Lao government orders closing down environmentally destructive Chinese banana farms, first reported in January in Bokeo province, are now in force in six other provinces in the Southeast Asian country, sources say.

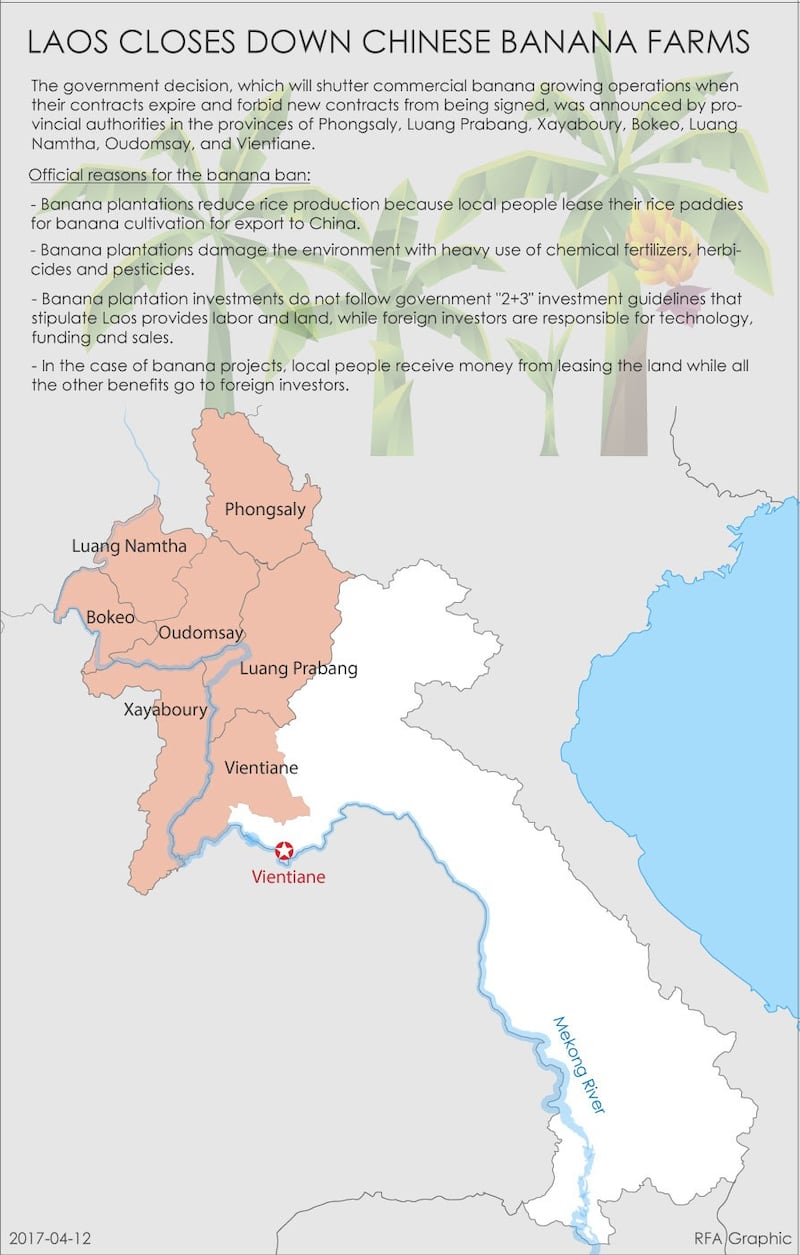

The ban, which will shutter the commercial operations when their contracts expire and forbid new contracts from being signed, was conveyed by provincial authorities in Phongsaly, Luang Prabang, Xayaboury, Bokeo, Luang Namtha, Oudomsay, and Vientiane, local sources confirmed to RFA’s Lao Service.

Chinese investors in Luang Prabang have now “gone quiet” since the ban went into effect at the beginning of this year, an agriculture and forestry official in the province told RFA.

“Many investors have now gone home, since they won’t be allowed to continue,” RFA’s source said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“Some are now planning to grow sugarcane instead of bananas, though, because sugarcane uses fewer of the chemical substances” needed for fertilizer and pest control, the source said.

Provincial authorities are now considering how to rehabilitate land contaminated by the heavily polluting plantations, an official of Phongsaly province’s natural resources and environment department told RFA.

“Authorities will not renew the investors’ contracts when those contracts expire, but will provide villagers with other occupations, because the banana plantations are damaging the environment and people’s lives,” the official said

Plantations are still in operation in the province’s Yot-Ou and Bountai districts, “but are expected to close down in 2018,” he said.

Alternative crops planned

Villagers in Luang Namtha’s Long district are now being encouraged to grow other crops, one district official said.

“There is chemical contamination here for sure, and it will take time to clean this up,” the official said, adding, “Planting sugarcane and cassava could be viable alternatives to working on the banana farms.”

Plantation workers in Luang Prabang’s Nam Bak district are meanwhile being asked by authorities to stop work immediately, even though some contracts remain in force, an official in the province said.

“Because of the negative impacts of chemical fertilizers and other substances, we would like villagers to stop work on the plantations and wait until the [investors’] contracts expire,” the official said.

The investors themselves will be allowed to operate their farms until the contracts expire, “but they will not be allowed to expand the area of their plantations or renew their contracts,” he said.

The contracts in Nam Bak will be valid for three more years, so that by 2020 the plantations will be shut down and the villagers can grow other crops, he said.

Illnesses and deaths have long been reported among Lao workers exposed to chemicals on the Chinese-owned farms, with many suffering open sores, headaches, and dizzy spells, sources told RFA in earlier reports.

Sixty-three percent of plantation workers in the country’s north reported falling ill over a six-month period, with 35 percent reporting illness during the same period in the country’s central and southern areas, according to a study last year by Laos’s National Agriculture and Forestry Institute.

Conditions for banana workers have been so bad that many plantation owners have allowed them to work on the plantations for only three years because of fears that they might die there, sources told RFA in 2016.

Reported and translated by Ounkeo Souksavanh for RFA’s Lao Service. Written in English by Richard Finney.