As the 2023 chair of ASEAN, Indonesia must push Myanmar to end violence and restore democracy nearly two years after the Burmese generals overthrew an elected government, Human Rights Watch said Thursday in launching its worldwide annual report.

The New York-based watchdog group urged Indonesia and eight other members of the regional bloc to not support the Myanmar junta’s planned election this year until it releases political prisoners. Myanmar is one of ASEAN’s 10 members.

"As the chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 2023, Indonesia should promote new and stronger action to address widespread abuses by the military junta in Myanmar," HRW said in a news release accompanying the release of its World Report 2023.

HRW’s Asia director called on Indonesia to take action to hold the Myanmar junta accountable for its failure to implement a regional five-point consensus.

At an emergency summit in Jakarta in April 2021 and in the presence of the Burmese junta chief, ASEAN leaders adopted this plan that aimed to end post-coup bloodshed and turmoil as well as return Myanmar to a democratic path.

“Ending Myanmar’s litany of abuses requires action, not just words,” Elaine Pearson told reporters in Jakarta. “ASEAN should consider suspending the Myanmar junta for its repeated failure to uphold the bloc’s commitment to a people-oriented, people-centered ASEAN.”

A military coup in Myanmar ousted the government led by Burmese democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi on Feb. 1, 2021.

The five-point consensus called for an end to violence, constructive dialogue among all parties, mediation by a special ASEAN envoy, provisions of humanitarian assistance and a visit to Myanmar by an ASEAN delegation.

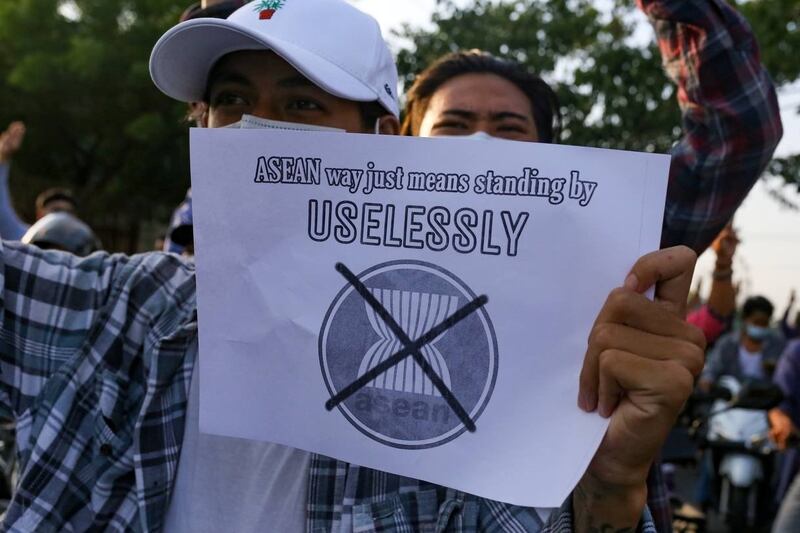

Indonesia and other ASEAN countries have expressed disappointment at the junta’s failure to implement the consensus, and human rights advocates and others have widely criticized the regional bloc for its collective weakness in pressing the junta in Naypyidaw to abide by the plan.

Regional observers and analysts, as well as the previous foreign minister of Malaysia, have said it was time to get rid of the consensus and devise a new plan that was time-bound and included enforcement mechanisms.

Despite such concerns, Indonesian President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo and Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, who met on Monday, said the five-point consensus was the best route to resolving the crisis in Myanmar.

Two days later, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi said her nation, as the holder of this year's ASEAN chair, was setting up a special envoy's office to deal with Myanmar under terms of the consensus.

“[I]ndonesia will make every effort to help Myanmar out of the political crisis,” she said. “Only through engagement with all stakeholders, can the 5PC [five-point consensus] mandate regarding facilitation for the creation of a national dialogue be carried out.”

On Thursday, Pearson called on ASEAN and the United Nations to not lend legitimacy to polls planned by the junta for this year, calling it a “charade” and “sham.”

“Indonesia should be working with a smaller group of like-minded governments to take concrete measures to stop the junta from violating the rights of its citizens and tell the junta that there will be no support for any election until all political prisoners are freed,” she said.

Since the coup, the Burmese junta has carried out a widespread campaign of torture, arbitrary arrests and attacks that target civilians, the United Nations and human rights groups have said. More than 2,700 people have been killed and more than 17,000 have been arrested in Myanmar, according to the Thailand-based Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

However, an analyst at Jenderal Soedirman University in Purwokerto, said Indonesia should ensure that the election proceeds because it could be the first step to a more durable peace in Myanmar.

“As the election is planned for August, the Indonesian government can still put more pressure on Myanmar,” Agus Haryanto told BenarNews.

‘Reconciliation isn’t working’

Along with allowing the vote to proceed, Indonesia should promote reconciliation in Myanmar, not just among the elite, but at the grassroots level as well, he said.

“We are seeing the influx of Rohingya refugees to Aceh. It’s an indication that reconciliation isn’t working in Myanmar,” he said.

Last week, Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said Rohingya arrivals at Aceh totaled 574 last year, adding that since 2020, 1,155 Rohingya have arrived in Aceh.

Amnesty International said the latest Rohingya arrival highlights the deteriorating situation in Myanmar following the military coup, as well as the dire conditions at refugee camps in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar district.

About 1 million Rohingya, including about 740,000 who fled Myanmar since a brutal military offensive in Rakhine began in August 2017, live in the crowded refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, a southeastern district by the Myanmar border.

Many of the stateless people have grown desperate because they see no hope of being repatriated to Myanmar, rights advocates and NGOs in the region have said. The Rohingya in Bangladesh cannot work or properly educate their children at these camps.

In 2022 alone, more than 2,000 Rohingya have taken to the sea in smugglers’ boats in the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, with nearly 200 reportedly people dying so far, UNHCR said.

Regional concerns

The HRW report also highlighted concerns about the state of human rights in other countries in South and Southeast Asia in 2022.

In Bangladesh, it noted increased attacks against political opposition party members, “raising concerns about violence and repression ahead of upcoming parliamentary elections.”

Human Rights Watch also alleged that the government had “increasingly targeted human rights organizations.”

It said a leaked government memo “appeared to show that the Finance Ministry and the Prime Minister’s Office were tasked in response to the U.S. sanctions with monitoring foreign funding to several human rights organizations,” referring to sanctions against the Rapid Action Battalion elite police unit.

In Malaysia, “police routinely torture suspects in custody with impunity,” HRW alleged.

It added that at least 20 people had died while detained in police custody last year.

The report said the government took “a major step backward on police accountability” by creating a “toothless” Independent Police Commission, which has limited powers to compel evidence be produced and cannot hold hearings.

In the Philippines, the climate for human rights has “hardly changed” following President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s inauguration in June.

Since taking office, the namesake son of the former longtime Filipino dictator and administration officials have tried to reassure international leaders that Marcos Jr. is committed to human rights and that the situation has improved.

“Human rights and civil society groups, however, debunked these claims with reports to the council of continuing human rights violations,” the report said, referring to the United Nations Human Rights Council.

In Thailand, where a government with deep ties to the military is still led by the ex-army chief who led a coup in 2014, HRW took Prayuth Chan-o-cha’s government to task over using a March 2020 emergency decree linked to the COVID-19 pandemic to crack down on demonstrators.

“[A]t least 1,469 people have been prosecuted under this draconian law – primarily for taking part in democracy protests. Police and prosecutors have leveled charges such as violating social distancing measures, curfew restrictions, and other disease control measures,” the report said.

It noted that most of the criminal complaints remained after the government lifted the decree on Oct. 1.

BenarNews is an RFA-affiliated news service