Violent political conflict since the February military coup and a deadly third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic have pummeled Myanmar’s economy, with the World Bank predicting a double-digit contraction of GDP this year and many urban residents struggling with shrinking incomes and rising food prices.

The military ouster of the country’s elected civilian-led government nearly six months ago came after a year of business and travel lockdowns to prevent the spread of the pandemic had hobbled the country’s $75 billion economy.

The Feb. 1 coup d’état brought widespread anti-military protests and walkouts by civil servants and white-collar workers that were met with military violence, killing more than 900 civilians.

Post-coup turmoil has disrupted critical services, including transportation, telecommunications, and public health and education — chaos that has hampered the fight against the third wave of the coronavirus and set the stage for worse economic hardship for Myanmar’s 54 million people.

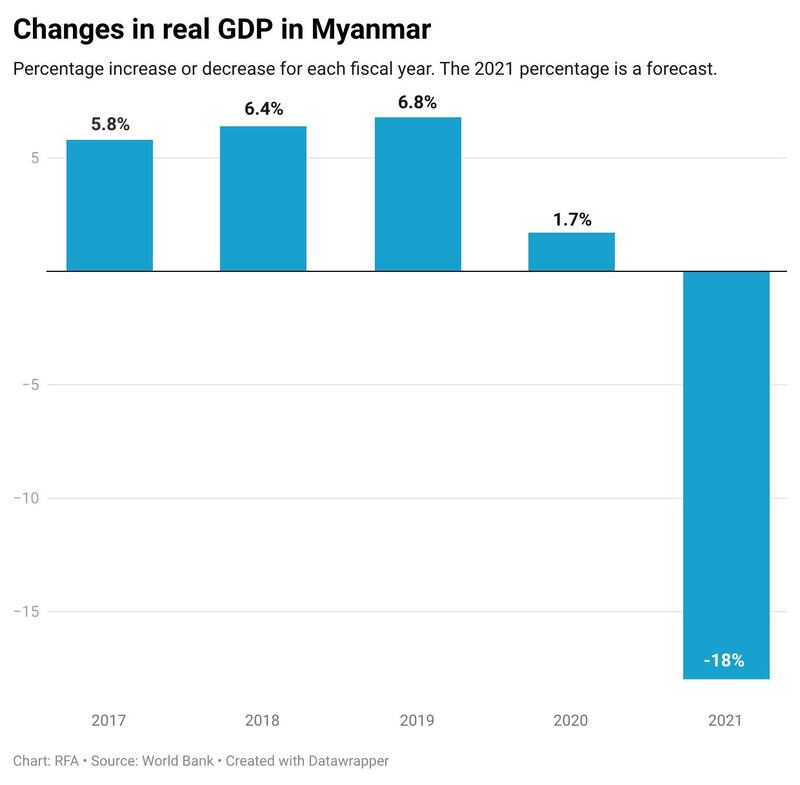

The World Bank, in an economic update published Monday, said Myanmar’s economy is expected to contract by about 18 percent in the current fiscal year (Oct. 2020-Sept. 2021), threatening to wipe out progress the country had made over the past decade of increasingly civilian rule that the coup has cut off.

Following weak economic growth in 2020, the new double-digit contraction would mean that Myanmar’s economy is about 30 percent smaller than it would have been without the COVID-19 pandemic and the military coup, with the number of people living in poverty likely to be double early 2019 levels by early next year, the World Bank’s “Myanmar Economic Monitor” said.

“The loss of jobs and income and heightened health and food security risks are compounding the welfare challenges faced by the poorest and most vulnerable, including those that were already hit hardest by the pandemic last year,” said Mariam Sherman, World Bank country director for Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, in a statement issued Monday.

For people in the Yangon region, the country’s most populous region with 6 million people, the bleak numbers translate into fewer jobs and lower income, higher food prices, and food insecurity.

“People have been in trouble since the first wave,” said San Myint Htay, a housewife in Dala township.

“Jobs have been scarce, and the coup has taken a turn for the worse. With rising unemployment in the country, rising commodity prices could lead to famine,” she told RFA’s Myanmar Service.

San Myint Htay said the price of staples like rice, sunflower cooking oil and eggs have nearly doubled.

Third wave has ‘compounded problems’

The World Bank report noted that Myanmar’s currency, the kyat, has depreciated by around 23 percent against the U.S. dollar between late January and July, leading to higher prices for imported goods, including fuel.

Nay Nwe from Yangon’s Thingangyun township, who lost her job after the coup, said many workers have been forced to leave their positions because of the closure of factories and many small local companies.

“After the coup, almost everyone became unemployed, and now COVID has become so powerful and is ravaging us really badly,” she said. “Many lives will be lost without money for emergencies.”

As of Wednesday, Myanmar recorded nearly 284,100 confirmed COVID-19 cases, including almost 5,000 new infections, and 8,210 deaths, including 365 new fatalities, according to data from the Ministry of Health and Sports.

Soe Tun, a Myanmar economist, said the economic downturn following the coup would get worse in the rest of this year as the pandemic takes its toll.

“COVID has really hit hard in the third wave,” which began in early July, he said. “There are so many infections. I think the next six months will be difficult because the third wave has compounded problems that arose after the current coup.”

When the contagious respiratory virus hit Myanmar in March 2020, it led to business closures and lockdowns that hit the country’s garment factories, tourism industry, and international trade. In addition, international sanctions have been imposed on military-owned businesses since the coup.

Economist Zaw Pe Win said the economy will not recover until next year if the current political instability continues.

“The economy is a part of politics, and if the political situation gets worse, the economy will only get worse,” he said. “Looking at things at present, politics here will not be good for the next one or two years. If the political situation is not good, the economy will not be good at all.”

A charity worker told RFA that despair and hunger can drive people to take drastic actions.

Last week in Yangon’s Thongwa township, a 50-year-old woman tried to jump off a bridge because she could not afford not afford food, medicine, or medical treatment for her ailing husband.

“She was standing on the bridge at Thongwa. We just happened to get to the spot when she was about to make the jump. We gently persuaded her and brought her back,” said May Ei Ei Phyo, an aid worker with the Thongwa Relief Society.

“She used to pick up trash with her husband, and now her husband is sick,” she said. “They have nothing. They have no food.”

Reported by Myanmar Service. Translated by Khin Maung Nyane. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.