Thailand’s Supreme Administrative Court ruled in favor of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand’s controversial power purchase deal from a Lao dam on the Mekong River, ending a 10-year legal effort by river activists to halt the power deal over environmental and social concerns.

The court in Bangkok dismissed an appeal in a lawsuit launched in 2012 by the Thai Mekong People’s Network from Eight Provinces requesting the scrapping the agreement signed by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) to buy electricity from the Xayaburi Dam, Laos’ first Mekong River dam.

The members of the network argued that EGAT’s power purchase agreement (PPA) is causing significant damage to the livelihoods and environment of millions of Mekong River Basin residents. The case, which was dismissed by a lower court, argued that Thai agencies involved in the approval process had failed to follow proper procedures, including consultations with people affected by the dam.

The Thai Supreme Administrative Court rejected the concerns Wednesday.

“The signing of the power purchase agreement with the Xayaburi Dam had no clear and direct impact on the environment and people,” the court said.

“In addition, the defendants had followed and conducted the proper procedures, the Procedures for Notification, Prior Consultation and Agreement (PNPCA),” it said.

“Therefore, the court sees that the defendants have done their jobs and proved that they were not negligent.”

The plaintiffs in the case accepted the verdict in the landmark level effort to halt dams by targeting power buyers but many rejected the Thai court’s assertion that there was no impact.

The court argued that “the impact may be created by the Xayaburi Dam, but not by the power purchase agreement, although we argued that the PPA led to the construction of the Xayaburi Dam,” said Rattanamanee Polkla, the lawyer for the Thai Mekong People’s Network from Eight Provinces.

“Obviously, the court didn’t see it that way, the court sided with the lower administrative court who dismissed our case years ago,” she told reporters outside the court.

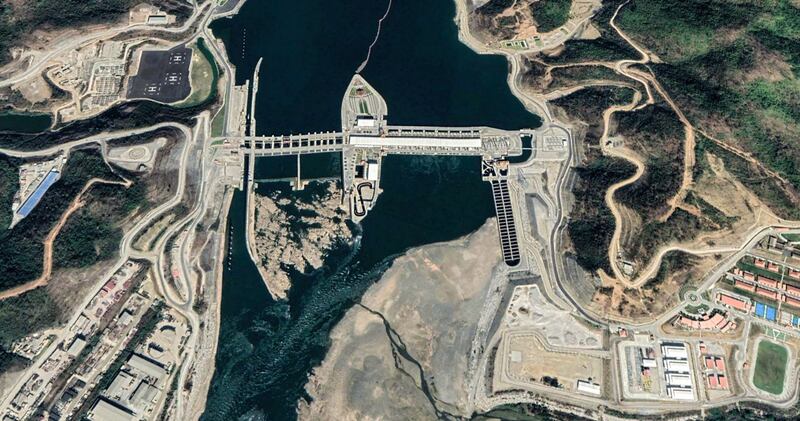

The Xayaburi Dam and the Don Sahong Dam, the first two of Laos' Mekong mainstream dams, were completed in 2020. Three others are in the planning or early construction stages as the government looks to generate revenue by selling the electricity from its hydropower projects to its neighbors, especially Thailand.

Despite serious environmental concerns and questions about the economic viability of the major dam buildup, Laos has at least 78 dams in operation in its rivers, including Mekong territories, and has signed memoranda of understanding for 246 other hydroelectric projects. China operates 11 mega-dams on the Mekong, with at least two more planned.

The Mekong is one of the world’s most biodiverse river basins with more than 1,100 species of fish. As the world’s largest inland fishery, the river is a vital food source for the 70 million people in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam who live in its basin.

'The impact is everywhere'

Mekong region residents say an unpredictable cycle of floods and droughts are the result of the many dams China and Laos have built upstream that siphon off water for agricultural and other uses. Experts say the dams make the impact of periodic droughts in the Mekong basin worse and rob the river of the "pulse effect" that spreads water and nutrients that support fisheries and farming.

“The impact is happening; the Mekong River is being destroyed; everybody is affected,” said Pianporn Deetes, Thailand Campaign Coordinator of the NGO International Rivers.

“We just want the Mekong River to continue to exist, our people to continue to live and our children continue to sustain their lives,” she said.

A villager who lives near the Mekong River in Thailand’s Loei province told RFA Lao there was no denying the impact on residents.

“We knew that our fight may fail, but we have no choice but continue to fight,” he said.

“The impact is everywhere. Look at the water: When it goes up, it goes up very quickly, we can’t do anything. All of our vegetables on the Mekong River bank are destroyed,” added the villager.

Plaintiff Ormboon Thipsuna, a Thai civil society activist from the Lower Mekong River Basin, said his group “accepted the court verdict and we’ve gained some more insight in our fight to protect our Mekong River” and would carry on.

“The decision shows us that we have another issue or another lawsuit to pursue; all we have to do is to gather more evidence and proofs of the problems and launch another fight again in the future,” he said.

But Chanchai Dajan, leader of fishermen from Khamphi village in Loei province, Thailand the ruling reflected disparities in power like “an elephant stepping on a little bird” that overlooked suffering on the ground.

“The court sees this case in an air-conditioned room. They didn’t come to the field,” he said.

“They should come down here and see what’s happening to the Mekong River and how the environment and the ecosystem are being ruined.”

Translated by Max Avary. Written by Paul Eckert.