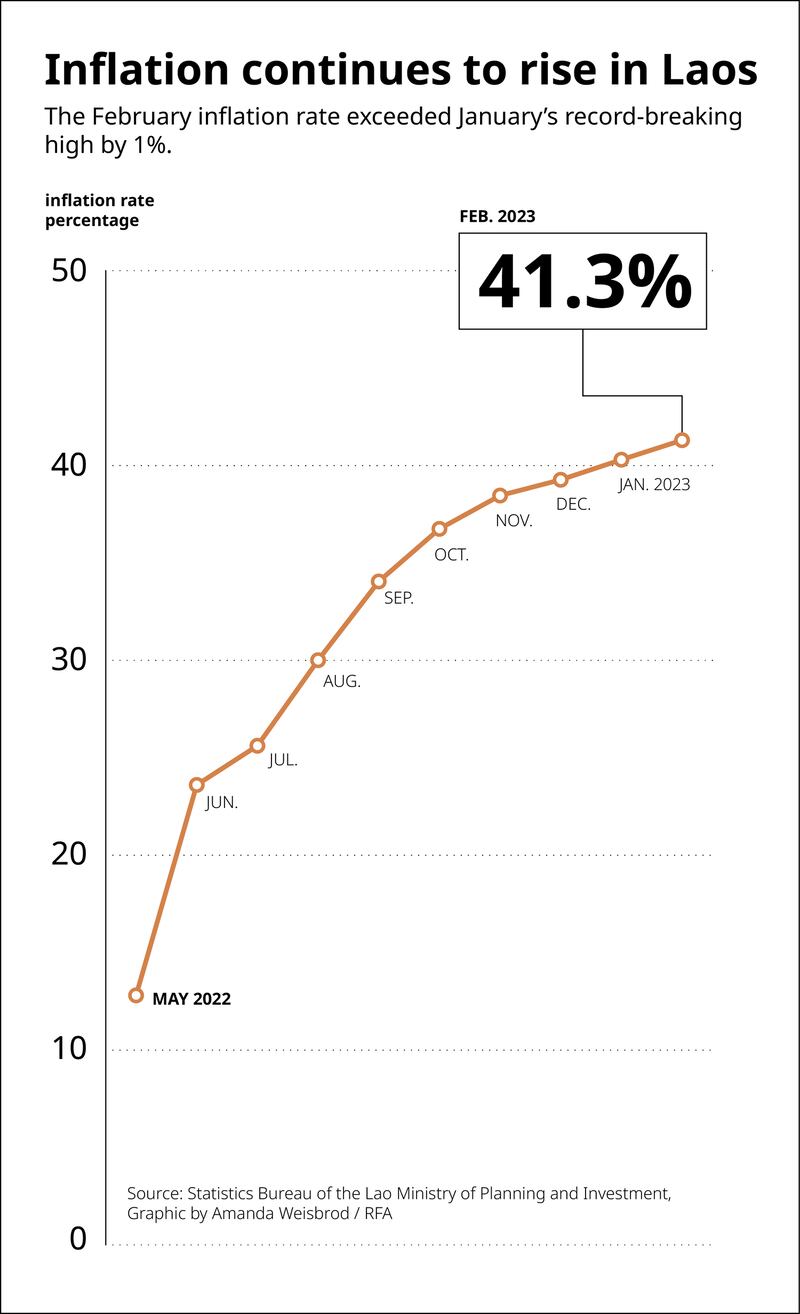

The inflation rate in Laos surged 41.3% in February, government figures show – a whopping jump from just a 2% rate the same time last year – despite drastic measures taken by authorities to tame the crisis.

The government has ordered import restrictions and the closure of all private money exchangers in the country, allowing only banks to exchange foreign currencies.

The soaring inflation has been driven by a depreciation in the Lao currency, the kip, and declines in foreign investment.

But some residents say the government’s new import limits have made the crisis worse since domestic industries don’t produce all the supplies needed for factories.

“Laos doesn’t have enough goods to produce by itself, so we have to import from Thailand,” said a resident in the capital Vientiane, speaking on condition of anonymity for security reasons like others in this report. “If prices in Thailand are up, prices in Laos are up too. If the Thai baht is up, the Lao kip is up too.”

Some merchants have been forced to raise prices, further exacerbating the crisis.

“One bottle of vegetable oil sells in my store for almost 40,000 kip (around US$2.35), and I get a profit of 2,000 kip (12 U.S. cents),” one merchant in Vientiane told RFA. “Our government has a one-party system - so we can only listen to what they decide and cannot go against it.”

Low-income earners and government employees – whose salaries have not kept up with the price gains – have been hit hardest.

“One kilogram of pork or beef is over 100,000 kip (US$5.90), they used to be between 80,000-90,000 kip (around US$4.70-$5.30).” said one villager in Savannakhet province.

In Luang Prabang, one Lao woman said that locally-grown vegetables and other goods are selling at somewhat of a stable price, but imported goods are more expensive. “Meat prices never go down because of limited supplies,” she said.

An official with the Asian Development Bank in Laos had previously said that the government “needs to pay more attention” to inflation and called for urgent measures to address the issue.

Translated by Sidney Khotpanya. Edited by Nawar Nemeh and Malcolm Foster.