North Koreans whose family members have escaped the country and resettled in South Korea are being banished to rugged rural areas, in the latest punishment for citizens vilified as traitors by the Kim Jong Il regime, sources in the country told RFA.

Ryanggang province, located along the border with China in the north of the country, meted out the punishment to 30 households in mid-July, shortly after the central government changed escapees’ designation from “illegal border crossers” to “traitorous puppets.”

According to a previous RFA report, the change in terminology coincided with a decision to more fiercely crack down on the families for their relatives’ escape from the country’s sputtering economy and harsh political system.

“On July 13th, The State Security Department selected defectors' families and exiled them to remote mountainous areas,” a resident of Ryanggang province told RFA’s Korean Service on condition of anonymity for security reasons.

“They selected families who had two or more family members defect to South Korea. Thirty households were simultaneously relocated,” the source said.

Both North and South Korea use politically charged terms to refer to escapees, and many international media outlets render these terms as “defector” in English.

Rights organizations make a distinction between defectors, who were part of the government or military at the time they escaped, and refugees, who were not involved in the country’s power structure and left for economic reasons or to flee persecution.

The latest punishment follows previous anti-escapee campaigns, including when North Korea forced citizens to attend mass rallies to denounce the escapees as traitors, arrested people for speaking positively about escapees in public, and arrested families for having phone contact with, or receiving money from, members of their household who escaped to the South.

In many areas close to the border with China, remittances from escaped family members are an important source of income for many families, and they are usually able to get out of punishment by bribing authorities when they are caught. But it has now become more difficult to avoid the consequences.

The plan for Ryanggang province to banish refugees’ families to remote areas had been in the works for several months, the source said.

While the original plan would have punished all families related to escapees, the authorities decided to narrow their net.

“They reduced the target size to those families in which two or more members had defected … because too many families would have to be expelled for having just one family member who defected from North Korea. That target population is too large,” said the source.

“The expelled families went through a joint investigation by the State Security Department and judicial authorities under the presence of the head of their neighborhood watch unit. They confiscated the family’s cash and valuable household items, such as electronics,” said the source.

The banished families encompass people from all walks of life, according to the source.

“A couple in their 70s was selected for exile because two of their grandsons defected. Others included parents whose sons or daughters escaped, or children left behind after their parents fled to South Korea first,” said the source.

“Those to be exiled did not know where they were being sent until the moment they left. They kept the final orders secret, fearing that if their close neighbors learned where they would be, they might forward that information to their family members in South Korea,” the source said.

The relocation order only affected people whose family members escaped after 2010, another Ryanggang resident told RFA on condition of anonymity to speak freely.

“An industrial truck owned by a company came by in the early morning and transported the exiles somewhere else, and they brought with them only minimal cooking tools,” said the second source.

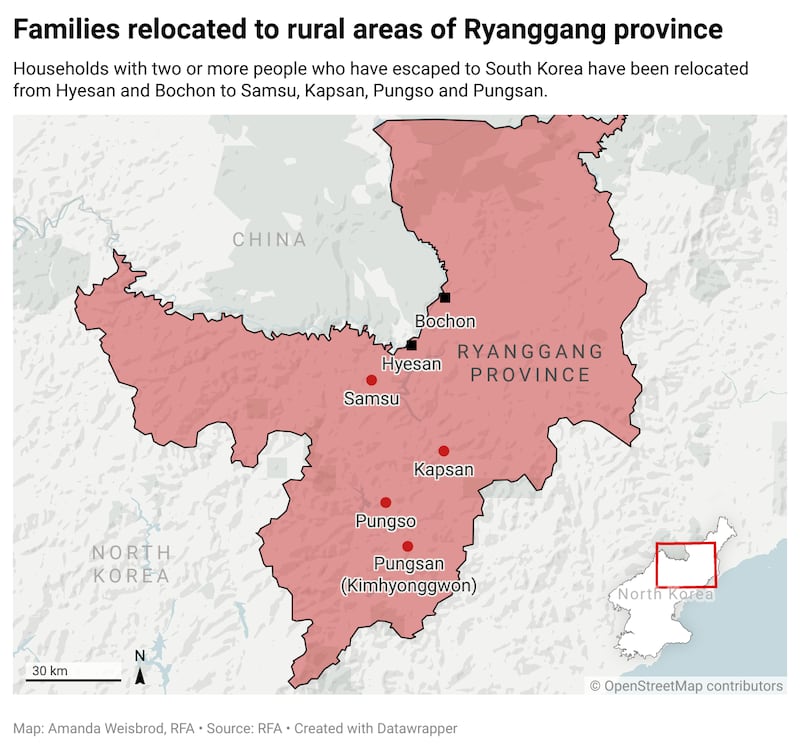

“A driver in a shoe factory and forestry machinery business reported that he took a banished family from Bocheon to exile in Pungso,” the second source said.

The source said that exiled families are commonly dropped in obscure villages –Samsu, Kapsan, Pungso, and Pungsan—lying somewhere between 12-75 miles from Hyesan, a city of more than 190,000 people and the administrative center of the province.

“These areas have several security guard posts, so it is difficult to wander freely out there,” the second source said.

The second source confirmed the earlier RFA report that escapees are now referred to as “traitorous puppets,” indicating a renewed crackdown on their families. The term "puppet" is often used to refer to the South Korean government, implying its illegitimacy.

“The residents blame the authorities for exiling the families, who can just barely make a living with the help of their defector family members,” the second source said.

“The authorities took this measure to prevent the inflow of external information over the telephone”

According to statistics from the South Korean Ministry of Unification, at least 1,000 refugees from the North have arrived in South Korea every year since 2002, peaking at more than 2,900 in 2009.

Under Kim Jong Un’s rule, though, refugee arrivals in the South decreased to slightly more than 1,000 in 2019, then dropped off sharply in 2020, likely due to increased border security during the coronavirus pandemic.

Only 229 North Korean refugees made it to South Korea in 2020, 63 in 2021, and 11 through March 2022.

Translated by Claire Shinyoung O. Lee. Written in English by Eugene Whong.