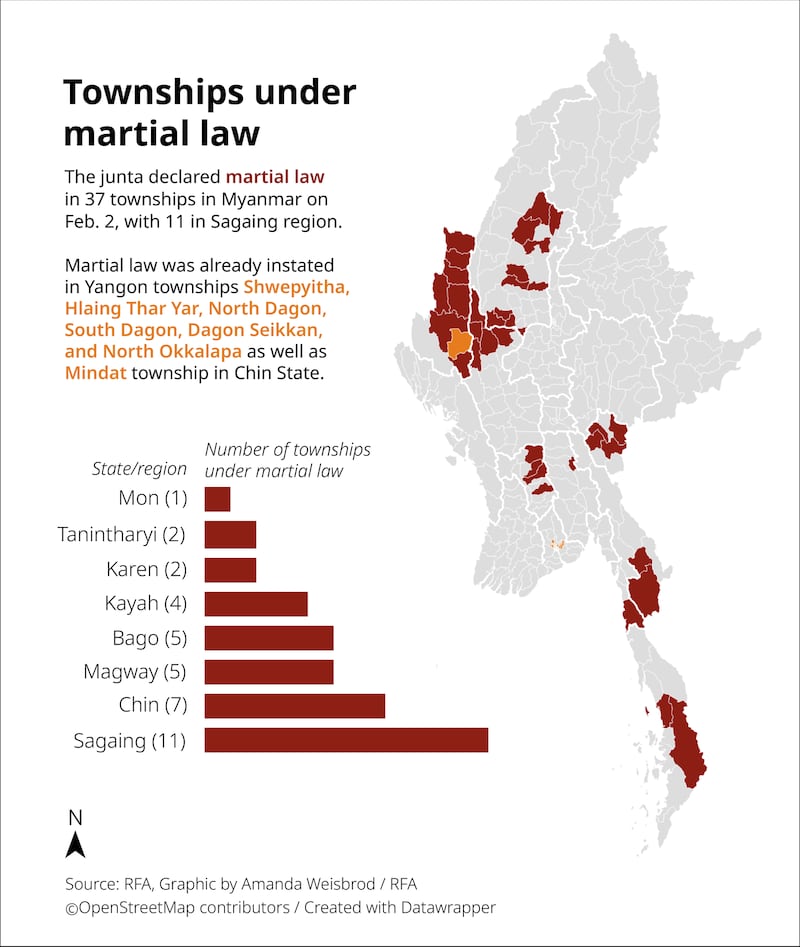

Myanmar’s military junta has declared martial law in 37 townships across the country and authorized military tribunals to hand down life sentences and the death penalty for a wide range of offenses, a move that political and military analysts say will lead to more bloodshed, displacement and terror.

Thursday’s move came a day after military leaders extended their emergency rule over the country for six more months. It marked the second anniversary of the Feb. 1, 2021, coup that ousted the democratically elected government.

All of the affected townships, scattered across eight states and regions, are in areas where anti-junta forces have a strong presence, from Sagaing in the north to Kayin in the south.

In fact, all the towns where martial law was declared are actually under control of forces opposed to the military government, said Defense Minister Yi Mon of the shadow National Unity Government, made up of members of the previous ruling party and other junta opponents.

“The military knows the actual situation – that they don’t control those areas but they declared martial law anyway just to save face,” he told RFA’s Burmese Service.

Still, martial law gives military commanders and military courts full judicial and administrative powers in those areas, allowing them to hand out the maximum penalty under the law for 23 specific crimes, including discrediting the state, illegal association, and unlawful possession of a weapon.

Giving military courts such power has no precedent in Myanmar, said a lawyer who requested anonymity for security reasons.

“As lawyers, we have never seen such an order issued,” the lawyer said. “Direction from the administration that the highest punishments must be imposed for these cases is not in accordance with the legal system that has been operating in Myanmar for generations nor international law.”

‘Like an ulcer that never heals’

Thein Tun Oo, executive director of Theyninga Institute for Strategic Studies, which is made up of former military officers, said that martial law had to be issued in order to crush rebel forces that have grown because the military had gone soft on them – a tacit acknowledgement that the military has faced serious setbacks.

“The military dealt with the armed resistance as softly as possible and avoided forceful attacks in some areas,” he said. “The military was giving them some time to think of peaceful ways in hope that they would join in on elections.

“But quite contrary to the military’s expectation, the resistance forces did not back down,” he said. “Armed resistance is like an ulcer that never heals as time passes. Now the martial law has been declared to crush them for the peace and security in those regions.”

Indeed, the 37 townships under martial law will likely be targeted for increased military hostility, said political analyst Than Soe Naing.

“Two years after the military coup, many people in several parts of Myanmar are going to fall into the hellhole of military aggression,” he said. “There will be no law or judicial court there. The military will attack, kill and commit genocide against our people in many ways.”

The move will essentially allow the junta to unlawfully kill armed resistance fighters in the region, said a military officer from the Khin-U Support Organization, one of the resistance groups in the northern Sagaing region, who like many in this article insisted on anonymity for security reasons.

“They declared martial law only to unjustly kill our revolutionary forces. What is feared is that they might kill more innocent civilians for no particular reason,” the officer said. “Our regional defense forces will just fight them head-on and then move to safety as usual. There is nothing to worry about.”

Elections not possible in these areas

The declaration also means that the junta is no longer capable of holding elections in those areas, Than Soe Naing said.

Junta chief Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing has pledged to hold multi-party elections, but opponents have dismissed those efforts as a sham because they believe any election will be rigged to exclude parties ousted by the coup and keep the junta in power.

Publicly, the junta has tried to minimize the resistance. Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing said in a Jan. 23 junta meeting that 198 of the 330 townships across the country were 100 percent peaceful, 67 had serious security issues, and 65 townships were in need of effective security measures.

And yet the junta has expanded martial law from six townships around Yangon to 37.

Zaw Yan, a farmers’ rights activist, said the declaration will “lead to major bloodshed.” It was made so that the military could “kill everyone in their way to rule those regions by hook or by crook.”

But it also shows that the junta is becoming desperate because the whole country is resisting it, he said.

The move will certainly boost the number of displaced people in the country, said security analyst Kyaw Saw Han. Already, fighting since the coup has uprooted at least 1.2 million people within the country, and many have also fled across borders into India or Thailand.

More arrests, killings and human rights violations are ahead, Kyaw Win, executive director of the London-based Burmese Human Rights Network said.

“According to martial law, they are going to act as judges, they are going to rule the cases in their favor openly in military courts,” he said. “They don't have the strength to fight all the resistance forces at the same time. Therefore, martial law was issued to help their forces cut the strength of the resistance.”

Translated by Myo Min Aung. Edited by Eugene Whong and Malcolm Foster.