An exhaustive, 10-year survey of 6,351 North Korean escapees about their former lives in the isolated country paints a bleak picture: Food and energy are both scarcer, and government surveillance and crackdowns are stricter.

Women now play a more elevated role in families and society – though not because of a heightened sense of equality, but rather out of economic necessity, those interviewed said. They have become the main breadwinners, setting up stalls in makeshift markets that now are the main source of food and other basics for daily life.

The results of the report, compiled between 2013 and 2022 by the South’s Unification Ministry and released Tuesday, opens a window into the lives of ordinary North Koreans, and clearly indicates that the quality of life has worsened since Kim Jong Un came to power in 2011 after the death of his father.

Han Songmi, who was 19 when she escaped in 2011, is one of more than 30,000 people who have fled the North over the years. Now living in South Korea, she imagines what her friends and peers are experiencing, since she has virtually no way of communicating with them.

“They are probably in their late 20s now, and they are probably living with more anger than they did back then,” said Han, who was not interviewed for the survey.

When she lived in North Korea, Han said she and her friends were aware that the government controlled every aspect of their lives, but they were not allowed to discuss such things freely.

“The authorities were cracking down on kids for their clothing and hairstyles,” she told RFA Korean. “The kids would be saying ‘We can’t do this’ among ourselves, but we couldn’t say that in front of adults. Adults would always say, ‘Be careful, your parents can get arrested because of you.’”

Authorities also restricted the kinds of clothes people could wear.

“We had to wear a black skirt and a white top, but I witnessed some in Pyongyang being cracked down on for wearing South Korean-style jeans or wearing earrings,” she said.

Economic shocks

The survey results show economic conditions in North Korea have worsened, and that women have become main providers for their families.

Until the 1990s, people could rely on the government to provide their food under a rationing program, but this changed dramatically when the Soviet Union collapsed and aid from Moscow dried up.

The centrally planned economy could not cope with the sudden shock, resulting in a famine between 1994 and 1998 that killed more than 2 million by some estimates in what has become known as the “Arduous March” – a defining period in the country’s history.

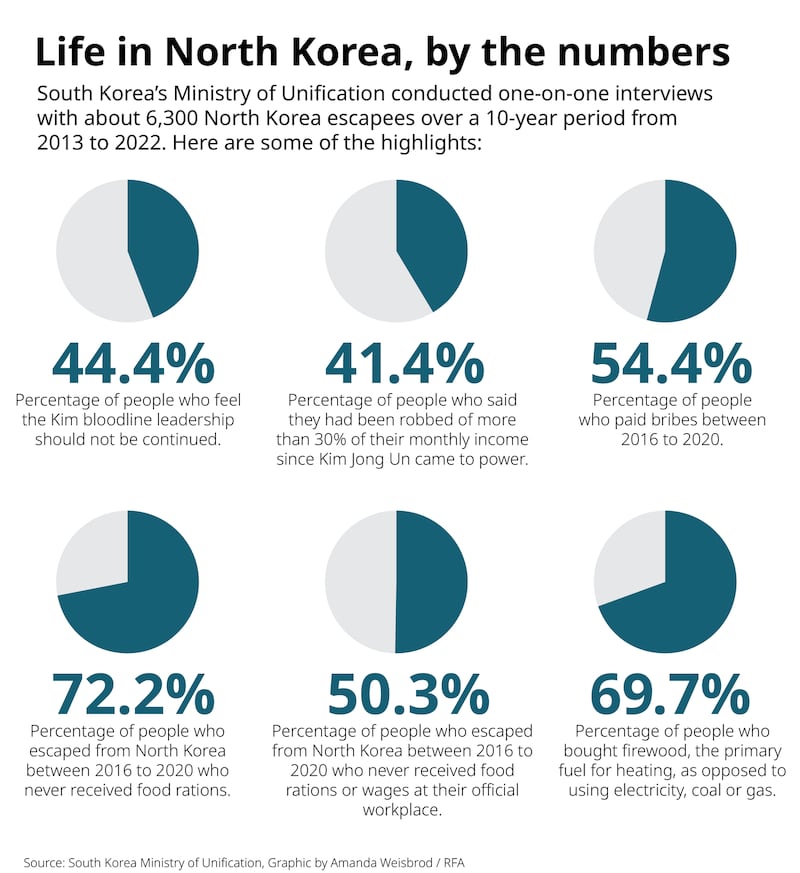

The rationing system became no longer viable. The Ministry of Unification’s report showed that among respondents who fled North Korea between 2016 and 2020 more than 72% of those interviewed said they had never received food rations.

The system changed somewhat to allow people to access a rationing system at their government-assigned jobs. People could expect to be paid a salary that they could then use to buy food at discounted prices.

‘Barking dogs’

But in reality, state-assigned jobs became less and less a means of support.

Among those who fled before 2000, 33.5% said they had received neither food rations nor wages at their official workplace. For those who fled between 2016-2020, some 50.3% said the same.

With government jobs – mostly held by men – paying almost nothing, housewives have had to make money to survive, and have started running tiny businesses in markets, buying and selling things such as vegetables and packaged foods and various products smuggled in from China.

Since Kim Jong Un began his rule, 70.5% of the respondents said they have had to rely on these local markets for survival, the survey showed.

The salaries paid to men, meanwhile, have become so miniscule that the men are unable to provide for their families, so men are increasingly referred to by slang terms like “barking dogs” or “daytime lamps,” suggesting they are insignificant and generally useless.

“Usually, most women made a living by selling things in the market,” said Han. “Although their husbands worked at a company, the company did not provide rations or pay much. I think women’s voices gradually grew louder from that generation onwards because women had to feed their families.”

Corruption

Since North Korea’s economic collapse, corruption has become more of a problem, the survey showed.

While the ordinary people operate side-businesses to make ends meet, those in power use their status or position for economic gain, by collecting a percentage of these side-business’ profits, or by extracting bribes.

Of the survey respondents who escaped since Kim Jong Un came to power, 41.4% said they had been robbed of more than 30% of their monthly income, and among those who escaped between 2016 to 2020, 54.4% said they had paid bribes.

“As the authorities' crackdowns intensify, residents have no choice but to pay bribes as part of whatever they are doing to make a living,” said Lee Hyun-Seung, who escaped from North Korea in 2014 and settled in the United States. She was not one of those interviewed in the survey.

“Because we do not have economic freedom, those who engage in economic activities cannot receive legal protection,” she said. “That’s why we pay bribes and receive protection or avoid punishment from people in power.”

Power shortages

Ordinary people also have less access to electricity, the survey showed, since the cash-strapped government prioritizes industry over the good of the people.

Prior to 2000, most residents got an average of 5 hours and 42 minutes of electricity per day in their homes. Since Kim Jong Un came to power, they’re getting about 90 minutes less, an average of 4 hours 18 minutes, the survey found.

“I can’t imagine how the situation can be worse now than when I escaped,” Kim Sookyoung, who escaped North Korea in 1998 and settled in the United States, told RFA.

“When I lived in North Korea, the day electricity came on was like a holiday,” said Kim, who was not among those interviewed by the Unification Ministry. “When the electricity came on, all the residents in my apartment building shouted with joy. The light itself was just a joy.”

She said there were some days when the electricity did not come on at all. So people would charge batteries so they would have light during those days.

“The first thing I did when the electricity came on was to charge the battery,” she said.

Heating the home in the dead of winter has also become more of a challenge. In years past, people could rely on electricity or gas for heat, but these days it’s all about firewood.

More than 69% of the respondents to the survey said they purchased firewood to heat their homes because it was more reliable.

Leadership

The survey asked several questions about the country’s leadership by members of the so-called Paektu bloodline, made up of national founder Kim Il Sung and his descendants, which include his son and successor Kim Jong Il and his grandson, the current leader Kim Jong Un.

The report said that 743 of the respondents were asked whether they supported the continuation of the Paektu bloodline leadership system prior to their escape from North Korea. Of those, 44.4% said they were against dynastic rule, while 37.8% said they supported it.

Support for the regime has waned over the years. Among the respondents who escaped from North Korea before 2011, only 29.9% said they had had negative feelings about the regime, whereas 52.6% of those who escaped after 2012 felt the same way.

Among those escaped between 2016 to 2020, this figure climbs to 56.3%.

During a press briefing on Jan. 29, Unification Ministry spokesperson Koo Byoung-sam said that it is not easy to confirm concrete signs of North Korean residents’ dissatisfaction with the regime they live under.

Translated by Claire Shinyoung Oh Lee and Leejin J. Chung. Edited by Eugene Whong and Malcolm Foster.