North Korea is among 45 countries worldwide requiring external assistance for food to feed its population due to economic constraints and an expected poor harvest this year, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

In its quarterly report "Crop Prospects and Quarterly Global Report Food Situation" issued on Sept. 30, the FAO evaluates the grain production and food situation of low-income countries around the globe.

The 47-page report notes that high inflation rates and challenging macroeconomic environments are aggravating food insecurity conditions globally, particularly in low-income food-deficit countries.

“In the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, persisting economic constraints, exacerbated by expectations of a reduced 2022 harvest, may worsen the food insecurity situation, with large numbers of people suffering from low levels of food consumption and very poor dietary diversity,” the report says, using the country’s official name.

Chronic food shortages and dependency on international food assistance are nothing new in North Korea, a diplomatically isolated country weighed down by its centrally controlled planned economy and its juche, or self-reliance philosophy, and plagued by harsh weather.

North Korea has been classified as a country lacking general access to food and in need of external food aid since the FAO began its research on the topic in 2007

The FAO forecasts that North Korea, along with Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka will suffer from food shortages this year due to lower-than-average grain yields.

The report also pointed to worsening weather conditions, such as poor rainfall, as one of the reasons for North Korea’s below-normal agricultural production.

In addition, as the worsening economic situation in North Korea continues, imports of essential agricultural products and humanitarian goods have fallen sharply, making North Korea’s 26 million people feel more vulnerable to food security this year.

In particular, the FAO pointed out that the decline in the nation’s grain harvests is causing most of the population to suffer from low food consumption and poor diets.

However, like the previous report, the current document did not specify the amount of grain that North Korea must import due to food shortages there.

In its December 2021 report, the FAO estimated that North Korea needed more than 1.06 million metric tons of food imports to make up for food shortages between November 2020 and October 2021.

Problem lies with Kin Jong Un

In light of the current situation, U.S. experts say Pyongyang’s rejection of food aid from other countries has worsened the severe food shortage.

“[North Korean leader] Kim Jong Un has refused nearly all offers of aid, especially from both the U.S. and South Korea,” David Maxwell, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies, told RFA on Monday.

“Unfortunately, there is nothing the U.S., South Korea, or the international community can do about the food shortages in North Korea unless Kim Jong Un is willing to accept aid in accordance with standard procedures for distribution transparency and accountability.”

“The Korean people in the north are suffering solely because of the deliberate policy decisions by Kim Jong Un to prioritize nuclear weapons and missile development over the welfare of the North Korean people,” Maxwell said. “The international community wants to relieve their suffering, but the problem lies solely with Kim Jong Un.”

Soo Kim, a policy analyst focused on national security and policy issues in the Indo-Pacific at the RAND Corporation, agreed that the Kim regime is the greatest obstacle to getting international food aid to North Koreans.

“Kim does not prioritize the lives of his people, and he is willing to let the North Korean population suffer as long as it does not adversely impact his leadership and interests,” she said.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) forecast in its "Rice Outlook: September 2022" report that global rice production will increase while North Korea's rice production will fall further this year compared to 2021.

The USDA forecast that North Korea will produce 1.36 million metric tons of dehusked rice this year, 38,000 metric tons less than the amount produced in 2021.

The agency also predicted that the country’s rice imports this year will reach 180,000 metric tons, up 30,000 metric tons from 2021.

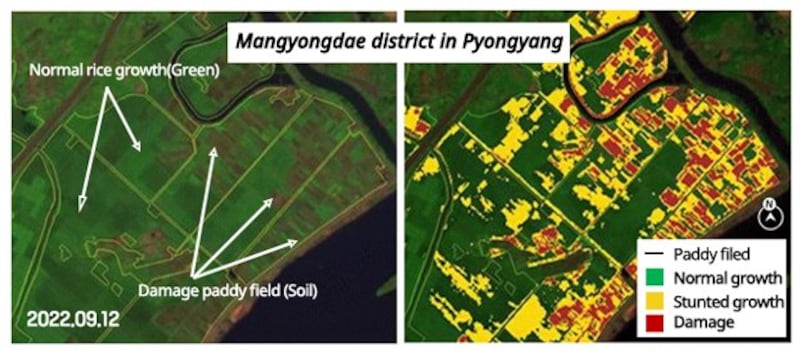

A South Korean scholar’s analysis of satellite images of North Korea appear to back up findings and forecasts in the two reports, indicating expected significant decreases this year due to flood damage in about 30% of the country’s rice fields.

Chung Songhak, deputy director of the National Land and Satellite Information Research Institute at Kyungpook National University in South Korea, cited images of Pyongyang's Mangyongdae district captured by European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2B satellites on Sept. 12, showing several areas of damaged rice fields where the soil has been exposed.

By region, rice growth at cooperative farms in Pyongyang’s Mangyongdae district was the lowest, followed by Pongsan and Unpa counties in North Hwanghae province, Sunchon city in South Pyongan province, and Chaeryong county in South Hwanghae province, Chung said.

Four factors have affected rice farming in North Korea this year, he said.

“First, the lack of water due to high temperatures and the drought from spring earlier this year,” Chung said. “Second, there was not enough manpower mobilization for the cooperative farms due to the [coronavirus] quarantine and movement control of residents.”

“Third, it rained heavily after rice planting was over,” he said, citing record-levels of heavy rains damaging agricultural lands, with paddy banks collapsing and rice braids washed away.”

“Fourth, the damaged paddy fields could not be restored, and rice did not grow well,” he said.

Translated by Leejin J. Chung for RFA Korean. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.