The recent approval of plans by a Chinese-backed mining firm to explore a vast swathe of northwestern Myanmar for copper has alarmed residents who fear losing their farms in a repeat of earlier bitter clashes over land rights, pollution, and compensation that gripped the region.

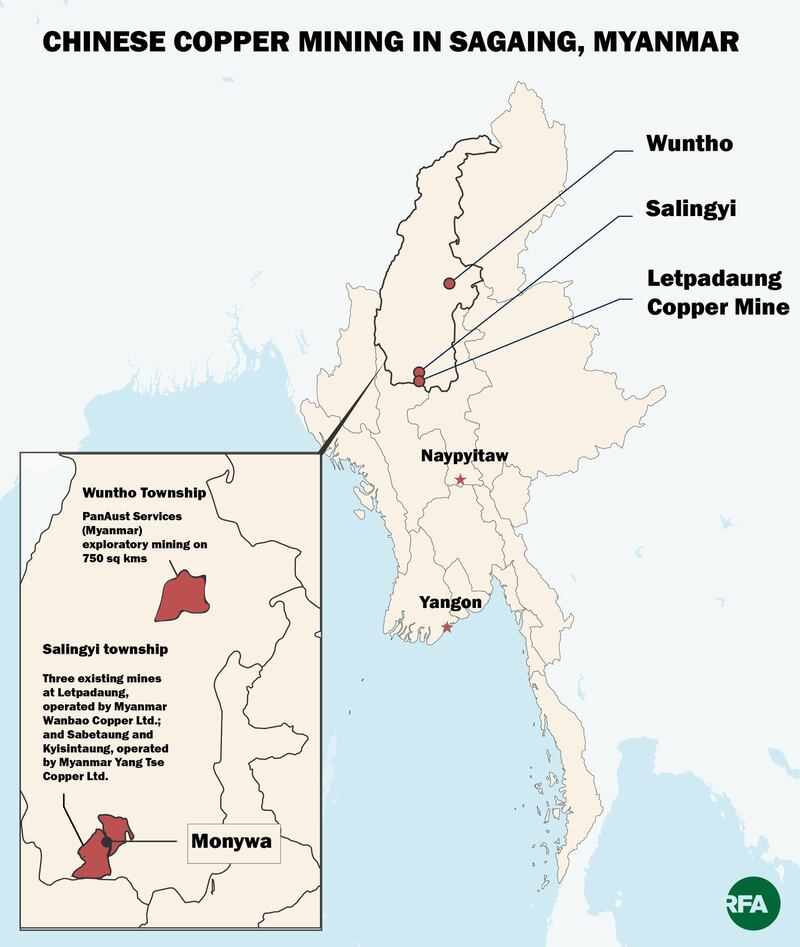

The multinational firm with links to a Chinese state-owned resource exploration company began initial operations early this year to explore 750 square kilometers (290 square miles) of land in the Sagaing region, home to Letpadaung — a name that symbolizes social unrest over Chinese copper mining after years of protest.

It is places like the Sagaing copper region where resource-rich Myanmar’s desire to develop an economy stymied by decades of isolationist military rule intersects with neighbor China’s ambition to connect regional and global economies to the Chinese market with a vast infrastructure-building scheme.

Local residents, however, say mining companies have a history of neglecting community concerns and causing environmental damage, while taking their farmland without adequately compensating them. Community conflicts with Chinese workers are not rare amid popular wariness about China’s growing influence.

Activists say that when making deals, the central government and foreign investors do not listen to local officials who have to deal with residents during the approval process, while officials at all levels are eager to create jobs. Myanmar exported about U.S. $825 million a year worth of copper in 2018, about half to China.

In the latest move to exploit the copper reserves of Sagaing, a mostly rural region of 5.3 million people that borders northeastern India, PanAust Services (Myanmar) Co. Ltd. was given a new five-year exploratory license in May to look for copper deposits in three townships in Sagaing region.

Since 2016, the firm has had exploratory rights to more than 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles), according to information on PanAust’s website.

PanAust is an Australian incorporated company owned by Guangdong Rising H.K. (Holding) Ltd., a wholly owned subsidiary of Guangdong Rising Assets Management Co. Ltd. (GRAM).

GRAM is a Chinese state-owned investment company active in mineral resource development, electronics, industrial waste management, real estate, and finance. In the division of labor among state-owned enterprises under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), GRAM’s role is to support resource development in Southeast Asia, researchers say.

Belt and Road in Myanmar

The BRI, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature global development initiative, includes major plans in Myanmar, such as the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, which features railways linking southwestern China’s landlocked provinces to a deep-sea port in Rakhine state on the Bay of Bengal.

In Myanmar, PanAust holds a 90 percent stake in Wuntho Resources Company Ltd. (WRCL) and has set up a joint venture with Myanmar Energy Resources Group International Company Ltd. (MERG), a Myanmar-based company which holds the remaining 10 percent of WRCL.

WRCL holds seven exploration licenses in Sagaing region.

If PanAust finds sufficient copper reserves during the next five years and the mining project is realized, the copper mine could take its place as a new mega-mining center next to the U.S. $1 billion Letpadaung copper mine project.

PanAust Executive Chairman Qun Yang welcomed the green light to expand explorations, saying the country was working in neighboring Laos and was well-placed to start exploring in Sagaing once the coronavirus pandemic conditions allowed.

“PanAust has made significant improvements to healthcare, education, and transportation infrastructure in the areas in which it operates,” he said in a statement.

Qun Yang said the project in Sagaing would “contribute to the nation’s long-term economic growth and prosperity, including through job creation.”

Letpadaung legacy

If comparisons to Letpadaung cause excitement among mining executives, the name evokes trouble to others in the Sagaing region, where mining began in the 1980s.

China’s Wanbao Mining Copper Ltd., which has operated the Letpadaung project in cooperation with the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (UMEHL) since 2010, plans to invest U.S. $1 billion at Letpadaung over 30 years.

For years, the Letpadaung project has generated heated disputes over land takeovers, prompting violent crackdowns on protests by farmers forcibly displaced by the chinese-run mine, who contend that they have not received fair compensation for their losses.

An incident in December 2014 left one woman dead and several people injured when police fired on protestors. And in February 2015, witnesses told RFA that police fired guns during a clash at Letpadaung.

A parliamentary inquiry commission on the Letpadaung project called for more transparency in Wanbao’s land appropriation process and urged the Chinese company to conduct environmental, social, and health impact assessments or to come up with an environmental management plan before the project continued.

Amnesty International and other rights groups have blasted authorities’ harsh treatment of protesters and called for the projected to be halted.

In May 2019, Myanmar’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation raised concerns over increased levels of particulates in the air near the project, and lawmakers complained about the high levels of sulfur dioxide and raised concerns about deforestation in the area, the analysis said.

Me Me Tun from Wuntho township, who said she heard that 22 villages in her community are in the exploration zone, cited Letpadaung as a reason why many residents do not want Chinese companies operating in their area.

“We don’t trust Chinese companies anywhere — on wildlands, on farmlands, or in villages,” she said.

“Who’s going to take responsibility if any damage is done? Look at what [happened] in the Letpadaung area,” Me Me Tun said.

“We heard the company said local residents agreed to it, but which local residents?” she asked. “We did not see any meetings with any local residents. We did not get any information.”

Corporate responsibility concerns

Than Zaw, who lives near the Wuntho project site, said Chinese companies doing business in Myanmar had poor reputations among local people and are not held to account for actions that harm communities.

“Most Chinese joint ventures exercise less corporate responsibility than do companies from other countries,” he told RFA.

“Most of the governments in the past stood by Chinese companies’ interests when conflicts occurred with local people. Nor did regional governments seek the support of locals in these cases,” Than Zaw added.

Zaw Lin Oo, a lawmaker representing Wuntho township, said that he and other regional legislators were not informed of the start of the exploratory project, though hundreds of acres have been allotted for mining operations.

He also said that concerned residents had asked him if their farmlands were included in the parcels covered by the exploratory licenses.

“We can’t tell them anything because we were not informed about the details of the project,” he told RFA, noting that other Chinese-run mining operations in Sagaing have caused several problems.

“Judging from past experience, local people are now almost certain that there will be similar problems in the region,” he said.

Min Min Oo, permanent secretary of Myanmar's Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, rejected the accusation that local lawmakers had not been informed.

PanAust had applied for and received permission from the Union government for the exploratory operations, and in 2018 the company took Sagaing regional lawmakers and delegates from the parliament’s Natural Resources Committee on tour of mining projects and briefed them about mining operations in Laos, he said.

Mine problems ‘never go away’

Thet Tin Nyunt, director general of the ministry's Department of Geological Survey and Mineral Exploration (DGSE), said PanAust began applying for permits in 2017, amended its application to meet new 2018 mineral regulations, and was approved by the Sagaing regional government and central government as of Feb. 21.

Than Hlaing, a lawmaker who represents Pinlebu township, also marked for exploration, said he will have no complaints against PanAust as long as the company conducts its operations in accordance with contract agreements.

“Currently, it is only doing exploration for metals, not mining operations,” he said.

“The company is digging holes deep into the ground to extract samples," he said. “I don’t find their operations damaging to the natural environment. We expect that they are sticking to the rules and regulations.”

The Myanmar government and PanAust say that the expanse of the project area will be reduced when the five-year exploratory period is completed.

“Despite the huge land area of the project, the actual mining activities will only be done at feasible sites so as to avoid local residents’ farmlands,” a PanAust official, who declined to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media, told RFA.

Tint Aung Soe, a member of the Myanmar Alliance for Transparency and Accountability, a civic group monitoring resource extraction in the country, said mining companies that receive direct permission from the central government usually ignore any problems that arise with local communities.

PanAust has not shared information with local residents or responded to their concerns about their farmland and the natural environment, he said.

“We don’t know what kind of activities it is doing or how well it is following rules and regulations,” Tint Aung Soe told RFA.

“We have seen that problems related to the loss of farmland from mining operations at the Sabae Taung and Kyay Sin Taung mountain ranges never go away,” he said, referring to long-running copper mine dispute in Monywa, another place in Sagaing, where a Wanbao affiliate fenced off village farmlands.

“The Union government should do more than give permission,” he said.

Reported by Aung Theinkha for RFA’s Myanmar Service. Translated by Ye Kaung Myint Maung and Kyaw Min Htun. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.