economic conditions and food insecurity, rejecting government propaganda aimed at increasing the plummeting birthrate, sources in the country told RFA.

Though the declining birthrate is a problem on both ends of the Korean peninsula, the reasons behind it are drastically different.

South Koreans are avoiding having children in the face of rising housing prices, high supplemental educational costs, and grueling work-life balance ratios. North Koreans, however, worry about having more mouths to feed while the country continues to struggle with food security.

“The biggest reason why women in North Korea are reluctant to give birth to children is that they are not in a normal environment to raise kids due to a lack of food and basic necessities caused by economic difficulties,” a resident of the city of Hyesan, in the northern central Ryanggang province told RFA’s Korean Service June 13.

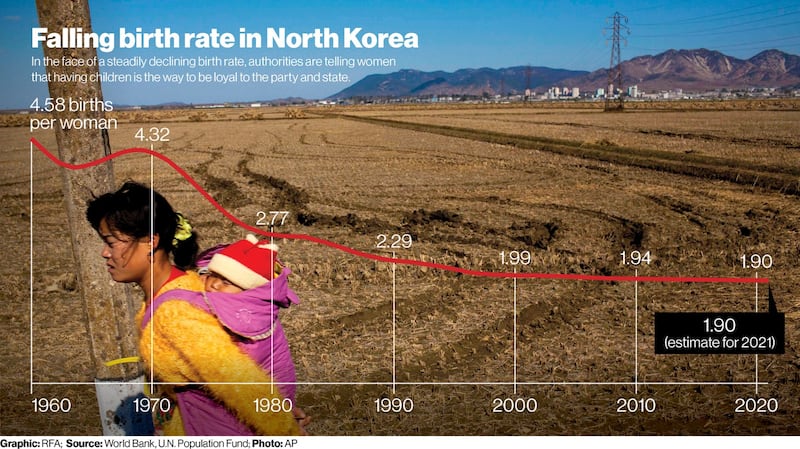

According to data from Statistics Korea, the South Korean National Statistical Office, the population of North Korea in 2019 stood at 25.25 million. The UN estimated that the fertility rate in North Korea between 2015 and 2020 was 1.91 children per woman of childbearing age and trending downward each year, and lower than the rate of 2.0 for the previous five-year period.

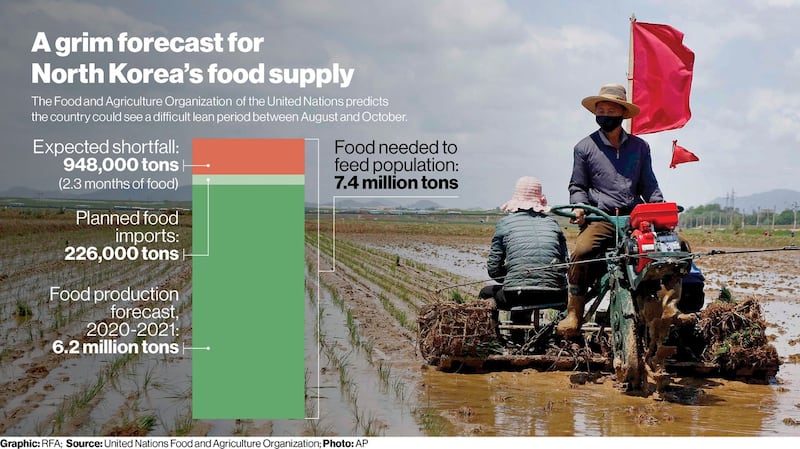

The North Korean economy has been devastated by international nuclear sanctions and the closure of the border and suspension of all trade with China since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic in Jan. 2020.

RFA previously reported that the government has been telling the people to prepare for conditions worse than the 1994-1998 famine, which killed millions of people, as much as 10 percent of the North Korean population by some estimates.

U.N Special Rapporteur on North Korean Human Rights Tomás Ojea Quintana warned in a report in March that the closure of the Sino-Korean border and restrictions on the movement of people could bring on a “serious food crisis.”

“Deaths by starvation have been reported, as has an increase in the number of children and elderly people who have resorted to begging as families are unable to support them,” said the report.

Against this backdrop, women in North Korea are ignoring their government’s expectations and thinking more realistically about motherhood, according to the Hyesan resident, who requested anonymity for security reasons.

“At one time, the country praised mothers with many children as ‘heroines’ and praised their fertility as ‘patriotic,’ but the burden of raising children is so great that most families now acknowledge that they have to be more in control of pregnancy and childbirth to match with their means,” said the source.

To encourage women to have more children, the state has introduced several benefits for mothers of three or more children, including exemptions from forced mobilization, the country’s chief way of procuring labor for government projects, according to the source. The exemption also extends to children of such families.

“But people think that anyone who says they want to have three children because of the multi-child benefit provided by the state is a naive fool who doesn’t know anything,” the source said.

“When I asked a woman I knew who had one daughter if she had any plans to have a second child, she sighed, saying it was difficult to raise even one child in the current situation. She said she wanted to give a younger brother to her daughter, but she emphasized that having another child in such a situation would be painful not only for the family, but also for the child being born,” said the source.

Another source, a resident of the city of Chongjin in northeastern North Hamgyong province, told RFA June 13 that many women there have resigned themselves to the idea that they will have a single child or none at all.

“Women of childbearing age all sneer at the national propaganda encouraging them to have kids,” said the second source, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

“A teacher working at an elementary school in Chongam district, here in Chongjin, complained that there were more than 30 children in each class only seven or eight years ago, but now 20 children are considered a large class,” said the second source.

In North Korea, many women are the breadwinners for their families, as their husbands work at their assigned jobs for a nominal salary that is not enough to live on. The women must run family businesses to cover living expenses, leaving little time for much else.

“The reality is that women are responsible for their family’s survival and they are engaged in business activities and don’t have time to think about pregnancy and childbirth,” the second source said.

“These days, women of childbearing age also have difficulty conceiving because they are malnourished or they come down with diseases from working too hard, so that’s adding to the fertility problem.”

The second source said that without government support to help families raise children, the birthrate will only continue to decline.

“The country is encouraging us to give birth to many children without suggesting a way to solve our economic distress,” the second source said.

“How can young women think of giving birth to many children when it’s common to see infants suffering from malnutrition right before our very eyes?”

A report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA) said that North Korea's current fertility rate of 1.9 is lower than the world average of 2.4 and lower than the Asia-Pacific region's rate of 2.1, which is also the rate needed to maintain a country's current population. North Korea ranked 119th out of 198 countries listed in the report.

Reported by Jeong Yon Park for RFA’s Korean Service. Translated by Jinha Shin. Written in English by Eugene Whong.