Residents of this community near where mass graves of trafficked migrants were discovered eight years ago say the border area is much quieter now – and they’re hoping it stays that way.

A decade ago, distressed foreigners on foot used to knock on doors asking for food. And city dwellers arrived by car from hundreds of kilometers away to buy smuggled goods for cheap at outposts just inside Malaysia.

But all that changed in 2015, after Malaysian authorities discovered more than 100 bodies –thought to be Rohingya and Bangladeshis – in two jungle locations in northern Perlis state, near a camp equipped with cages to lock up migrants.

After that, the authorities launched a crackdown on human smuggling and closed a free-flow zone on the border.

People living in Felcra Lubuk Sireh, a settlement within the boundaries of Wang Kelian that is eight km (five miles) from the Thai border, saw the effects of human smuggling up close and personal.

“I heard that these people came out from the woods near our village. They walked into the country through the Thai border via the beaten path in the jungle and someone would pick them up in four-wheel drive vehicles at the exit of the trails on our side,” Villager Yan Hashim said, adding that many of those who entered the country illegally brought children with them.

“They were unkempt, wearing ragged clothes, some without shoes and the majority appeared to be starving and some almost fainted because of exhaustion,” he said.

“Few could speak broken Malay while most used sign language to ask for water, food, slippers or clothes. It really broke our hearts to see them in that state and after the discovery, it occurred to us that the ones we encountered might be the same as those enduring the cruelties at the ... camp found on Wang Burma hill.”

Yan Hashim said fewer immigrants pass through the village today.

“No one knocks on my door asking for food anymore,” he told BenarNews. “It is better this way and I hope the free-flow zone will remain closed.”

The zone allowed Thais to travel to Wang Kelian and Malaysians to travel to Wang Prachan across the border without passports, distances of about 1 kilometer. Many Thais living on the other side of the border took advantage of this access and traveled to a petrol station so they could take fuel back to their homes, locals recalled.

“Before the free-flow zone was closed in 2015, this town was bustling with tourists coming from across the country including Kuala Lumpur just to shop for a variety of goods such as mattresses, kitchen utensils and clothes at cheaper prices. Many of them were willing to travel such a distance to set foot into Thailand without a passport,” said a 46-year-old trader who asked to be identified only as Kamal because of safety concerns.

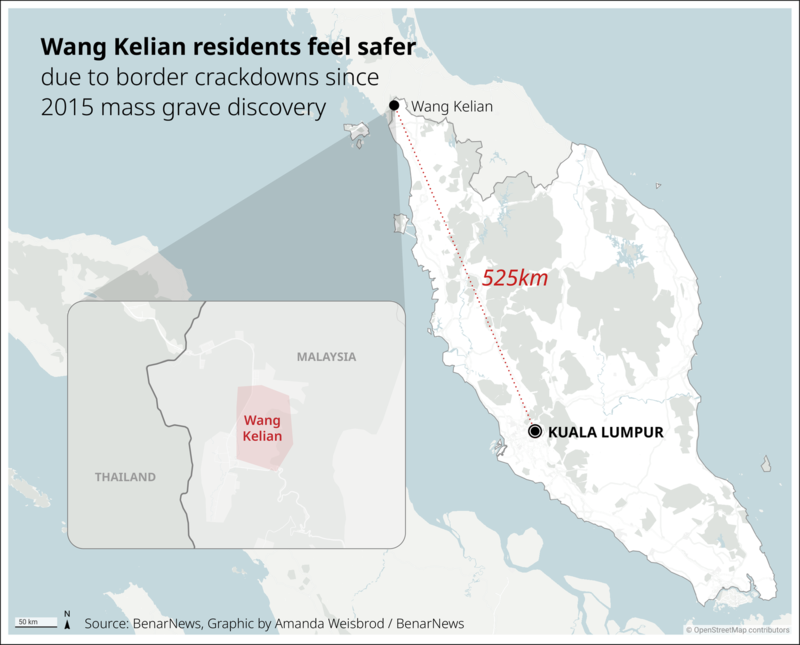

Today, residents said they feel safe as the cross-border smuggling activities and an influx of tourists, including those traveling 525 km (326 miles) from Kuala Lumpur, have slowed dramatically.

“It was lively then, but it came with a price,” Kamal said.

“Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against Thais as many of us are like family since we are neighbors, but it was unnerving when smuggling activities were happening at your left and right and even worse when there were ‘tonto’ (spies for smugglers) all around us.”

Kamal said he witnessed a Thai man loading subsidized cooking oil, which he purchased at the free flow zone and hid under his car’s seat before crossing the border unchecked where he could sell the packets at a profit.

Kamal said he did not report the incident to authorities over fears for himself and his family, noting that smuggling syndicates could retaliate.

Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution Ismail said the free-flow zone, introduced in 1993 and disbanded after the mass graves were discovered, was no longer suitable because of potential threats.

“For the time being, the ministry is focusing on the development of infrastructure in the border area before moving on to discussing reopening the free-flow zone further,” Saifuddin said.

“I am not saying that Wang Kelian is under threat, but I am referring to the potential danger to the country in general,” he said.

‘Right under our noses’

A government-commissioned panel in 2022 reported that Malaysian officials could have prevented the torture and deaths of the Rohingya and Bangladeshi victims found in the shallow graves seven years earlier.

An English-version of the report by the Royal Commission of Inquiry appeared briefly on its website before being taken down after the commission’s chairman told reporters it was completed in 2019 but was confidential and subject to the country’s Official Secrets Act.

A since-retired police official had filed a report in January 2015 that a villager had tipped him off about a trafficking syndicate having approached him and others to help transport people from the region.

On the first day of hearings on the tragedy, RCI members were told that personnel followed human tracks and a soapy stream to find a campsite with wooden fixtures resembling guard towers and a shop. An officer testified about hearing a generator at the camp near where the graves were found.

Previous reporting said the camp contained pens which likely were used as cages to keep the trafficking victims.

Since the discovery caught the world’s attention, the government has increased security in the area, including cutting off many trails used by the smugglers.

A police source who asked BenarNews for anonymity because of safety concerns, blamed the 2015 tragedy on integrity issues among border personnel from government agencies, unfenced border areas and a lack of security enforcement.

“This cruelty happened right under our noses. How could the personnel manning the area near the campsite in the state forest reserve fail to notice the loud sound generator used at the campsite at nights,” he asked.

“How did the majority of traffickers know which route to take to illegally enter the country, and 3 a.m. to 4 a.m. was the best time to sneak in unnoticed?

“Who alerted the traffickers or smugglers when authorities conducting operations or raids,” he asked.

Meanwhile, Mohd Mizan Mohammad Aslam, a professor at the National Defense University of Malaysia, said smuggling and trafficking could return on a smaller scale. He pointed to weaknesses in border fences that could allow smugglers to cut or climb over them.

“As long as the system is not revised or enhanced, the potential of border security being manipulated and abused persists especially with the post-pandemic predicament and demand for foreign workers in certain sectors,” he told BenarNews

“There is lots at stake with the ongoing smuggling activities, not only from security aspects but also economically as billions of ringgit are spent on subsidizing petrol, cooking oil and sugar to ease Malaysians’ burden. Those items can be smuggled out of the country and sold on the other side of the border.”